The Siege and Fall of the Alamo (1914), Part 1

The First Feature-Length Alamo Film

The play seems to please the patrons and is pronounced by historians as a great reproduction.

The San Antonio Light

Humans create because they are compelled or called to do so. They long to leave a legacy, a mark to show future generations they valued that which was true, good, and beautiful. So when works of creativity that predate our own generation are lost, the loss is not just a loss of artistry and history, it’s a loss of collective memory—of knowing and appreciating those who went before.

As a Texan, I feel the loss of Henry Arthur McArdle’s Lee at the Wilderness (1872) and Dawn at the Alamo (1875), paintings consumed in the 1881 Texas Capitol fire. I’ve seen grainy photographs, but I would love to have seen these canvases in their bold colors. The same goes for the 1911 black and white movie The Immortal Alamo—a film lost to time, only stills survive.

When it comes to old films a leading cause was the instability and flammability of nitrate, which all films up to the 1950s were printed on. Many either decomposed into an unprojectable goo or combusted into ash. Then there was the destruction by studios to reclaim silver from film stock or to clear their shelves after a film’s theatrical release. And if the studio was a small independent production company there generally were no funds to preserve prints nor inclination to do so.

Like The Immortal Alamo, two such lost films made toward the beginning of the motion picture industry concern that 1836 battle: The Fall of the Alamo (1914) and The Siege and Fall of the Alamo (1914).

The Fall of the Alamo

All that is known of The Fall of the Alamo is that it was produced by the State of Texas and starred Ray Myers. No other information is known about its production.

The Siege and Fall of the Alamo

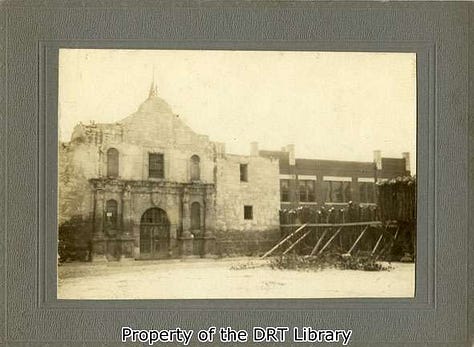

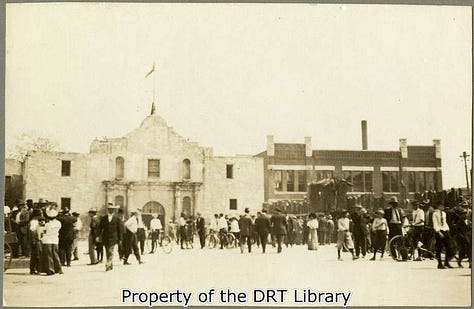

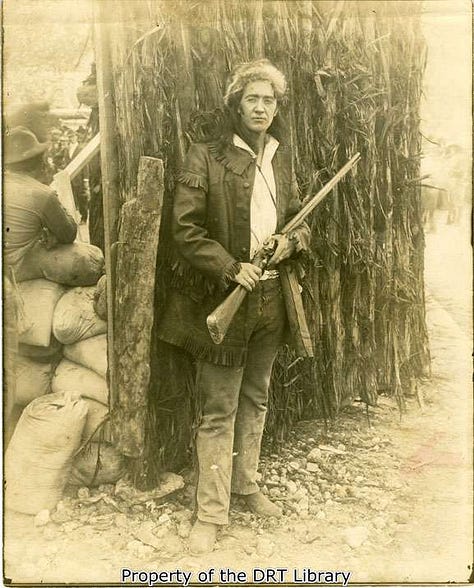

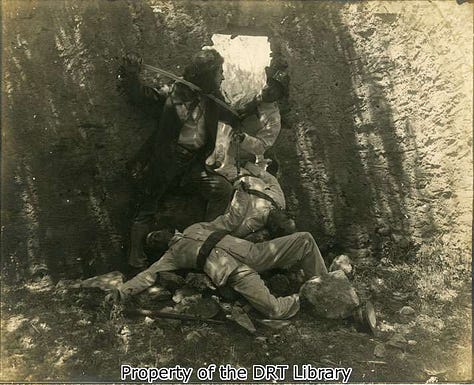

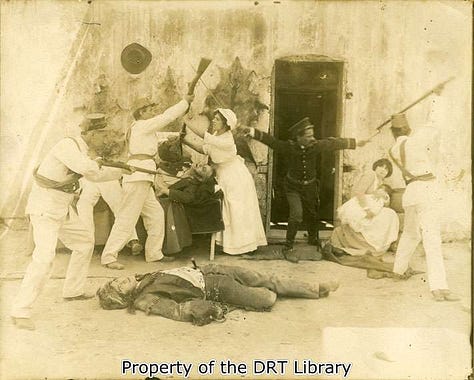

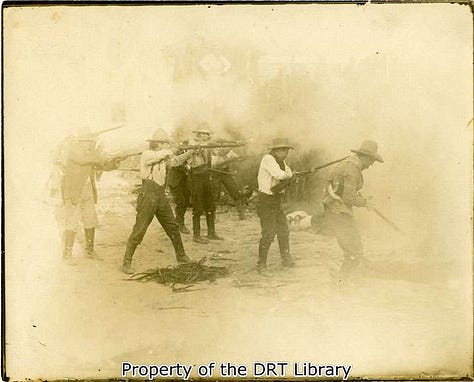

More is known about The Siege and Fall of the Alamo, though all prints are lost. All that survive, at least according to the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, are six stills. However, four of the photographs are disputed by film historian Frank Thompson, who claims they are stills from the first known Alamo film, The Immortal Alamo: the unidentified actor portraying David Crockett, Crockett struggling against a Mexican soldier, a woman defending the bedridden James Bowie, and a group of Texians firing their rifles.

