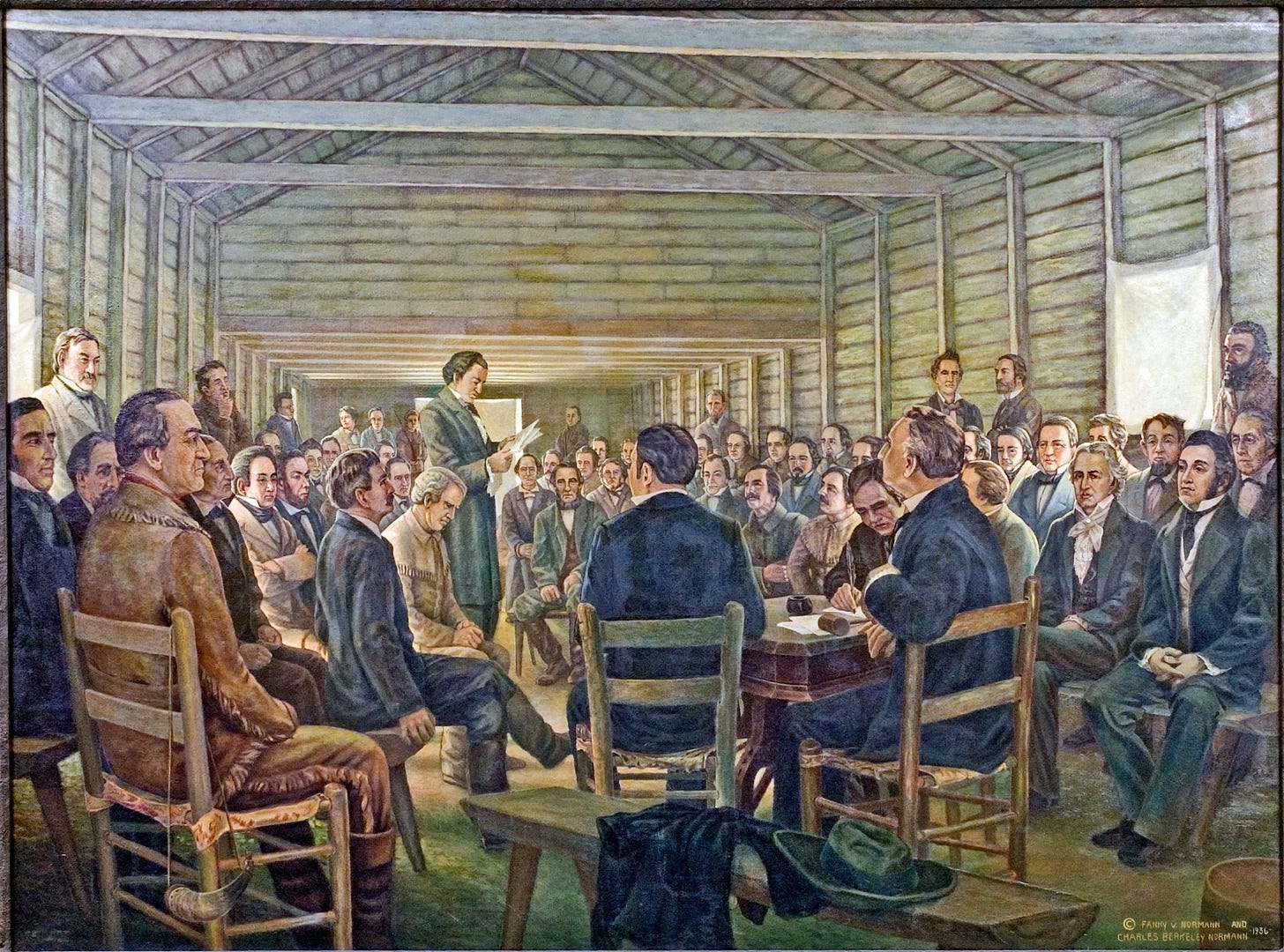

The Convention of March, 1836

There are fifty-eight signers of the Declaration of Independence which this convention promulgated on March 2nd.

Clarence R. Wharton

Texas has produced a number of fine professional historians who write erudite articles and books about their specialized subjects of study. Texas has also produced a number of fine amateur historians who write throughly researched books about Texas. Among both, Texas has also produced charlatans who use history like the butt of a Kentucky long rifle to topple heroes and strike a blow for political ends. Stephen Hardin (Texian Iliad) and H. W. Brands (Lone Star Nation) fit in the first category. Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and Jason Stanford (amateurs all) fit in the last category—especially their historical quackery Forget the Alamo. Stephen Harrigan (Big Wonderful Thing) and Clarence Wharton (The Republic of Texas) fit in the second category.

