Texas Paintings: Chili Queens at the Alamo (n.d.)

Their nightly encampment upon the historic Alamo Plaza, in the heart of the city, had been a carnival, a saturnalia that was renowned throughout the land.

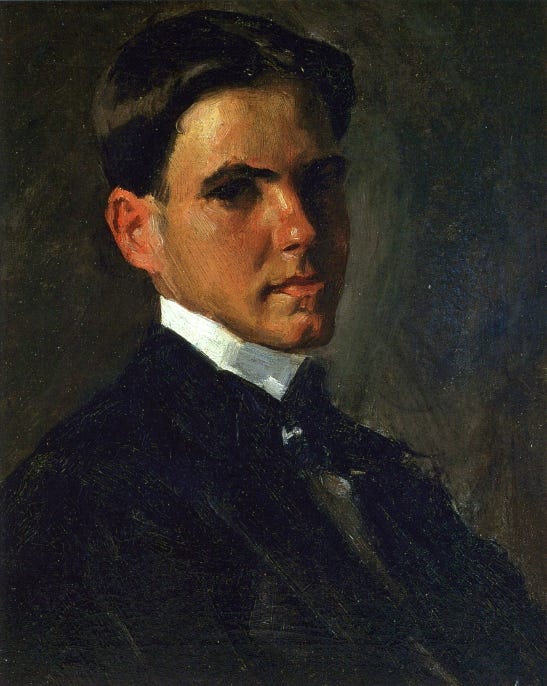

William Sydney Porter (O. Henry)

When William Sydney Porter (better known as O. Henry) penned the words describing the “nightly encampment” of the Chili Queens at “the historical Alamo Plaza” in his short story “The Enchanted Kiss,” he had been away from Texas for six years and out of a federal prison—for embezzling funds from an Austin bank—for three. But Porter knew of what he wrote. It wasn’t all imagination when it came to composing a pen portrait of “the coquettish señoritas” who served “strange piquant Mexican dishes . . . at a hundred competing tables, [and] crowds [thronging] the Alamo Plaza all night.” He had lived in Texas for sixteen years, from 1882 to 1898, with homes in Austin and San Antonio. He had, there is little doubt, sat at one of those tables peering through the rising steam from a bowl of chili and into the eyes of one of those coquettish señoritas.

Another who may have done as Porter did on some other San Antonio evening was Robert Julian Onderdonk. He too captured the Chili Queens in a portrait, though his medium wasn’t pen and paper, but brush and canvas.

Julian was born on July 30, 1882, in San Antonio to Robert and Emily Onderdonk. A native of Maryland, Robert had come to San Antonio in 1878, after studying at the National Gallery of Design in New York, under the tutelage of William Merritt Chase. He planned to linger in the Alamo City only long enough to earn passage to Europe. But those plans changed when he met Emily, a local girl. They married, raised a family, and Robert stayed for thirty-eight years. His most famous painting is about Texas’s most famous historical event: what he titled, The Fall of the Alamo. It depicts David Crockett in an historic pose, his hands over his head, swinging the butt of his musket at Mexican soldiers pouring into the doomed mission-fort.

Like his father, Julian became an artist. In the late 1890s, he attended West Texas Military Academy in San Antonio. To help pay tuition, he was admitted to the faculty to teach art. At the age of eighteen, in 1900, Julian began teaching art at Laurel Heights School. A year later, with a loan from San Antonio banker G. Bedell Moore, Julian moved to New York for formal training at the Art Students League. Eventually, he studied with American Impressionist William Chase, at the Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art in Southampton on Long Island.

Chase was taken with Julian’s talent. In 1901, shortly after Julian arrived in New York, Chase painted a portrait of the young artist. For Julian’s part, Chase became more than a teacher. He was a mentor and friend, as he had been to Julian’s father some twenty years before. Chase encouraged Julian’s talent as a landscape painter, in the impressionistic style—a style and subject that would make Julian famous as a Texas painter.

Though the cities differed, Julian’s outlook mirrored that of his father’s: he had no intentions of staying in New York. But like his father, he met a girl, Gertrude Shipman. They wed on June 18, 1902, and within a year gave birth to a daughter, Adrienne. New York was difficult for the young Onderdonk family. Julian briefly taught painting in his own school, Onderdonk School of Art, and managed to sell a number of canvases (under a pseudonym) to a department store with the help of businessman Charles E. Tunison. By 1909, however, he had had enough of the Big Apple.

