The Immortal Alamo (1911)

The First Alamo Film

Y’allogy is 1836 percent pure bred, open range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is free of charge, but I’d be much obliged if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber. (Annual subscribers of $50 receive, upon request, a special gift: an autographed copy of my literary western, Blood Touching Blood.)

They butchered history.

–Paul H. McGregor

During a New York winter in 1909 Gaston Méliès decided he needed to seek a warmer climate. The change wasn’t for his health, though he didn’t mind escaping temperatures that were colder than his native France. The change was to provide greater opportunities for his movie studio. Filming outdoor scenes during the winter in New York was out of the question. And besides, the change of scenery would give his audience something fresh to look at—something exotic and romantic.

Méliès didn’t own the company outright, he was in partnership with his brother Georges, who had become famous for his 1902 groundbreaking science-fiction film A Trip to the Moon. Gaston was in New York to protect their rights against American producers. But now it was time to abandon the Empire State. Other filmmakers were, and for the same reasons. Nestor Film Company, which later became University Pictures, and D. W. Griffith of The Birth of a Nation fame (and who would go on to produce an Alamo movie: The Martyrs of the Alamo), moved to California to escape litigious patent-holder Thomas Edison, the harsh New York winters, and high production costs.

Méliès, however, was unsure of where he wanted to relocate the company. He sent his son Paul and director Wallace “Old Man” McCutcheon on a scouting mission to find a new location. Two weeks later, they cabled that they had found the perfect location. “A place that had never appeared before moving picture cameras and yet was so abundant in beauty and dramatic and scenic possibilities,” film historian Frank Thompson wrote, “that the company would never want to return to New York City.” They found San Antonio, Texas.

By early January 1910, Méliès had leased a two-story house located on a twenty-acre tract, which became known as Padre Park, near Mission San José, across the San Antonio River from the (now abandoned) Hot Wells Hotel and Spa. He dubbed the place, “Star Film Ranch.” It was from here, in 1911, seventy-five years after the events that transpired at Mission San Antonio de Valero, that Méliès put on celluloid the first known reenactment of the siege and battle of the Alamo.

San Antonio was chosen for its sunshine and military history. After moving in, McCutcheon told a local reporter: “There is at Fort Sam Houston a splendid opportunity for a series of brilliant pictures that must necessarily appeal to the American who has a martial spirit and is interested in this country’s arms.” Initially, Star Films wanted to produce an ambitious history of San Antonio, one which was “historically current” but with “ample romance in it,” McCutcheon said. He believed the San Antonio picture would be “one of the greatest films of the year” and would “appeal to the masses.”

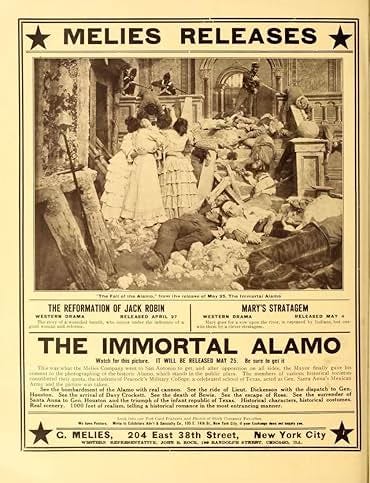

That film was never produced. In it’s place was The Immortal Alamo, directed by William F. Haddock and written by Wilbert Melville.

Melville had the daunting task of boiling down the thirteen day siege and battle, and the defeat of Mexican president and general Antonio López de San Anna at San Jacinto—and include a romantic element—into a script that could be shot on one, ten minute reel.

The story is loosely based to the Greek tragedy of Helen and the siege of Troy told in Homer’s The Iliad. But instead of going off with her Paris, the “Helen” of The Immortal Alamo, Lucy Dickenson (carelessly based on the real-life Susanna Dickinson and played by Edith Storey), rebuffs the advances of a Mexican man, Navarre, portrayed by Frances Ford (director John Ford’s older brother) in brown face. When her husband, Lieutenant Dickenson (William A. Carroll), is sent from the Alamo by Colonel Travis (William Clifford) to seek reinforcement from Sam Houston, Navarre makes unwanted advances toward Lucy. When Travis learns of this, he throws Navarre out of the mission-fort. Navarre informs Santa Anna that the defenders inside the Alamo are few in number and can easily be defeated. Santa Anna thanks Navarre for the information and lets him decide on an appropriate reward. Navarre asks for the first pick of the surviving women.

