The MURDER Steer

Big spreads sometimes hired men to be hard.

J. Frank Dobie

When the country was at war with itself, and too few men in Texas to tend them, longhorns roamed the rough lands of South Texas wild and free. Though no one knows the exact numbers, they could be counted in the millions. From 1866 to 1890 some ten million head were trailed out of Texas to northern railheads. At war’s end, men and families streamed into Texas, escaping the shambles that had become the southern economy. Some of those men, if they could find a market for them, saw bags of money bound up in the brindle hides of those free range cattle. Lord knows, as a cash industry, cattle in Texas were virtually worthless, fetching no more than four dollars a head—if you could find someone with four dollars to spend. But markets north of the Lone Star state, where the appetite for beef was fattening, cattle could bring upwards to forty dollars a head. And so was birthed the great cattle drives and the boon of the cowboy myth.

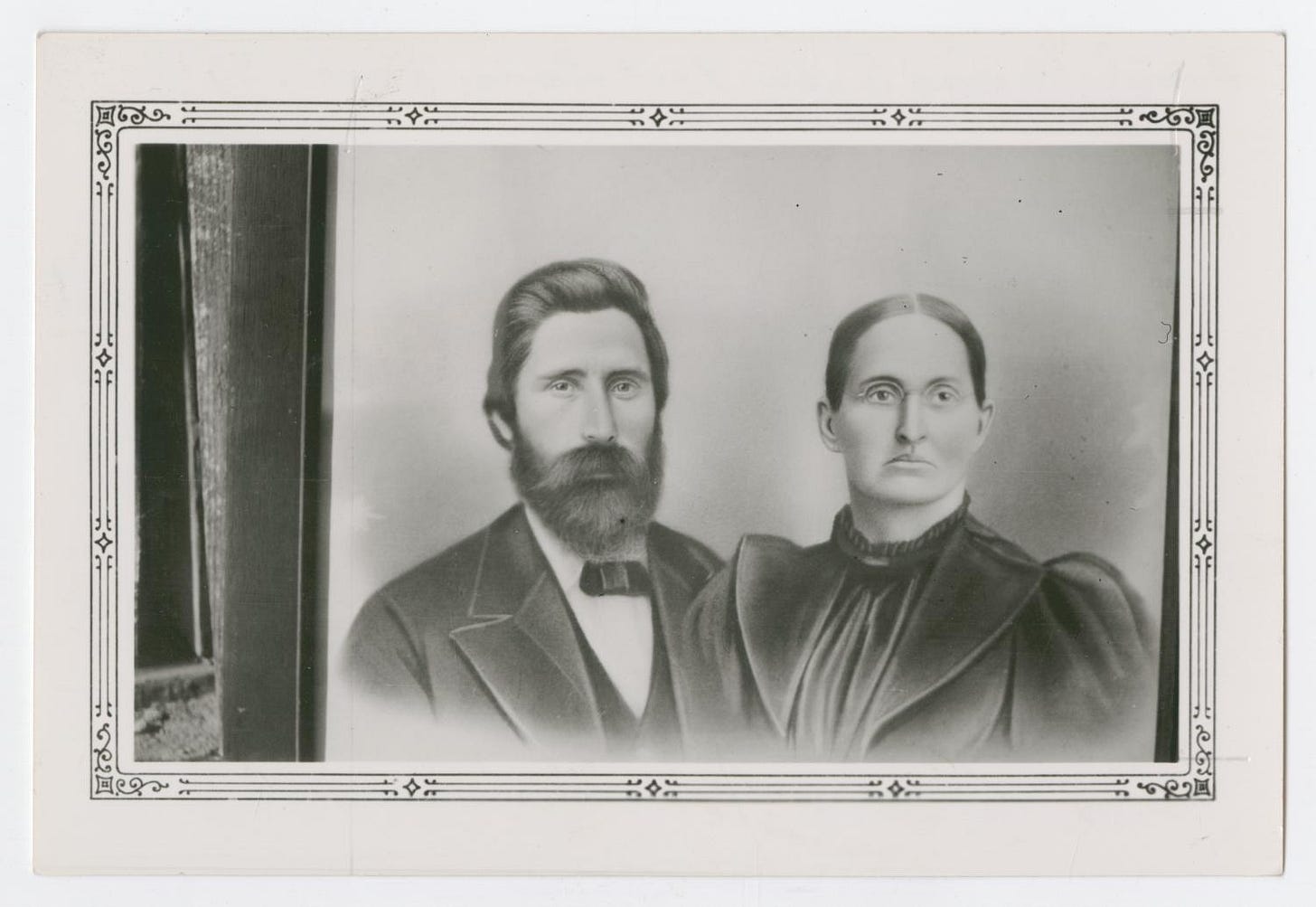

One of the men who fled to Texas after the war was Henry Harrison Powe, a Mississippian who dropped out of college to fight for the Lost Cause, losing not only the cause but everything he owned, including an arm. Powe settled in the broken brush country of the Trans-Pecos, a harsh and unforgiving land between the Pecos River and the Rio Grande. He ran a small cattle operation—the HHP. Men who lose as Powe lost find themselves either broken or hardened. For Powe, one-armed as he was, the loss toughened him. He was as gritty and resilient as the longhorns that roamed the range. A man had to have sand to live through what he endured, to live and work in the Devil’s playground—and to bury the bullet-riddle body of a murdered nephew, who had been shot eleven times, in the hard caliche that makes up that part of Texas. As rough a cob as he was, Powe was an honest, hardworking man, without a contentious nature.

Which makes what happened on January 28, 1890, all the more tragic.

Howdy, y’all. Welcome to Y’allogy. Pull up a chair and put your boots up.

Before going on to enjoy a few more minutes of pure Texas goodness, I’d be obliged if you’d consider becoming a subscriber—either paid or free. If you sign up as a free subscriber I’ll send you a baker’s dozen of my favorite Texas quotations. If you sign up as a paid subscriber, or upgrade to paid, I’ll send you the same baker’s dozen of Texas quotations, as well as a chili recipe from the original Chili Queens of San Antonio. Either way, I appreciate your consideration.

Powe, along with other small outfits, held a joint roundup in the area of the Leoncita waterholes in northern Brewster County—which, at 6,192 square miles, is large enough to fit the states of Rhode Island and Delaware in it twice over, and still have room to stretch your legs. These ranchers intended to brand calves that had been missed during the fall roundup. When the herd was gathered, it numbered somewhere between two thousand and three thousand head.

By vote, the ranchers agreed on a respected man to serve as roundup boss. He would settle disputes and had the final say over the ownership of unbranded cattle.

