Saddle Slickers, Heel Squatters, and Other Cowboy Names

The cow-boy.—the Cowboy! How often spoken of, how falsely imagined, how greatly despised (where not known), how little understood!

J. B. “Texas Jack” Omohundro Jr.

John Wayne’s classic movie The Cowboys celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 2022. Along with Red River, The Culpepper Cattle Company, and Lonesome Dove, The Cowboys remains one of the most vivid depictions of life on the trail put to film. Wayne plays aging rancher Wil Andersen, whose hands have deserted him for the gold fields. To get his cattle to market he’s reduced to hiring schoolboys, none older than fifteen—“between hay and grass,” Andersen says. Standing at the blackboard in the schoolhouse, Andersen looks over the young faces and says,

I don’t expect to get to Belle Fourche with one single head of beef, but I’m cornered, so I’m taking ya on. Now this is the way it’s gonna be: I’m a man and your boys. Not cowmen, not by a damn sight, nothing but cow-boys, just like the word says. And I’m gonna remind you of it every single minute of every day and night.

I recently rewatching that scene and it set me to thinking about the origin of the word cowboy. Growing up in Texas, which is synonymous with cowboy, I took it for granted that I knew all I needed to know about these cavaliers of the plains. I couldn’t have been more cattywampus.

A Brief History of the Word Cowboy

John Burnell Omohundro Jr., better known as “Texas Jack,” was the country’s first celebrity cowboy. A friend of William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, Omohundro appeared in the first stage productions featuring a cowboy, as well as performing in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows, demonstrating rope tricks. But he was no Bill-show cowboy. He was the real deal, having worked cattle in Texas and along the trails. In a pamphlet promoting Cody’s shows, Texas Jack wrote a description of the cowboy, including these lines: “The cow-boy.—the Cowboy! How often spoken of, how falsely imagined, how greatly despised (where not known), how little understood! . . . How sneeringly referred to, and how little appreciated, although his title has been gained by the possession of many of the noblest qualities that form the romantic hero of poet, novelist, and historian; the plainsman and the scout.”

How true. The cowboy has often been “falsely imagined,” “greatly despised,” and “little understood.” Nevertheless, cowboys exhibited many exceptional qualities: pride, honesty, hard work, tolerance of pain, and courage, which one dandy sneered at as a “somewhat primitive code of honor.”

Perhaps the negative view of cowboys in the early days finds its genesis in the origin of the word itself. In America, the word was first used during the Revolutionary War when a group of New York Tory guerrillas, who were called cowboys, roamed the countryside of Westchester County. It’s likely the expression for these British-loving “cowboys” was borrow from English satirist Jonathan Swift, who was the first to use the term in print in his 1730 poem, “A Panegyric on the Dean in the Person of a Lady in the North.” Neither Swift nor the New York Tories used the term in conjunction with herding or tending cattle. In the mouth (or pen) of an Englishman the word cowboy was usually a derogatory description for a reckless or careless individual, one who was often a swindler, scoundrel, rogue, or rascal.

The next group of men called cowboys lived up to the characterization of wild-riding rascals. Another name for them was Texan. Shortly after Texas won its independence and became a Republic, these “cow-boys,” under the leadership of Ewen Cameron, spent their time chasing longhorns and Mexicans, who saw these men as the symbol of calamity.

Mexicans attitudes notwithstanding, the term cowboy as we understand it today—a man who works with cattle and horses all or part of the year as a salaried ranch hand—comes from the Spanish vaquero: vaca (cow) and the suffix ero, meaning “one engaged in working with cattle.”

As a whole, cowboys are little interesting in the etymology of the title they so proudly wear. But this isn’t to say they aren’t interested linguistic pursuits, especially when it comes to inventing names for each other.

Slang Terms for Cowboy

Cowboy lingo is rich in comic character. It is both picturesque and pungent, highlighting a cowboy’s activities, disposition, and experience. The terms he uses for himself and his fellows is no different.

Caballero is Spanish for horseman. Literally, this translates to cavalier or knight, but when used of cowboys it refers to a man who demonstrates a reckless, indifferent, or devil-may-care attitude—especially a-horseback.

Corrida is another Spanish term. This one means expert or artful. It’s from the verb correr, meaning “to run,” thus to cowmen, a corrida is an expert (or artist) who runs cattle.

Cowhand is a general term for cowboy, and the one cowboys most often use when referring to one of his profession. Sometimes this is shorten to hand. On occasion, you’ll hear cowboys refer to a particularly expert or skilled cowboy (or corrida) as a top hand, who also goes by ranahan or ranny (for short).