While Harrigan is an amateur historian, he is a professional writer. Wharton, on the other hand, while an amateur like Harrigan, wasn’t a writer by trade. He was an attorney. Born Clarence Ray Wharton in Tarrant County on October 5, 1873, he was admitted to the bar by his twentieth birthday. In 1901 he moved to Houston and became a lawyer at Baker, Botts, Baker, and Lovett. Within five years he became a full partner, representing Houston Lighting and Power Company, Houston Gas and Fuel Company, and Houston Electric Company. A member of the Harris County Historical Society, serving as vice president in 1923, Wharton was active in writing Texas history. Before his death on May 1, 1941, he contributed to and edited the five-volume Texas Under Many Flags (1930), as well as penned eight separate books of history and biography:

The Republic of Texas: A Brief History of Texas from the First American Colonies in 1821 to Annexation in 1846 (1922)

El Presidente: A Sketch of the Life of General Santa Anna (1924)

San Jacinto: The Sixteenth Decisive Battle (1930)

History of Texas (1935)

Satanata: The Great Chief of the Kiowas and His People (1935)

History of Fort Bend County (1939)

L’Archeveque (1941)

Gail Borden: Pioneer (1941)

Though an amateur historian, Wharton took great care with his research. In the opening pages of The Republic of Texas he wrote, “I have consulted every work bearing upon Texas History which as ever been published as far as I know, and many original sources of information as well.” In that volume, dedicated to the years between Austin’s colonization efforts to the annexation of Texas by the United States, Wharton addressed four distinct periods: Anglo-American settlement, the revolution, the Republic, and annexation. As part of the section dealing with the revolution, he addressed the Convention of 1836, which met at Washington-on-the-Brazos and produced a Declaration of Independence from Mexico. This is what Wharton said about that convention.

For the fourth time in our history, a convention of all Texas met on March 1, 1836, at Washington on the Brazos. Without a moment’s delay, a permanent organization was had with Richard Ellis, from Red River, as chairman. The General Council was still in session at San Felipe, but its conspicuous failures earned it the contempt of the new convention.

[. . .]

As soon as the convention was ready for business, George C. Childress, of the Red River country, moved the appointment of a committee of five to draft a declaration of independence. Tradition tells that he had already prepared the draft of the declaration and that it had been approved by Houston and others to whom it had been submitted. The committee brought in the draft the next morning, and when it was read on motion of General Houston, it was unanimously adopted early in the morning of March 2, 1836, which by the way was his 43rd birthday.

On the 4th Houston was again chosen commander-in-chief, and on Sunday morning, March 6th, the same hour the Alamo fell, he left Washington with an escort of four men riding towards San San Antonio. At that time it was known to Houston and to the convention that there was no hope for Travis, and that no help could be expected from Fannin and Grant and those mad, mislead men who had lately moved towards remote Matamoros while Santa Anna’s army marched directly into the heart of Texas.

In a cold March rain, the five horsemen rode west while sad, sober faces bade them goodbye and turned to the business of the convention.

Speaking of this occasion, General Houston said many years later: “The only hope lay in the few men assembled at Gonzales. The Alamo was known to be under siege, Fannin was known to be embarrassed, Ward, Morris and Johnson destroyed. All seemed to bespeak a calamity of the most direful character.” It was under these auspices that the General started with an escort of two aides, a captain and a boy, yet he was sent to produce a nation and defend a people.

Travis’ last message, sent from the Alamo on March 3rd, reached Washington on Sunday morning, just before Houston left, and about the hour the Alamo fell, and was read in the convention at its opening session on that day, but there was nothing the convention could do except to adopt a resolution that “1,000 copies of the letter be printed,” and this they arranged for.

With independence declared and Houston on the way west, the convention addressed itself to the formation of our first constitution, for our fathers were firm believers in constitutional government. With them it was as natural for a new government to have a solemnly written constitution as for an infant to be christened and bearing his father’s name.

In these awful environments, the constitution of March 1836, was written, debated and adopted, and prepared for submission to the people for ratification. But no man knew when if ever there could be a submission at a general election, and until this was done a government ad interim was provided. David G. Burnet was chosen president and the Mexican-Spaniard Lorenzo de Zavala, lately fled from Mexico to escape Santa Anna, was chosen vice-president.

The last hours of the convention, which finished its labors late on the night of March 17th, were hastened by a rumor that a Mexican army was near at hand. News of the fall of the Alamo had come by a courier on the 15th, but there was no unseemly haste on the part of the convention.

[. . .]

There are fifty-eight signers of the Declaration of Independence which this convention promulgated on March 2nd. Forty of them were under forty years of age. Many of them were men highly educated and of rare experience. Nearly all of them came from the southern states, eleven from the Carolinas. There were two native Texans, Jose Antonio Navarro and Francisco Ruiz, both from Bexar. There was an Englishman, a Canadian, a Spaniard born in Madrid, an Irishman and a Scotchman.

Source:

Clarence R. Wharton, The Republic of Texas, reprint (1922; Corpus Christi: Copano Bay Press, 2021), 115–118.

The piece you just read was 1836% pure Texas. If you enjoyed it I hope you’ll share it with your Texas-loving friends to let them know about Y’allogy.

As a one-horse operation, I depend on faithful and generous readers like you to support my endeavor to keep the people, places, and past of Texas alive. Consider becoming a subscriber today. As a thank you, I’ll send you a free gift.

Find more Texas related topics on my Twitter page and a bit more about me on my website.

Dios y Tejas.