Texas Paintings: The Surrender of Santa Anna (1886)

You can do nothing about the quality of Huddle’s work, but that does not diminish its importance to Texas history. –An Unknown Art Critic

Y’allogy is an 1836 percent purebred, open-range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is free of charge, but I’d be much obliged if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber. (Annual subscribers of $50 receive, upon request, a special gift: an autographed copy of my literary western, Blood Touching Blood.)

On the morning of April 22, 1836, Sion Record Bostick (sometimes spelled Bostwick) rolled out of his tent with orders to scout the San Jacinto battlefield. He was to accompany Joel Robinson and James A. Sylvester in tracking down and rounding up escaped Mexican soldados. Bostick was well suited for the task—a veteran of the battle of Gonzales, the siege of Béxar, and the battle of San Jacinto, fought the day before. Robinson, Sylvester, and Bostick were also charged, if possible, to ascertain what happened to General Antonio López de Santa Anna since his body had not found among the Mexican dead and he had not thus far been apprehended. With horses saddled, they went in search of Mexicans.

Sixty-four years later, on May 31, 1900, shortly before his death in 1902, Bostick dictated his recollection of what took place after he rode from the Texian camp on that April morning.

Capt. Moseley Baker told me on the morning of the 22nd to scout around on the prairie and see if I could find any escaping Mexicans. I went and fell in with two other scouts, one of whom was named Joel Robinson, and the other [James A.] Henry Sylvester. We had horses that we had captured from the Mexicans. When we were about eight miles from the battle field, about one o’clock, we saw the head and shoulders of a man above the tall sedge grass, walking through the prairie. As soon as we saw him we started towards him in a gallop. When he discovered us, he squatted in the grass; but we soon came to the place. As we rode up we aimed our guns at him and told him to surrender. He held up his hands, and spoke in Spanish, but I could not understand him. He was dressed like a common soldier with dingy looking white uniform. Under the uniform he had on a fine shirt. As we went back to camp the prisoner rode behind Robinson a while and then rode behind Sylvester. I was the youngest and smallest of the party and I would not agree to let him ride behind me. I wanted to shoot him. We did not know who he was. He was tolerably dark skinned, weighed about one hundred and forty-five pounds, and wore side whiskers. When we got to camp, the Mexican soldiers, then prisoners, saluted him and said, “el presidente.” We knew then that we had made a big haul. All three of us who had captured him were angry at ourselves for not killing him out on the prairie, to be consumed by the wolves and buzzards. We took him to General Houston, who was wounded and lying under big oak tree.1

John Forbes, who was present at the surrender of Santa Anna commented: “Through the whole General Santa Anna’s demeanor was dignified and soldierlike but a close observer could trace a Shade of sadness on his otherwise impassive countenance.”2

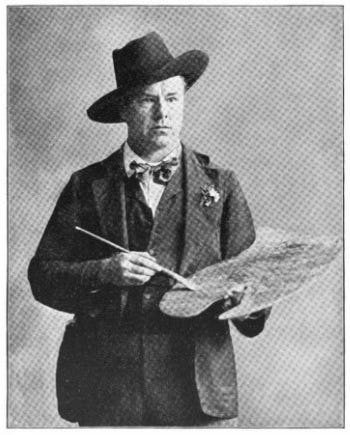

William Henry Huddle wasn’t present at the capture of Santa Anna but did capture his “impassive countenance” on a 72 x 114 inch oil on canvas painting. Born in Wytheville, Virginia on February 12, 1847, Huddle joined the Confederate cavalry when the Civil War broke over his hometown, serving under Joseph Wheeler and Nathan Bedford Forrest. At war’s end, in 1866, he moved to Paris, Texas with his family and worked in his father’s gunsmith shop. A few years later, in 1870, he moved to Tennessee to study portraiture with his cousin Flavius J. Fisher, a noted portraitist in Washington D.C. before the war. From there, Huddle moved to New York to study at the National Academy of Design, where he helped establish the Art Students’ League, along with Henry McArdle, who painted two depictions of the battle of San Jacinto—one in 1898 and another in 1901—and Robert Jenkins Onderdonk, who painted The Fall of the Alamo (1903) and fathered fellow artist Julian Onderdonk, who was famous for his bluebonnet paintings but also painted The Chili Queens at the Alamo (n.d.).