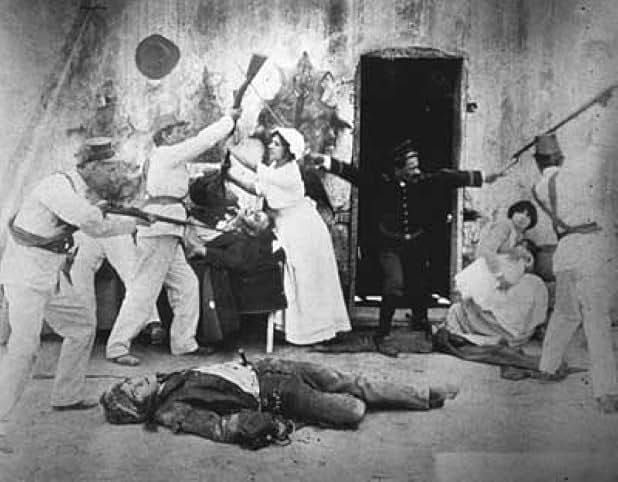

With his battle plan set, Santa Anna attacks. When Mexican troops breach the walls, which have been destroyed by cannon fire, they find nearly all the defenders dead, including Crockett (portrayed by Otto Meyer, though there is some doubt about this). Travis and four others have survived, but are quickly put to the sword. Lucy and two other women and three children are then allowed to leave the fallen fort.

Like a panther to the prey, Navarre pounces on Lucy and within a whisker’s width of forcing her to marry him—never mind that she’s already married—Lieutenant Dickenson, General Houston, and group of Texians descend on the Mexicans and triumphant over them, with Dickenson killing Navarre and reuniting with his wife, giving the fall of the Alamo a happy, love-filled ending.

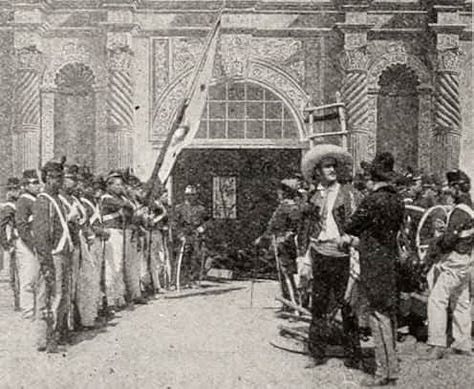

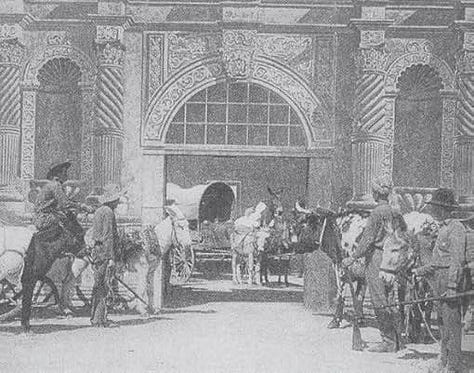

The production of The Immortal Alamo was an ambitious undertaking. Besides the stock company, there were more than one hundred cast members and extras. In the words of one contemporary reporter, “every available actor, cowboy, and ranch hand” auditioned. The cadets from the nearby Peacock Military College made an appearance. Méliès and Haddock believed the cadets’ shakoes, blue coats, and white pants were close enough to the uniforms worn by Mexican troops in 1836. Even Méliès had a role: the padre who conducts the forced marriage between Navarre and Lucy.

The exact location of principal photography is a mystery. According to the trade paper The Nickelodeon, filming would be “taken at the actual spot where [the battle] took place.” It didn’t. The “actual spot” was San Antonio in general. Méliès did ask to film in the Alamo chapel but was turned away by the Daughters of the Republic of Texas. San Antonio’s mayor, Bryan Callaghan Jr., however, did allow the company to shoot on city owned property: the square in front of the shrine. But since the film as been lost, it’s impossible to determine how much was filmed outside the actual Alamo.

Based on surviving photographic stills, some of the interiors were undoubtedly filmed at Star Film Ranch, given the painted quality of the sets. Other interiors, however, show actual stone walls as a backdrop. These could have been filmed in one of the other San Antonio missions. Mission San José is most likely since it had a roofless chapel at the time, as did the Alamo in 1836, and it was located near Star Film Ranch.

