Eyewitness at the Birth of Texas

William Fairfax Gray records the day when Texas became Texas

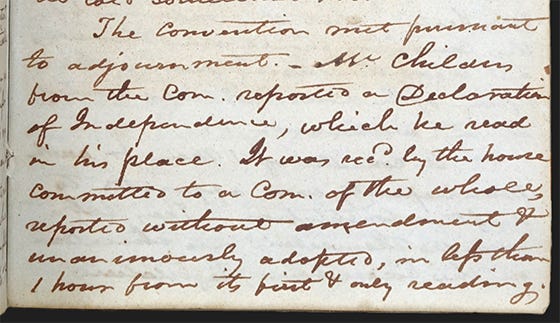

Mr. Childers . . . reported a Declaration of Independence.

William Fairfax Gray, Diary, March 2, 1836

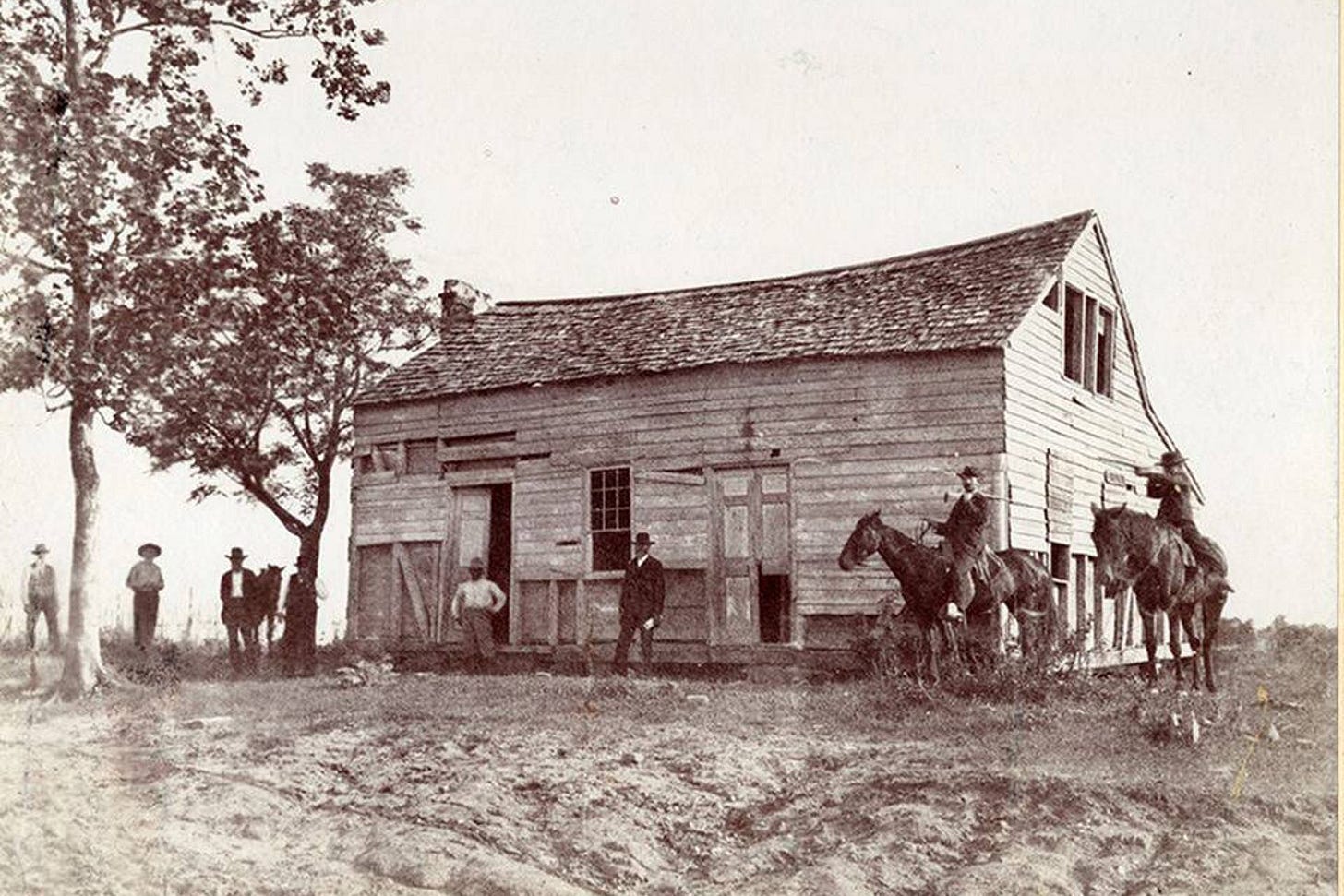

Chances are you’ve never heard of the man. Even Texophiles would have a difficult time recalling anything about the man at the mention of his name. And yet, he was an eyewitness to and chronicler at the birth of an independent Texas. Sitting in the drafty, unfinished home built by real estate developers Peter Mercer and Noah T. Byars, located in small town sporting a big name, William Fairfax Gray kept a diary of the proceedings of the Convention of 1836.

Born in Fairfax County, Virginia on November 3, 1787, William Gray would have lived his entire life in the Old Dominion if it wasn’t for the financial crisis of the early 1830s. Though he distinguished himself as a captain in the Sixteenth Regiment of the Virginia Militia in the War 1812, later to be promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1821, and was a practitioner of the law, the panic of 1833 and 1834 all but bankrupted Colonel Gray. Along with his wife Milly, the Colonel had twelve mouths to feed and was in desperate need to find “new fields of enterprise,” as one son put it, “and Texas just then loomed up as a land of promise.”1

He went to work as a land agent for two wealthy friends who managed to survived the financial panic—Thomas Green and Albert T. Burnely of Washington, D.C. Colonel Gray wound up in Texas in late January 1836 and became entangled in the political turmoil of the time. After hearing the call for a convention to meet at the newly formed town of Washington,2 Colonel Gray determined to take part. He was one of the first to arrive, securing lodging at the only boardinghouse in town. He found Washington “disgusting. It is laid out in the woods; about a dozen wretched cabins or shanties constitute the city; not one decent house in it, and only one well defined street, which consists of an opening cut out of the woods. The stumps still standing.” He concluded that Washington was “A rare place to hold a national convention in” and that the delegates “will have to leave it promptly to avoid starvation.”3