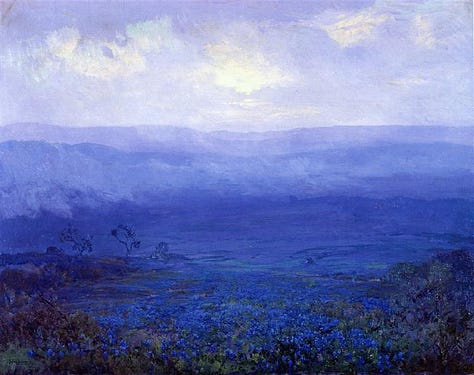

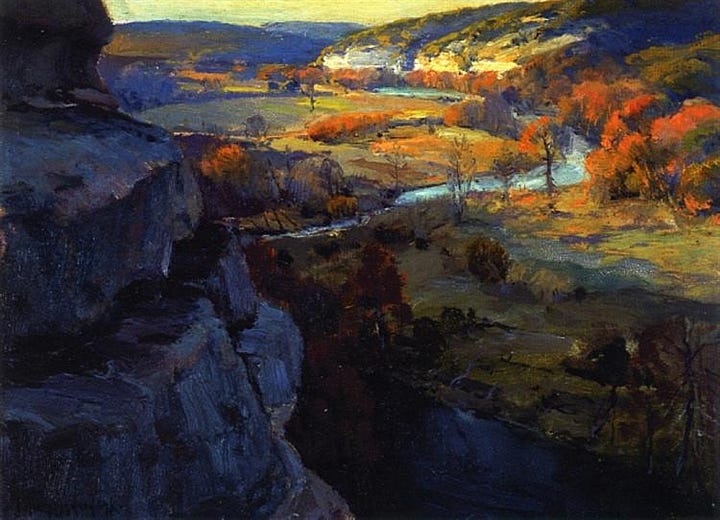

In November of that year, Julian moved his family to San Antonio. Before year’s end, Gertrude gave birth to their son Robert. It was in the surrounding countryside that Julian practiced and perfected the technique of en plein air, painting what would become his most famous subject: bluebonnets. The years between 1911 and 1922, in the Texas Hill Country, in the open air, among Texas’s wildflowers, proved to be the most productive years of Julian’s career. His most famous and marketable paintings included Spring Morning (1911), Bluebonnet Field (1912), Blue Bonnets in Texas (1913), Road to the Hills (1918), and Bluffs on the Guadalupe River (1921).

Julian’s career ended when on October 27, 1922, suffering from an intestinal obstruction and appendicitis, he died. He was forty-years old.

For all his fame as a landscape artist, bluebonnets in particular, Julian did, on occasion, paint other subjects. His most unusual—and the only known Alamo painting—is The Chili Queens at the Alamo. From the time of his return to San Antonio in 1909 until his death in 1922, the Chili Queens continued to reign supreme during the evenings in the plazas throughout the city, including Alamo Plaza.

On some wintery eventide, Julian set up his easel and canvas and captured a scene of daily life in San Antonio. It’s a simple story: a December moon rises over the Alamo, gently lighting the plaza below, while a Chili Queen serves patrons in sombreros. Her homestyle tables are set, decorated, and lit in a traditional manner with tablecloth, clay dishes, vases of paper flowers, and laundry lamps. Next to her is a steaming pot of chili. A little girl feeds a flock of birds. A man in red tends to his oxen, either having or about to have his dinner. A man in blue converses with others who have come to partake in the “delectable chili con carne . . . a compound full of singular savor and a fiery zest,” as O. Henry described the dish.

Two unusual features surround this small canvas, measuring no more than 12” x 16”. First, the painting is undated. Based on the attention to detail and the skillful hand that produced the Chili Queens at the Alamo, it’s assumed Julian painted this scene sometime after his return from New York in 1909 and not before his departure for New York in 1901. If that assumption is correct, when might have he created this canvas? The structure on the left edge provides a clue. In 1887, the Catholic Church, which owned the Alamo and the old two-story convento or Long Barrack, sold that building to Honoré Grenet, a French businessman. Monsieur Grenet added a two-story wrap-around porch and castle-like towers to the roof of the Long Barrack and opened a museum and general store. After his death in the 1880s, the building was sold to Hugo, Schmeltzer and Co., a wholesale grocery store that expanded into a general mercantile. Hugo and Schmeltzer removed some of the garish embellishments, but retained the wooden superstructure and porch.