As the roundup got underway, the largest operator in that part of the country, Wentworth and DuBois, who took no part in the proceeding, sent a man to make sure none of their cattle were slapped with another outfit’s brand. The man they sent was Fine Gilliland. Some accounts say Mannie Clements, a cousin to John Wesley Hardin and a relation by marriage to Killin’ Jim Miller, was also present.

As cowboys cut out and roped unbranded animals, the roundup boss and another range man spotted an orphaned brindle yearling bull. It didn’t following any particular female, but they had seen it with an HHP cow that shared similar markings. They told Powe the yearling bull was his animal. Unsure, Powe asked the men if they were certain. They were, and swore the brindle belonging to a HHP cow. That was good enough for Powe. He rode into the herd, cut the brindle out, and trailed him to a small cut of cows and calves being held by his son, Robert. He then returned to the main herd.

Other outfits didn’t dispute Powe’s claim to the yearling bull, but Gilliland did. Under orders by Wentworth and DuBois to challenge possession of any maverick—unbranded, free range cattle of unknown ownership—Gilliland rode to where the boy held the HHP cut and asked, “Does that brindle bull have a mother here?”

“No sir. But the boss told Father it belongs to an HHP cow.”

“He’ll pay hell taking it unless he produces the cow.” Gilliland eased his horse in among the HHP cattle, separated the brindle bull, and trotted him back to the main herd.

Working the edge of the main herd, Powe saw the bull he had just penned in his cut looping back. Gilliland trailed behind. Powe trotted out and spoke to Gilliland, while the yearling bull joined the larger herd. After exchanging words, Powe rode back into the heard and cut the brindle out one more time. Gilliland moved his horse in to stop him. More words passed between the two men before Powe lopped to the far side of herd, where he borrowed a Colt revolver from a friend’s saddlebag.

Riding back into the midst of the main herd, Powe found the brindle bull and started him toward the HHP cut. About half way to HHP cattle, Gilliland saddled up to Powe, rope in hand, and tried to put a loop over the horns of the yearling. He missed. Powe had had enough. He decided he’d rather kill the bull than let Wentworth and DuBois put their brand on him. He pulled the pistol and fired. He too missed.

It’s hard to say whether Gilliland, whom some claimed to be a notorious gunman, believed Powe was shooting at him or whether in the argument over the bull he lost his cool and decided to gun down Powe, but within a matter of seconds Gilliland had dismounted and shot Powe from his horse. The one-armed Mississippian was dead before he slipped from the saddle.

According to J. Frank Dobie in The Longhorns, “In all probability [Gilliland] was honest in claiming the brindle maverick for his employers. Perhaps he hoped to make a reputation. There was a strong tendency on the range for little owners to ‘feed off’ any big outfit in their country. The big spreads sometimes hired men to be hard.”