Howdy, folks. If you’re reading this from a post off social media, or a friend shared this with you, welcome. Pull up a chair, put your boots up, and stay awhile—and consider becoming a subscriber. If you’re already a subscriber, and like what you read, think about becoming a partner to keep Y’allogy going and growing by upgrading as a paid subscriber. But whatever y’all choose to do, I’m much obliged y’all are here.

Delegates who showed up in the unseasonable warm weather of late February arrived in their shirtsleeves. But in the wee hours of March 1 a norther raced down the plains, dropping the temperature to just above freezing—33 degrees—and hovered there throughout the convention’s doings. On that first day, delegates, forty-four in all, trudged through the cold to the Mercer-Byars house and shivered as the wind whistled through the boards and the clothcovered doorway and windows. Colonel Gray had hoped to be appointed secretary of the convention, but was not. Nonetheless, he was allowed to observe the proceedings. He kept a careful and faithful diary of what took place during the convention—more complete in some instances than the official journal—which was first published in 1909 under the title From Virginia to Texas.

On the morning of March 2, 1836, Colonel Gray and the delegates made their way back to the Mercer-Byars house. The convention was gaveled to order at 9:00 o’clock and before day’s end Texas was declared independent from Mexico. Here’s how the Colonel recorded it in his diary.

Wednesday, March 2, 1836

The morning clear and cold, but the cold somewhat moderated. The Convention met pursuant to adjournment. Mr. Childers, from the committee, reported a Declaration of Independence, which he read in his place. It was received by the house, committed to a committee of the whole, reported without amendment, and unanimously adopted, in less than one hour from its first and only reading. It underwent no discipline, and no attempt was made to amend it. The only speech made upon it was a somewhat declamatory address in committee of the whole by General Houston.