Thompson doesn’t challenge the two photographs of the Alamo chapel with a reconstructed wooden palisade. If these images are from the set of The Siege and Fall of the Alamo—the only known production to actually film on location at the Alamo—then the photograph of the lone Crockett standing in front of a wooden structure, whom some have identified as Ray Myers, the only known actor in the production, would seem to be a still from the 1914 film and not the earlier one.

Not everyone was convinced The Siege and Fall of the Alamo was even made. Former historian for the Texas Film Commission, James Buchanan wrote in 1972,

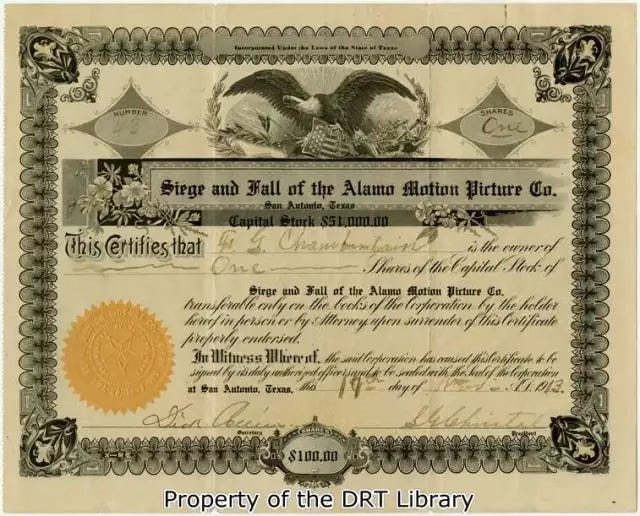

One of the first expressions of Texan interest in moviemaking was made in 1913, when four men from North Texas traveled to San Antonio with serious plans to form a corporation for production of a series of silent films based on the siege and fall of the Alamo. A charter was granted and stock was sold at one hundred dollars a share. Many prominent Texans bough shares; but the project flopped, and three years later the charter was forfeited because of failure to pay franchise taxes on $50,000 in capital stock.

Though the series of films may have been abandoned, The Siege and Fall of the Alamo was produced.

Evidence for the production of the film appears in the Library of Congress, where a copyright was registered:

The Siege and Fall of the Alamo

This motion picture shows the collection of Texas forces

innear the Alamo. The approach of the Mexican forces and the demand by Santa Anna to surrender the guns owned and held by the citizens of Gonzales. The refusal of the Texans. Preliminary fight in which the Texans are victorious. The surrender and abandonment of the Alamo by the Mexicans. The occupation of the Alamo by the Texans. Approach of Santa Anna and his army and demand by him for the unconditional surrender of the Alamo. Refusal by the Texans. Fight for possession of the fort. Fightandafter and protracted struggle; the fort finally captured by the Mexicans in consequence of the killing of all the Texans.

Further evidence appeared on page 6 of the June 2, 1914, edition of The San Antonio Light. Under a column titled “Amusements” this review appeared for The Siege and Fall of the Alamo, which premiered the day before:

The greatest day’s business in the history of the Royal Theater is what the management reports for yesterday, it being the first day of the “Siege and Fall of the Alamo,” the made-in-San-Antonio picture play of that great historical event. The morning and afternoon shows drew splendid houses, but at night they were forced to stop the sale of tickets on two different occasions. The picture is a splendid piece of photography, clear in every detail, and the acting is perfect. The leading character, Travis, Bowie and Crockett, being excellently portrayed, and the make-up of the artists playing the parts perfect. The play seems to please the patrons and is pronounced by historians as a great reproduction.

In the same edition, on page 11, the management of the Royal Theater, “The Largest and Most Sanitary Theater in San Antonio,” which was “Devoted Exclusively to Motion Pictures,” placed two advertisements for The Siege and Fall of the Alamo. According to the managers the film was “The Season’s Greatest Success” and that it was “Made in San Antonio at a Cost of More Than $35,000.00.” The ad also claimed the film was “A Correct Reproduction of the Most Tragic Event in Texas History” captured on “5 Great Reels,” which included “Perfect acting—superb photography—cast of 2000, and would be shown again that day and the following day. So, the managers advertised, audiences should “Be sure and see it—send the children.” And you couldn’t beat the admission: 10 cents for children and 20 cents for adults.

At five reels, The Siege and Fall of the Alamo had the distinction of being the first feature-length Alamo film.

I only wish I could watch it.

“‘A Splendid Piece of Photography’: The Siege and Fall of the Alamo (1914),” Inside the Gates, December 2, 2011.

James R. Buchanan, “A Look at the Texas Film Industry,” Texas Business Review, vol. 46, no. 1 (January 1972), 8.

The San Antonio Light (San Antonio, Texas), vol. 34, no. 133, ed. 1 (Tuesday, June 2, 1914), The Portal to Texas History, The University of North Texas.

Siege and Fall of the Alamo Motion Picture Company, “The Siege and Fall of the Alamo” (1914), Library of Congress Motion Picture Copyright Description Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, reg. no. MU 161, class M, 1912–1977.

Frank Thompson, Alamo Movies (East Berlin, PA: Old Mill Books, 1991), 21, 22.

Frank Thompson, The Star Films Ranch: Texas’ First Picture Show (Plano: Wordware Publishing, 1996), 54.

Y’allogy is an 1836 percent purebred, open-range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is created by a living, breathing Texan—for Texans and lovers of Texas—and is free of charge. I’d be grateful, however, if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber and/or purchasing my novel.

Be brave, live free, y’all.

I truly believe that no information gets lost ever. Of course, the material bearing that information can dissipate with time. But not the info itself. Not to speak about heroic acts. In some shape or form it still exists and will forever.

In our subsconcious there are much more of that than we could imagine. I do know that.