The superstructure remained in place until 1910, when the façade was torn down, revealing the existing Long Barrack beneath. Not only does Julian’s painting not contain the wooden covering, but it clearly shows the two-stories of the Long Barrack. If you visit the Alamo today one of the first things you’ll notice is that the Long Barrack isn’t two stories, but is, in fact, one story. The second story was removed in 1913. So, while we can’t be precise in dating Chili Queens at the Alamo, Julian must have painting it sometime between 1910 and 1913, most likely in the winter since the moon’s position over the campanulate (gable, or “hump” as it’s known) is placed in the correct position.

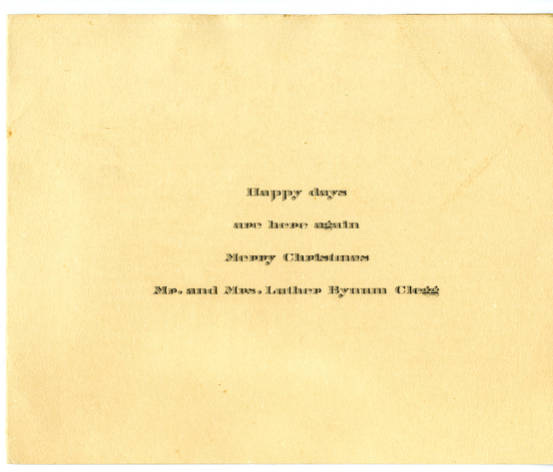

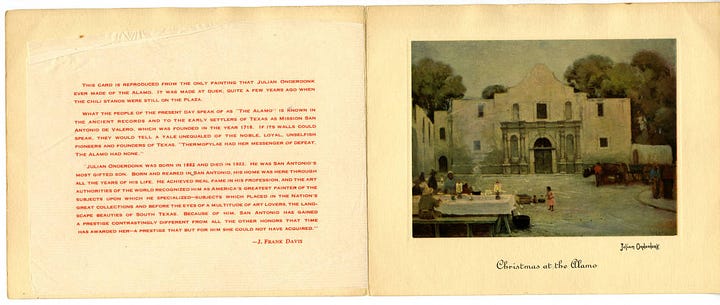

The second unusual fact about this paining, or more accurately not about the painting itself, but about a reproduction of the painting. The owners of the San Antonio Printing Company, Mr. and Mrs. Luther Bynum Clegg, used Chili Queens at the Alamo as their 1937 Christmas card. There’s nothing particularly noteworthy about this except their reproduction, titled Christmas at the Alamo, makes one striking omission: the moon is missing. No one believes the moon was added by a later hand into Julian’s original painting, so it appears the Clegg’s had it removed for their Christmas card. The reason why is a mystery.

Chili Queens at the Alamo hangs in the Witte Museum in San Antonio. But for a time if you wanted to see the original you had to have an invitation from the President of the United States. From 2001 to 2009, the painting hung in George W. Bush’s Oval Office, just to the left of the fireplace and above another Julian Onderdonk original, Cactus Flower.

The Clegg’s included in the Christmas card a statement from writer James Francis Davis praising Julian Onderdonk for the laurels he won for his hometown of San Antonio. Davis said,

Julian Onderdonk . . . San Antonio’s most gifted son. . . . He achieved real fame in his profession, and the art authorities of the world recognized him as America’s greatest painter of the subjects upon which he specialized—subjects which placed the nation’s great collections, and before the eyes of a multitude of art lovers the landscape beauties of South Texas. Because of him, San Antonio has gained a prestige contrastingly different from all the other honors that time has awarded her—a prestige that but for him she could not have acquired.

And that includes a small sample of what San Antonio used to be when the Chili Queens reigned in the Alamo City.

The piece you just read was 1836% pure Texas. If you enjoyed it I hope you’ll share it with your Texas-loving friends to let them know about Y’allogy.

As a one-horse operation, I depend on faithful and generous readers like you to support my endeavor to keep the people, places, and past of Texas alive.Consider becoming a subscriber. As a thank you, I’ll send you a free gift.

Find more Texas related topics on my Twitter page and a bit more about me on my website.

Dios y Tejas.