Assistant clerks were appointed, and, there being no printing press at Washington, various copies of the Declaration were ordered to be made and sent by express to various points and to the United States, for publication; 1,000 copies ordered to be printed at for circulation. A committee was appointed to procure and attend to the dispatching of expresses. Additional members attended, three from Nacogdoches, Rusk, Taylor and Roberts; Brigham from Columbia, Menard from Liberty.

A motion was made by Mr. Scoty that the members of the Convention should arm themselves and wear their arms during the session of the Convention. It was scouted at and withdrawn. A committee of one member from each municipality was appointed to draft a Constitution. They subdivided themselves into three committees, on the executive, legislative and judicial branches; Zavala chairman on the executive.

A copy of the Declaration having been made in a fair hand, an attempt was made to read it, preparatory to signing it, but it was found so full of errors that it was recommitted to the committee that reported it for correction and engrossment.

An express was this evening received from Col. Travis, stating that on the 25th a demonstration was made on the Alamo by a party of Mexicans of about 300, who, under cover of some old houses, approached to within eighty yards of the fort, while a cannonade was kept up from the city. They were beaten off its some loss, and amidst the engagement some Texans soldiers set fire to and destroyed the old houses. Only three Texans were wounded, none killed. Col. Fannin was on the march from Goliad with 350 men for the aid of Travis. This, with the other forces known to be on their way, will by this time make the number in the fort some six or seven hundred. It is believed the Alamo is safe.4

Of course, Fannin never made it to the Alamo. And as far as “the other forces known to be on their way,” only thirty-two brave men from Gonzalos—“The Immortal 32”—came to the Alamo’s defense. Little did Colonel Gray, or anyone at Washington know, that the Alamo would fall two days later, her 189 defenders killed and burned on funeral pyres.5

On Thursday, the 17th, Colonel Gray wrote in his diary, “The Alamo has now fallen, and the state of the country is becoming every day more and more gloomy. In fact, [the delegates] begin now to feel that they are hourly exposed to attack and capture, and, as on the approach of death, they begin to lay aside their selfish schemes, and to think of futurity. . . . The members are now dispersing in all directions, with haste and in confusion. A general panic seems to have seized them. Their families are exposed and defenseless, and thousands are moving off to the east. A constant stream of women and children, and some men, with wagons, cars and pack mules, are rushing across the Brazos night and day.”6

The Runaway Scrape had begun.

Colonel Gray escaped that same day, fleeing Washington across the Brazos River. Though he was not a delegate to the convention he grew to know those who were, as such he was able to secure a passport to leave Texas and return home to Virginia, where his family awaited him.

Department of State

Republic of Texas

28th March, 1836

William F. Gray having made application to this Department for leave of absence from the Republic of Texas, and having shown that his business is of such a nature as to justify his absence. Be it known to all persons, That the said William F. Gray has leave to be absent from the Republic of Texas for and during the term of * * * from date hereof.

By order of the President.

Sam P. Carson,

Sec’y of State7

Colonel Gray arrived at Fredericksburg, Virginia on the evening of Sunday, June 26.

Home.

He would return to Texas in 1837 and settle his family in Houston, where he practiced law and served the Republic of Texas as clerk of the House of Representatives, secretary of the Senate, and clerk of the Supreme Court. In March 1841, while visiting Galveston, he contracted a severe cold, which, on his return to Houston, developed into pneumonia. He never recovered. He died on April 16 of that year.

A.C. Gray, as quoted in At the Birth of Texas: The Diary of William Fairfax Gray, 1835–1838, reprint (Corpus Christi: Copano Bay Press, 2015), 6.

Renamed Washington-on-the-Brazos after independence to distinguish between it and the national capital of the United States.

William Fairfax Gray, Sunday, February 14, 1836, in At the Birth of Texas, 147.

Gray, Wednesday, March 2, 1836, in At the Birth of Texas, 167–8, emphasis in original.

The delegates and Colonel Gray learned of the Alamo’s fall on Tuesday, March 15.

Gray, Thursday, March 17, 1836, in At the Birth of Texas, 180–81, 82.

As quoted in At the Birth of Texas, 7.