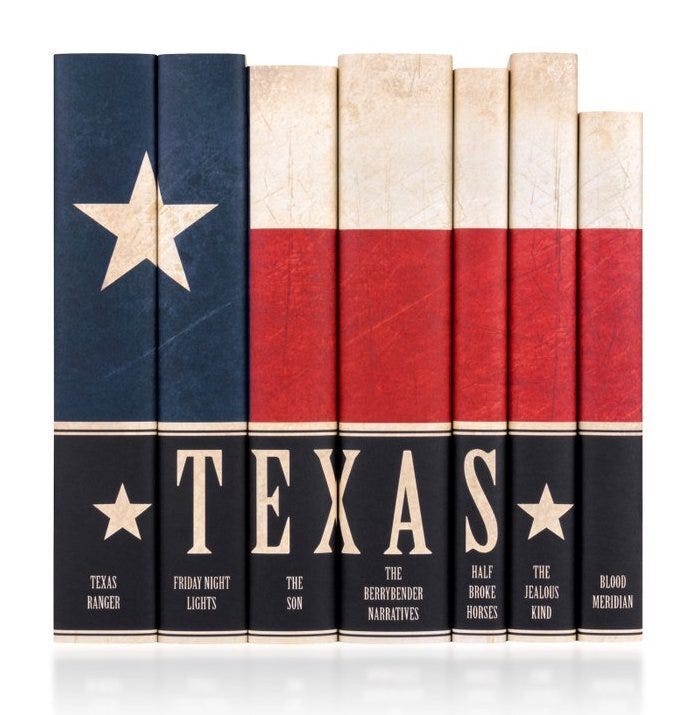

Texas Essentials: Books

One moderately good writer was all that was expected of a place like Texas.

Larry McMurtry

Texas is famous for many things, the Alamo, the Lone Star flag, cattle and cowboys, oil and gas, and our attitude—big, brash, and bold. But Texas isn’t known for its literary prowess. While any number of celebrated singers, songwriters, musicians, and movie stars have Lone Star roots, to date, Texas has really only produced two famous writers: Katherine Anne Porter (Indian Creek) and Larry McMurtry (Archer City).1

Primarily known for her short stories, Porter is an exceptionally fine writer. Don Graham calls her “The best writer Texas has produced.” Though most of her work isn’t Texcentric two of her short stories (“Noon Wine” and “The Grave”) and one novella (“Old Mortality”) are set in the heart of Texas. The majority of McMurtry’s work, on the other hand, is centered in Texas. He is our most famous writer, though he downplays his celebrity by describing himself as a moderately successful regional writer. And while he hasn’t reached the highest of a Twain, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, or Steinbeck he is unquestionably more than a moderately successful regional writer.

Why Texas has not produced more celebrated writers, whether of fiction or nonfiction, is hard to figure since we have no shortage of colorful and interesting characters and sayings. According to McMurtry it’s because “One moderately good writer was all that was expected of a place like Texas.”

Whatever the reason, Texas is still rich in written work. I consider the following books quintessential to Texas, not because they are all well written but because they all reveal something distinctive about the heart and soul of the Lone Star state and the people who populate it. Because these volumes vary across different genres, I present them according to publication date rather than in a sort of “Top Ten List.”2

The Log of a Cowboy: A Narrative of the Old Trail Days, Andy Adams (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1903)

Adams made it to Texas from his native Georgia at a time and at an age for him to help create one of the most enduring Texas and American myths—that of the cowboy. Though Charles Siringo’s A Texas Cow Boy: Fifteen Years on the Hurricane Deck of a Spanish Pony predates Adams’s book by eighteen years and Teddy “Blue” Abbott’s We Pointed Them North is the most famous of the cowboy narratives, Adams’s work is not only better written but offers unique insights into what it was like to cowboy in Texas during those mythical days when the range was open from here to Montana.

The Raven: A Biography of Sam Houston, Marquis James (Halcyon House, 1929)

James gives us one of the first complete pictures of the hero of San Jacinto, who dedicated his life to the safety, liberty, and prosperity of Texas. No one who wants to understand the history and character of the Lone Star state can do so without understanding the history and character of one if its greatest men.

Charles Goodnight: Cowman and Plainsman, J. Evertts Haley (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1936)

Along with Oliver Loving, Goodnight blazed the first commercially successful cattle trail from Texas to northern markets desiring beef. Both he and Loving, and their friendship/partnership, became the models for Woodrow F. Call and Augustus “Gus” McCrea in Larry McMurtry’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Lonesome Dove. Hailey’s biography is the definitive work on the man who served as a Texas Ranger, scout, cowman, innovative cattle breeder, and savior of the buffalo. You can’t get much more Texan than Charley Goodnight.

The Longhorns, J. Frank Dobie (Little, Brown and Company, 1941)

Three icons establish the character of Texas in the minds of outsiders: the Alamo, cowboys, and the longhorn. No breed of cattle is so steeped in history nor so identifiable to a region or state than are Texas longhorns. Dobie tracks the history and legend of these iconic animals before they were replaced by more delicate breeds that produced better yield per pound (and better taste) but lacked the Texas traits of toughness and independence.

Giant, Edna Ferber (Doubleday and Company, 1952)

Ferber’s novel of the Benedict clan and the Reata Ranch is melodramatic and hardly seems true to life, not unlike the movie produced from it. The novel was panned by many in Texas when it was published. However, it offers an accurate picture of how Texans think about Texas and about themselves—as big and bold, with a devotion to the Lone Star that is near fanatical. My wife’s grandmother, a former president of The Daughters of the Republic of Texas, told me when I joined the family: “Never forget, you’re a Texan first and an American second.” She would have fit perfectly as one of Ferber’s characters. Giant is not only important for these reasons, but also because it gives an unvarnished look at the relationship between Anglo-Texans and Tajanos, who for too long have been seen and treated as second-class citizens.