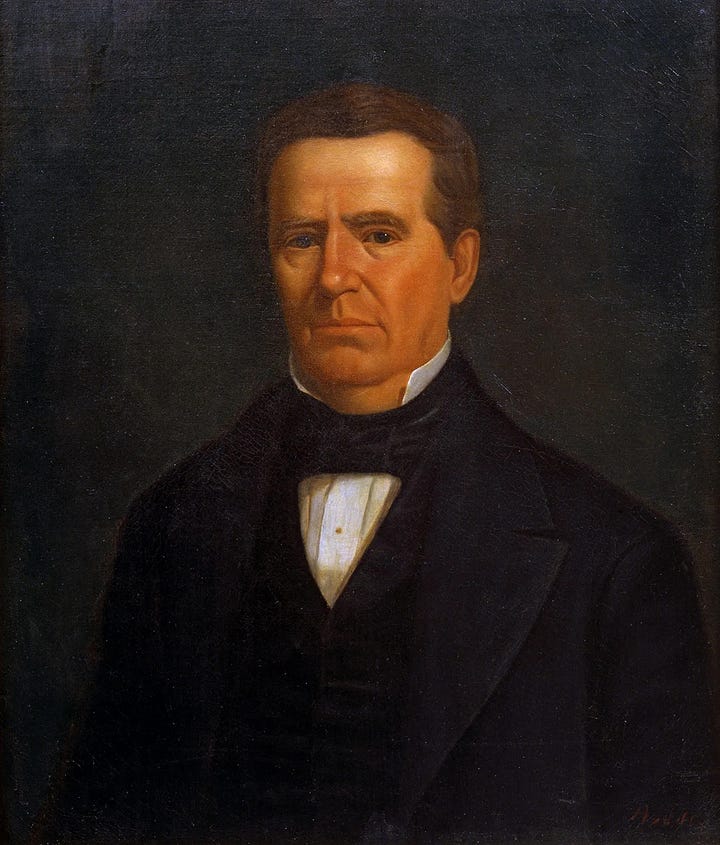

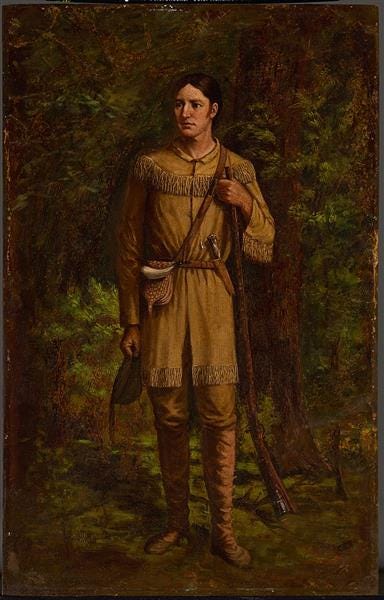

Huddle returned to Texas in 1876 and moved to Austin, where he taught at St. Mary’s Academy, but to improve his technique he studied for a year at the Bavarian Academy in Munich, Germany. Back in Texas, he focused his artistic energies on painting famous Texans and Texas historical events. Before his death in 1892, Huddle painted all the presidents of the Republic of Texas—Sam Houston, Mirabeau B. Lamar, and Anson Jones—and the first seventeen governors of the State of Texas. He also completed a painting of John Bell Hood’s Texas Brigade at the battle of the Wilderness, which was destroyed in the 1881 Capitol fire, a full length portrait of David Crockett (1889), and the painting he’s best known for: The Surrender of Santa Anna (1886), which commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the battle of San Jacinto.

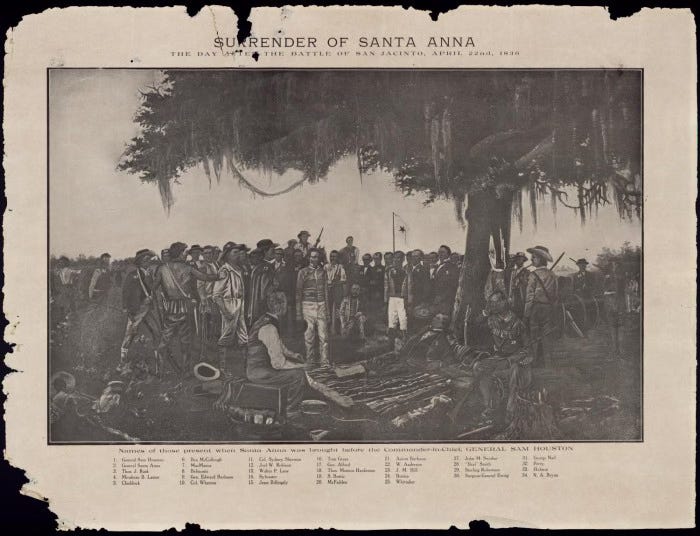

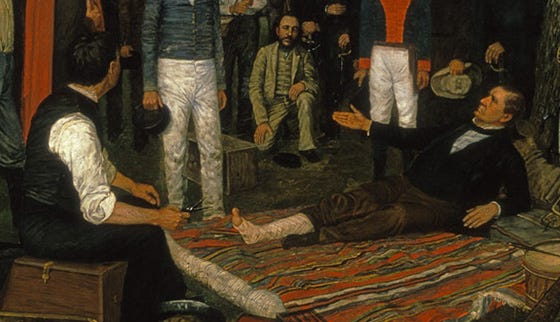

The Surrender of Santa Anna depicts the moment when the defeated and humiliated Mexican general is brought to an injured Sam Houston resting under an oak tree. Santa Anna, as Bostick testified, is wearing the white pants of a private. Houston is attended to by surgeon general Alexander Wray Ewing while Erastus “Deaf” Smith, sitting on a stump, with hand cupped to his ear, listens to the terms of surrender.

