Texas Paintings: The Battle of San Jacinto (1901)

The most important find in Texas art in the last 100 years. In fact, it may be one of the best American finds, period, in the last century.

2010 Press Release, Heritage Auctions

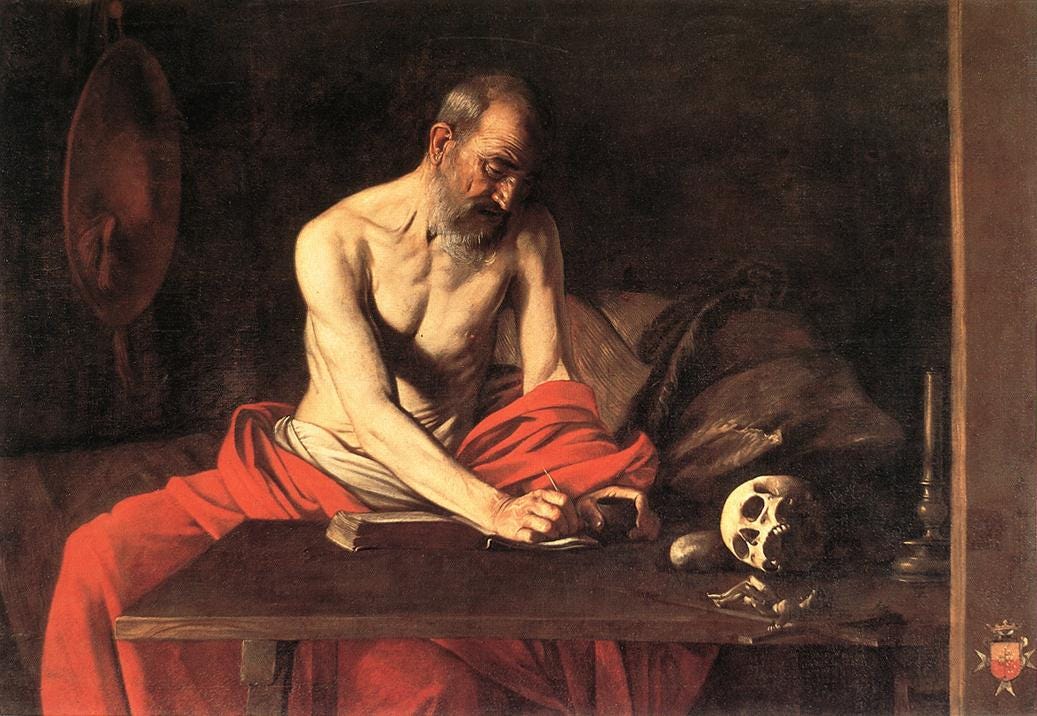

Not long ago I caught a documentary on the 1984 art heist of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s famous St. Jerome Writing (1607–1608) from St. John’s Co-Cathedral in Malta. In an effort to keep other patrons from the room that displayed the priceless painting, the thieves, after purchasing their tickets, put up a “Closed for Renovation” sign. Working quickly, the two thieves took the paining from the wall, cut the canvas from its frame, and threw the trussed up masterpiece out the museum’s second story window to an awaiting car below. The painting was eventually recovered, though damaged. It was discovered rolled up and stashed in a Malta warehouse with bolts of leather.

The fact that the St. Jerome Writing was retrieved was a minor miracle of detective work, given the fact that only 5 percent of stolen art is every recovered. Priceless works of art, like the St. Jerome Writing, generate worldwide coverage, preventing the outright sell of stolen works through legitimate channels following a heist. Stolen art usually meets one of four fates. It might be held for ransom, as was the case of the St. Jerome Writing. It might be traded on the black market for drugs, jewels, or arms, being passed around as “currency” in unsavory transactions. It might be stored until publicity about the theft dies down and then, years later, sold as a high quality replica, devaluing not only its financial but its cultural significance as well. Or it might simply be destroyed. Investigators estimate this is the case for 20 percent of all stolen art.

That leaves 75 percent of missing artworks unaccounted for, floating in the wind, including Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Man (1513–1514), taken during the Nazi invasion of Poland, and Caravaggio’s Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence (1609), stolen in 1969. The pieces from the 1990 break-in at Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston remain missing, including Rembrandt’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1633), Vermeer’s The Concert (1664), and Manet’s Chez Tortoni (1875). More recent thefts involve the disappearance of Cézanne’s View of Auvers-sur-Oise (1879–1880), stolen in 2000, and Van Gogh’s Poppy Flowers (1887), looted in 2020. These join missing works from Matisse, Monet, Gauguin, and Picasso.

Theft isn’t the only means of removing human genius from our cultural enrichment. Warfare, terrorism, natural disasters, and fires have all taken their toil. In an earlier article I mentioned how Lee at the Wilderness (1872) and Dawn at the Alamo (1875) were consumed in the 1881 Texas Capitol fire. While these paintings from Henry Arthur McArdle aren’t considered masterpieces, or even well-known outside of Texas historical and artistic circles, their destruction is a loss to our collective understanding of human achievement and history.

Another McArdle painting thought to be devoured by flames was his alternative version of The Battle of San Jacinto (1901). Commissioned by Texas historian James T. DeShields, the painting was publicly showcased only once, having been photographed at a 1909 state library exhibit. DeShields’s home burned in 1918, taking the 1901 painting with it.

Or so it was believed.

Howdy, y’all. Welcome to Y’allogy. Pull up a chair and put your boots up.