The Searchers, Alan Le May (Harper & Brothers, 1954)

As happens with many novels that become movies, the film, in the mind of the public, eclipses the novel it was based on. That is certainly the case with Le May’s book about the years long search for a girl taken captive by Comanches. The John Ford/John Wayne depiction is more famous than the novel, but both the film and book captured a few central traits Texans have always prided themselves on: bulldogged tenacity, personal courage, and an intolerance of violence perpetrated against another, which fits John Steinbeck famous observation, “To attack one Texan is to draw fire from all Texans.”

Goodbye to a River, John Graves (The Curtis Publishing Company, 1959)

Grave’s narrative is about one of the great rivers of Texas—at least as great as we have. In the late 1950s Graves learned the Brazos River would be damned for both flood control and the production of electro-hydraulic energy. Before that happened he decided to canoe the river while it remained wild and free. His narrative captures his three-week trip with remembrances of days gone by when settlers lived in terror of raiding bands of Comanches and Kiowa.

In a Narrow Grave: Essay on Texas, Larry McMurtry (Encino Press, 1968)

In the forward of McMurtry’s collection of essays he writes, “I might say at the outset that in criticizing Texas I have not been unaware that there are other states to which the same criticisms might apply. If so, that’s dandy. I am sure there are potatoes in Nebraska, but Nebraska is not my rooting ground.” Those who have read McMurtry for any length of time, especially his essays, knows he has a love/hate affair with his native land. In this early collection he demythologizes many of the pretensions Texans possess. This is not altogether wrong. And if anyone is going to do it, Texans will only listen to a fellow Texan give it to us with the bark off.

The Time It Never Rained, Elmer Kelton (Doubleday Books, 1973; republished by TCU Press, 1984)

Though not as famous as McMurtry, at least not outside the state, Kelton is one of the most prolific writers Texas has produced, with more than eighty works of fiction and non-fiction to his name. A multiple Spur Award-winner, as well as other literary awards, he was the longstanding editor of the Livestock Weekly. As a Texas novelists, The Time It Never Rained is one of his best. Perhaps no other book of fiction (or non-fiction for that matter) so intimately captures the plight of small town ranchers (and farmers) who are at the mercy of the weather. We joke that if you don’t like the weather in Texas, give it a few minutes and it will change—and change drastically. In urban areas talk of the weather is only discussed in terms of convenience or inconvenience; about whether the weekend will be beautiful or washed out, whether you ought to carry an umbrella today, or how hot it will be—hot as grandma’s kitchen or hot as hell’s kitchen. In rural parts of Texas, however, conversations about the weather can be a matter of life of death—or at least boom or bust for your current crop or cattle futures. Kelton painfully captures the results of what happens when the weather turns dangerous and brings along years long droughts. An experience not uncommon in Texas, even if it isn’t felt in places like Dallas, Austin, or Houston.

Lonesome Dove, Larry McMurtry (Simon and Schuster, 1985)

This is the quintessential Texas novel, pure and simple. Period. End of discussion.

Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Nation Tribe in American History, S.C. Gwynne (Scribner, 2010)

The Mexican government allowed Anglo immigration into their northern state of Tejas for one simply reason: to create a buffer zone between the more populous southern states and raiding Kiowa and Comanche Indians, who stole property, took captives, and killed without mercy. Native peoples form the foundation stone of Texas history. Many of those tribes died out, assimilated into other, more powerful tribes, or were pushed off traditional hunting grounds and homesites. The most dangerous and feared tribe did not originate in the area that became Texas, but it nevertheless became the most identified with Texas: the Comanche. Gwynne’s history focuses on the most famous Comanche: Quanah Parker, the son of Cynthia Ann Parker who as a child was captured during a raid and raised as one of their own.

The Blood of Heroes: The 13-Day Struggle for the Alamo—and the Sacrifice that Forged a Nation, James Donovan (Little, Brown and Company, 2012)

The Alamo is a perennial topic in Texas, but no historian has dealt with the details of these thirteen days with the scholarship and insight of Donovan. With new sources from Mexico, Donovan paints a more accurate portrayal of what took place in San Antonio in the early spring of 1836, not only within the Mexican lines (which is unique in itself) but also what was taking place within the adobe walls of the mission-fort. The Alamo and its history have long been obscured with the overgrowth of legend and myth, which for many Texans have become sacred truths. However, we do not honor the sacrifice made by the Texians and Tajanos at the Alamo by refusing to see the truth of what took place during those thirteen days. Donovan has done us the service of giving us the truth, stripped of its myth.

Big Wonderful Thing: A History of Texas, Stephen Harrigan (University of Texas Press, 2019)

Until Harrigan came along the definitive history of Texas was T.R. Fehrenbach’s 1968 Lone Star: A History of Texas and Texans. Harrigan’s book, which covers the vast sweep and scope of Texas history, not only now carries that mantle (his book is a genre buster)—and brings the history up to date—he does so with a style so inviting and approachable as to render Fehrenbach’s narrative as tired and worn-out. As we might say in Texas, compared to Harrigan, Fehrenbach looks like he’s been ridden hard and put up wet.

William Sydney Porter (O. Henry), no relation to Kathrine Anne, did live in Texas for a time, but was not from Texas; he was born in Greensboro, North Carolina.

After my praise of Porter you may wonder why she and her two short stories and novella are not on this list. I have no excuse other than to say she never turned her pen to paint a word portrait of Texas and Texans in book form. This list represents essential books about the Lone Star state and Lone Star folks.