Cowpuncher is a popular term for cowboy. It’s derived from a pointed metal prod or pole used to urge cattle into boxcars. It’s often shortened to puncher—one who punches or herds cattle. Similar terms are cowpoke and cow prod.

Heel Squatter is not necessarily a cowboy’s favorite alias, but illustrative of the common practice of resting or eating by squatting on the boot heals. Occasionally, he’s also called a frog squatter, since he looks like a frog ready to leap from his heels.

Horseman is a universal term applied to any man mounted on a horse who’s skilled in horsemanship, whether cowboy or wrangler (who herded horses on cattle drives). In the Southwest he might be called a jinete, from the Spanish, meaning rider.

Light Rider is a cowboy who sits effortlessly in the saddle, keeping himself in balance with the horse. He can ride long distances without retightening the cinch or galling the horse’s back, no matter the man’s weight.

Ranchman is a general term for anyone connected with the running of a ranch, whether ranch owner or boss (the employer) or cowhand (the employee).

Saddle Slicker describes exactly what happens to a cowboy’s saddle after years of riding. Related terms just as descriptive are saddle stiff, saddle warmer, and leather pounder.

Three-up Screw is a cowboy woking a small ranch where three horses are considered enough for a mount.

Waddy (sometimes spelled waddie) is an unusual term for a cowboy. The exact origin is unknown, but could be derived from the word wad, something used to fill a gap. Ranches were sometimes short-handed in the spring and fall, so ranchers hired anyone who could fork a horse for a few weeks to fill in the gaps until more seasoned cowboys hired on. In those cases, ranches were know to be wadding their outfits.

All the idioms we’ve see thus far are generally positive and are applied to experienced cowboys. With such a variety of expressions for the professional, you can bet the ranch they have a passel of terms and phrases to describe the amateur.

Advertising a leather shop is a colorful description for a man who dressed in exaggerated leather boots, chaps, vests, and cuffs, looking, as the expression went, “like he was raised on the Brooklyn Bridge.” This man was also called a mail-order cowboy, Monkey-Ward cowboy (for the Montgomery Ward department stores), or skim-milk cowboy. Theodore Roosevelt fit this bill when he first arrived in the Badlands of North Dakota, dressed as he was in his tailored leathered tunic and breeches, and Tiffany made knife.

Arbuckle refers to a brand of coffee that was so common on trail drives it was considered the “cowboy’s coffee.” In reference to inexperienced men, an Arbuckle alludes to the stamp or coupon printed on bags of coffee. Cut out, these coupons could be redeemed for merchandise—like Green Stamps, for those old enough to remember. The company issued catalogs of goods with the corresponding number of coupons need to “purchase” that item. For example, twenty-five stamps were needed for an apron, twenty-eight for a razor, and forty for a pocketknife. A particularly thirsty cowboy could redeem 150 coupons for a double-action revolver. Since the cash value of each coupon was worth one cent, an Arbuckle cowboy was one “redeemed” on the cheap.

Bootblack Cowpuncher was an Easterner who came West in the hopes of making money in the cattle business. Again, TR would have fit this description. This man was also known as a Johnny-come-lately, pilgrim, or shorthorn (which is also slang for Hereford cattle).

Other terms for inexperienced cowboys were early bouten (a Dutch term for “fart”), flat-heeled peeler (sometimes used of a farmer turned cowboy), greener, greenhorn, green pea, lent, new ground, pistol, punch, and tenderfoot. Stringin’ a Greener is to play a good natured trick on an unseasoned man.