In preparation to tackle the historic scene, Huddle painted Study for the “Surrender of Santa Anna” (1885). Devoid of persons, this painting depicts a pastural scene. A large tree dominates the foreground and a dilapidated wooden fence commands the background. Huddle transferred the tree, along with its Spanish moss, to The Surrender of Santa Anna and replaced the fence with men who fought at the battle of San Jacinto.

At least thirty-four Texans in Huddle’s painting are identifiable. Besides Santa Anna, Sam Houston, Alexander Ewing, and “Deaf” Smith, other notable Texans include Thomas J. Rusk (secretary of war for the Republic of Texas), who stands behind Houston next to the tree in a black frock coat. Standing at Rusk’s right shoulder, wearing the same black coat, black cravat, and white shirt is Mirabeau B. Lamar, who at the time of the surrender had distinguished himself in battle by rescuing two surrounded Texians. Even Bostick makes an appearance.

Of the identifiable men, Huddle either painted them from life or from early daguerreotype photographs, which accounts for their aged faces rather than the faces of their younger selves in 1836.

Apart from the men of San Jacinto, Huddle also include two objects seeped in Texas lore. The famed “Twin Sisters,” a pair of cannons gifted to the Texian army from the citizens of Cincinnati, Ohio that saw action on April 21, 1836, are stationed on the far right of the canvas. In the background is what appears to be Joanna Troutman’s flag given to the volunteers of the Georgia Battalion who were massacred at Presidio la Bahía (in Goliad).

Some consider Troutman’s banner to be the first lone-star flag of Texas. It was made from a white silk dress with an appliquéd blue five-pointed lone star centered on each side. One side bore the slogan, “Texas and Liberty,” while the other side read, Ubi libertas habitat, ibi nostra patria est—“Where liberty dwells, there is my country.” When word reached Presidio la Bahía, on March 8, 1836, that Texas had declared independence from Mexico six days earlier Colonel James W. Fannin, commander at Goliad, ordered the Troutman flag raised over the garrison. Unfortunately, at sundown, while the flag was lowered it snagged on the halyard and was badly ripped. A few sorrowful shreds still blew on the breeze when the men of Goliad fled the fortifications on March 19—an ominous omen of what was to come eight days later.

Another flag of white cloth bearing a single blue star could easily be made, but the only known Texian flag to fly at the battle of San Jacinto was the one carried by Sergeant Jim Sylvester of Captain Sidney Sherman’s Kentucky Riflemen. This flag, known as the “Newport Rifle Company Battle Flag,” had been presented to Sherman and his men by the ladies of Newport, Kentucky. It featured a partially clad maiden, clutching a sword with a draped banner reading, “Liberty or Death.” The repaired original hangs in the Senate Chamber of the Texas State Capitol.3

Whether the flag in The Surrender of Santa Anna is there because of some faulty remembrance of a veteran Huddle interviewed, many of whom would have been in there seventies or eighties at the time he was painting, or there to remind viewers of Santa Anna’s cruelty and barbarism in ordering the massacre of more than three hundred men at Goliad, no white standard with a five-pointed blue star flew over the battlefield at San Jacinto.

When Huddle finished The Surrender of Santa Anna in 1886 it lingered in his studio for five years, until the Texas legislature purchased it from his family in 1891 for $4,000. Today it hangs in the South Foyer of the Texas State Capitol.

Sion R. Bostick, “Reminiscences of Sion R. Bostick,” The Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association, vol. 5, no. 2 (October 1901), 92–95, emphasis in original. Some details of Bostick’s account are disputed. They are outlined in the historical journal, but the general facts of his account are agreed upon.

John Forbes, “Surrender of Santa Anna,” Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

Stephen L. Moore, Eighteen Minutes: The Battle of San Jacinto and the Texas Independence Campaign (Dallas: Republic of Texas Press, 2004), 418. Robert Maberry Jr. argues there might have been a Lone Star and Stripes flag carried into battle at San Jacinto. See Texas Flags (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2001), 32.

Support Y’allogy—

Much obliged, y’all.

Deaf Smith is one of my most favorite Texas patriarchs. Love the Big Drunk too.