The Immortal Alamo was an extravagant production, “the biggest, most expensive, most important film [Star Films] produced in Texas, or anywhere else,” according to Thompson. It was also, if you believe the newspapers and trade journals at the time, a historically accurate film. The Meriden Daily Journal praised it as “A great historical military production.” The Film Index wrote,

The historical societies of Texas contributed their share to make the picture correct in every detail and this really should prove to be one of the sensations of the present year. The romance has been blended so closely with the story of the siege and fall of the Alamo that its benefit as a historical subject has been enhanced by the attractiveness with which the story is presented.

Later, The Film Index claimed, “The story recounts one of the saddest but most heroic events in the fight for Texas’ independence, in the making of which the Méliès company took unusual care to have every detail exactly as history tells and their efforts will undoubtedly be well repaid” The Moving Picture World said, “here is given a historical drama which will rank immediately with the important educational films.” Monograph wrote, “It would be a stolid audience indeed that failed to respond to the thrilling scene inside the Alamo.” And The Nickelodeon told audiences,

All the data relating to this siege has been obtained from direct descendants of the illustrious warriors who sacrificed their lives in fighting for their country during this siege. These native Texas [sic], who are thoroughly imbued with the intense patriotism with which their forefathers were inspired, have entered into this remarkable work of the Méliès company and are extending every help and giving their most eager interest and assistance in reconstructing this great historical event. Everywhere the company has been supplied with information and documents which will make this series of historical events unique in the annals of moving picture photography. The company has covered the ground most thoroughly by the Mexican border, and has lived over again the experiences of those who fought for the freedom of the Lone Star state.

And yet, like most Alamo films, the producers of The Immortal Alamo took extravagant liberties in “reconstructing this great historical event.” Paul H. McGregor, a moviegoer from Temple took umbrage with the production’s historical liberties. In a letter published in the New York Dramatic Mirror in July 1911 Mr. McGregor complained: “They butchered history.” He said, “Lieutenant Dickinson was not at the Battle of San Jacinto, but perished in the Alamo. Would not this true history have made a stronger play than to butcher sacred history in order to have the hero stab the villain and catch the heroine in his arms? Mockery!”

The editors of the New York Dramatic Mirror disagreed with Mr. McGregor’s historical assessment. They praised the filmmakers, claiming their “excellent judgment has been used in subordinating the [romantic] story just enough to leave the historical subject prominent.” Never mind the fact that the romantic story is ahistorical.

✭ ✭ ✭

Though Méliès and his team found San Antonio a land “that had never appeared before moving picture cameras and yet was so abundant in beauty and dramatic and scenic possibilities, that the company would never return to New York,” Méliès decided not to stay in San Antonio. By the time The Immortal Alamo was released, on May 25, 1911, Méliès had shut down Star Film Ranch and abandoned Texas, moving the company to Santa Barbara, California. I guess the Texas summer was just as brutal as the New York winters.

Star Films continued to make movies for at least three years after leaving Texas. Méliès moved to Corsica, where he died in 1915. His son Paul sold what was left of the company two years later. Most of the seventy films produced by Star Film Ranch, including The Immortal Alamo, are now lost. (One film, a Western called Billy and His Pal, was discovered in New Zealand in 2010 and restored.)

When The Immortal Alamo arrived in theaters the New York Dramatic Mirror wrote, “It has long been a dream of American film makers to picture the fall of the Alamo.” Gaston Méliès and Star Films Company was the first to do so, but they weren’t the last. Since then at least sixteen films, long and short, have been produced.

I’m grateful for each one because in their own way each one helps us remember the Alamo.

✭ ✭ ✭

Frank Thompson, Alamo Movies (East Berlin, PA: Old Mill Books, 1991).

Frank Thompson, The Star Films Ranch: Texas’ First Picture Show (Plano: Wordware Publishing, 1996).

✭ ✭ ✭

Support Y’allogy—

Much obliged, y’all. Be brave. Live free.

what an epic story!

Thank you for this story. I wrote about the fall of the Alamo today, like many others it seems, but yours is a story I had never heard–and I was a film major in college! In Austin! I wish we could still see that film.