Regardless, Gilliland remounted and dug his spurs into the flesh of his horse. Powe’s son did the same, racing to Alpine to notify the Texas Rangers of his father’s murder. The cowboys who remained at the roundup branded-out and castrated the remaining calves and yearlings, including the HHP stock. The brindle bull was dragged to the branding fire last. There was a short discussion about whether they should slap the HHP brand on it or cut it loose. What they decided became part of Texas lore.

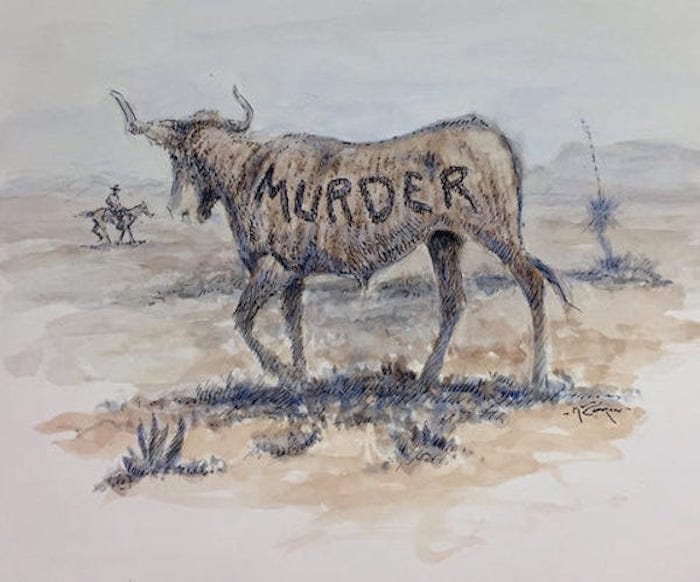

One man retrieved a running iron—a branding iron with the end curved up or bent, used to “freehand” a brand on an animal. The brindle was thrown on its right side, exposing the shaggy winter hair on the left, where cowboy with the running iron burned MURDER across the bull’s ribs, from its shoulder to its flank.

“Turn him over,” the man said. The cowboys did. With the running iron newly hot, the man branded the bull’s right side: JAN 28 90. Without castrating or earmarking him, the cowboys released the now branded brindle bull yearling to roam those wild lands.

A few days after the murder of Henry Powe, Brewster County Deputy Sheriff Thalis Cook and Texas Ranger Jim Putnam tracked down Fine Gilliland in a canyon nestled in the desert mountains of West Texas. Cook asked for his identity. Gilliland didn’t answer but pulled his pistol and fired, hitting Deputy Cook in the knee and killing his horse. Ranger Putnam dismounted with his Winchester and shot Gilliland in the head. That place is now known as Gilliland Canyon.

What happened to the brindle bull with a brand no one wanted to claim is unknown. Robert W. Powe, the boy who witnessed the murder of his father on that January afternoon, later said the MURDER steer* was eventually rounded up and trailed to Montana.

Who knows.

Stories circulated in West Texas for years that the MURDER steer prowled the desolate Trans-Pecos as an outcast, never seen with other cattle—if seen at all. Like the mysterious Marfa lights that wink in the air of the desert night, the MURDER steer became a phantom. Those who claimed to have seen him always caught a glimpse of him at dusk, then he would vanish. Witnesses said his brindle coat turned ghostly grey, except where the running iron had burned MURDER into his side. The reddened hair that grew over the large scab had become corse and tangled. Some even said the bull’s eyes were blood red and glowed in the darkening light.

According to legend, the MURDER steer wandered the wastelands of West Texas searching for the man who burned the horrid brand into his side, and that whenever he appeared foul play was in the offing. It was said that anyone who crossed the bull’s path was bound for the grave, and that one night the head of the MURDER steer burst through the bunkhouse window of the Wentworth and DuBois outfit and stared straight into the soul of a cowboy. The next day he suffered a tragic accident, died, and was buried in the same hard caliche that bore the bones of Henry Powe.

Though the legend of the MURDER steer is little known today, it did survive and spread into the popular culture well into the twentieth century. On May 13, 1960, the television series Rawhide aired “Incident of the Murder Steer.”

And in 1983, Canadian country and western singer Ian Tyson recorded “Murder Steer” on his Old Corrals and Sagebrush & Other Cowboy Culture Classics.

* I’m using the phrase MURDER steer here and elsewhere out of cultural convention since this is how the yearling bull was described in folklore and popular culture. Technically, the animal was never a steer since it was never castrated—or at least its castration was never mention in any of the tales I read about the animal.

J. Frank Dobie, The Longhorns (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990), 61–64.

What a fascinating story. The number of unheard cowboy stories must be too high to count

What a great Texas tale! Thanks for sharing this!