Before going on to enjoy a few more minutes of pure Texas goodness, I’d be obliged if you’d consider becoming either a free or paid subscriber—if you’re not already one. If you sign up as a free subscriber I’ll send you a baker’s dozen of my favorite Texas quotations. If you sign up as a paid subscriber, or upgrade to paid, I’ll send you the same baker’s dozen of Texas quotations, as well as a chili recipe from the original Chili Queens of San Antonio. Either way, I appreciate your consideration.

Half a country a way and ninety-two years later, in 2010, Jon Buell was visiting his grandmother, Elizebeth Bland, at her home in Weston, West Virginia. He went into the attic to explore and discovered, tucked away in a corner, a grime-covered painting. Intrigued by his find, Buell asked his grandmother about it. She didn’t recall any particular connection with the painting, except that it had been stored in the attic since the 1930s.

Buell wiped away what he could and took to the Internet. He was stunned by what he chanced on. The painting, which measured five feet by seven feet, bore a striking resemblance to the center scene of a much larger work—McArdle’s 1898 version of The Battle of San Jacinto. Buell sent photos of his painting to art museums throughout Texas. None showed much interest—until he contacted Atlee Phillips, director of Texas art at Heritage Auctions. But since Texas art scholars believed the original 1901 version was destroyed in the DeShields fire of 1918, Phillips was faced with a difficulty: how to authenticate the Buell find.

When the painting arrived in Dallas, two conservators took on the task of verifying the piece and cleaning it if it proved to be an original McArdle. Comparing the Buell discovery with the known 1898 painting, the smaller canvas did indeed bear a noticeable similarity with the earlier genuine. The composition of the action is painted in a classic “heroic” triangle shape, drawing the eye upward. McArdle used this technique in composing Lee at the Wilderness. In both the 1898 and 1901 paintings of San Jacinto the most arresting action involves the gold-fringed Sherman flag, portraying Lady Liberty against a blue background. The “sides” and “bottom” of the triangle are made up of the same cast of characters in both works: Sam Houston, General Manuel Fernandez Castrillón, an unidentified rifle-wielding Texian, and John Sylvester holding the Sherman standard. Edward Burleson, firing his pistol on his rearing horse, is in the same position in both painting, as is José Antonio Menchaca, and Andrew Briscoe, who looks out at the viewer in both works.

Nevertheless, there are differences. The most obvious is an omission: Santa Anna isn’t portrayed in the 1901 version. The other major deviation concerns the placement of Deaf Smith and the killing of Don Esteban Mora, as well as the struggle between Henry Kerns and Colonel Antonio Trevino over the Mexican national flag. In the larger 1898 version both actions are on the far right, away from the main engagement portrayed in the heroic triangle. But the size of the 1901 canvas accounts for this bunching action. Smaller, but notable, exceptions between the two versions include Rusk’s gray horse (1901) compared to his sorrel horse (1898), Briscoe’s (apparent) hatted brunette head (1901) in contrast to his hatless blonde head (1898), and Houston’s brown planter’s hat (1901) instead of a white planter’s hat (1898)—as well as the shift in his position from Sylvester’s right (1989) to Sylvester’s left (1901).

The experts didn’t believe these issues disproved the genuineness of the 1901 version, particular since the faces in both paintings are near identical, which would be expected for an authentic McArdle, who retained his notebook used to created the 1898 painting.

But this didn’t mean the conservators could declare the 1901 painting authentic. At least not yet. They took infrared photos to see below the surface paint. They discovered the Sherman flag showed up as a white ghost image to the right of its final placement. If you look carefully at the rifle-wielding Texian in the middle of the painting, just to the right of Houston, you’ll see a ghost rifle slightly elevated over its final position. The ghost images reveal the artist’s creative process in real time, rarely reproduced by counterfeiters and pointing to a legitimate work of art.

Taken together, this was enough to declare the 1901 painting as a bona fide McArdle. But there was one more wrinkle to authenticate the painting: Buell is the artist’s great-great grandson.

Questions remained, however. If DeShields commissioned the painting did he sell it or give it away before his home burned in 1918? And if he commissioned it in Texas, how did it end up in West Virginia? More to the point, how did it end up in the attic of one of artist’s relatives?

There are two answers for these questions. Both rely on the (logical) theory that McArdle never delivered the painting to DeShields because, it’s assumed, DeShields failed to pay the $400 commissioning price. So, McArdle kept the painting. But here’s were the stories diverge. Buell believes McArdle gave the painting to his son John Ruskin, who took it to Washington D.C. when he became secretary to Congressman Albert Sidney Burleson. Ruskin stayed in the D.C. area, later appointed U.S. Senate Librarian for the 77th Congress (1941–1943), until he retired to West Virginia. The other story involves McArdle’s second wife, Isis. After McArdle’s death in San Antonio in 1908, Isis returned to her native home of West Virginia, taking the 1901 version of The Battle of San Jacinto with her.

How it ended up in the Bland family home is simply a matter of genealogy. Whether Ruskin or Isis brought the painting from Texas to West Virginia is immaterial. It obviously ended up in the hands of Marie McArdle Bland—Isis’s daughter and Ruskin’s sister. She married George Linn Bland (1914) and gave birth to George Linn Bland Jr. (1917). George Jr. married Elizabeth—Buell’s grandparents—and gave birth to Linn M. Buell, Jon’s mother.

And that’s how a presumable destroyed work of Texas art went “missing” for more than a century and ended up in an attic of a small-town home in West Virginia.

Post Script: Buell was asked how much he thought his great-great grandfather’s painting was worth. He estimated its value somewhere between $10,000 and $20,000. On November 20, 2010, The Battle of San Jacinto (1901) was sold at auction by Heritage Auctions to an anonymous private collector for $334,600.