Regional Names for Cowboy

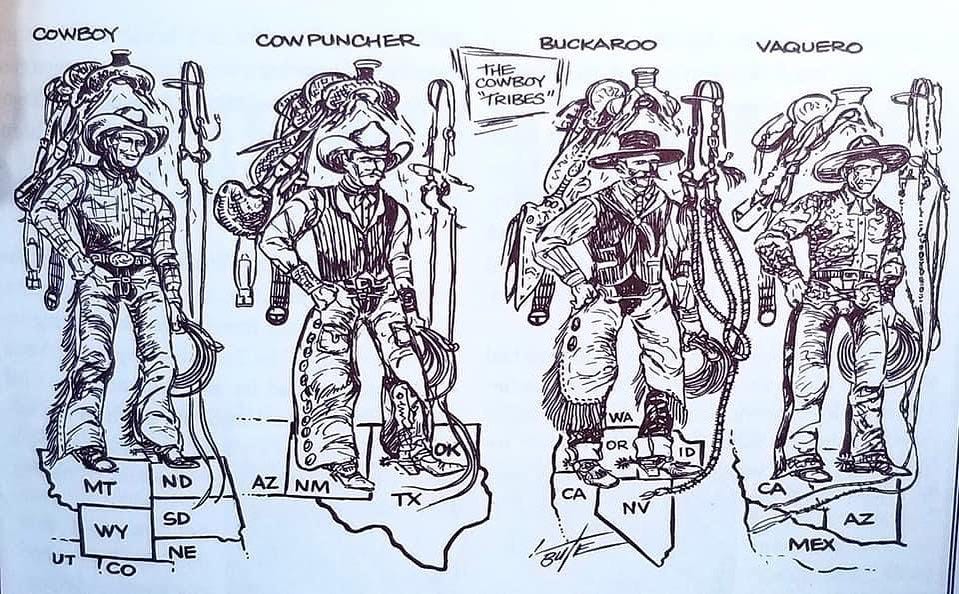

Generally, cowhand was the preferred term cowboys used for each other. But they would employ regional names for a cowboy if known and appropriate.

Brush Hand is a cowboy from the brush country, usually South Texas.

Buckaroo is the preferred term for cowboys in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Nevada. The word is Anglicized from vaquero or boyero. Related terms are baquero, buckhara, and buckayro. Sometime, though rarely, jackaroo is used.

Hillbilly Cowboy is a man working for an outfit whose range is pretty well out in the sticks.

Rawhider is a general name northern cowboys called Texas cowboys.

Tullies are men or cattle native to yucca (tules) country of the Southwest and California.

Vaquero was typically applied to mestizos cowboys—mixed descendants of Spanish and Indian blood—who originally worked for Mexico’s missions and haciendas.

Speciality Terms for Cowboy

By now you’d think cowboys would have spilt the banks of the English language when it comes to naming each other. Not so. They were living dictionaries of terms and phrases, especially when it comes to word paintings for those who exhibit special skills.

Bog Rider is a cowboy whose job is to rope mired cattle and pull them to dry ground. He usually rides a stout horse and carries a short-handled shovel to free the legs of struck cattle. Bog riders usually rode in pairs. They’re also known as pothole riders.

Bronc Buster, as the name implies, is a man who breaks wild horses, gentling them for use as cow-horses. Old timers use to say these men had “a heavy seat and a light head.” Other names for this cowboy is bronc peeler, bronc scratcher, bronc snapper, bronc squeezer, bronc stomper, bronc twister (or twister), bull-bat, buster, peeler, and rough-string rider.

Brush Buster is an expert at running “cactus boomers” out of underbrush, like mesquite, where cattle like to hide. He had to be a very good rider since he had to hold his seat in various position while dodging thorns and limbs. His dress and equipment is different from the romantic notions we have of the cowboy. His hat is short brimmed, his chaps are smooth and form fitting—what are usually known as shotguns—his jacket is tight, short, and made of canvas, his gloves (if he wears them, though many didn’t, claiming “it’s cheaper to grow skin than buy gloves”) are tough and unadorned, and his saddle is simple and smooth, with heavy bull-nosed tapaderos coving his stirrups to protect his feet. He not only has to be a tough man, but a courageous one. Other names for this cowboy are brush popper (“The most popular name for the brush hand. He knows he would never catch a cow by looking for a soft entrance; therefore, he hits the thicket center, hits it flat, hits it on the run, and tears a hole in it.”), brush roper (“It took just two things to make a good brush roper, especially at night—‘a damned fool and a race horse.’”), brush thumper, brush whacker, and limb skinner.

Bull Nurse was a cowboy who accompanies a shipment of cattle on a train to their ultimate destination.

Chuck-line Rider could have a positive or negative connotation, depending on the man. Sometimes cowboys were between jobs and had to rely on the hospitality of ranches for food and shelter. Whenever a man was reduced to doing so he was said to be riding the bag-line, riding the chuck-line, or riding the grub-line. Professional cowboys always worked for their meals and board, even if a full-time job wasn’t offered or available. Other men who wouldn’t or couldn’t secure a settled job with an outfit or ranch rode the range taking advantage of the hospitality offered without the intention of earning his keep. These men were considered professional chuck-line riders and were despise by all honest cowboys. Another term for this man, whether good or ill, was grub-line rider.

Circle Rider is a cowboy, working in pairs, who rides wide circles to roundup cattle and drive them to a designated holding spot.

Contract Buster is a professional, but freelance, bronc buster who usually travels to smaller ranches that can’t afford a full-time buster to break their horses. He’s routinely paid by the head. He’ll ride anything with hair on it—for a price.

Cow Nurse is a cowboy who looks after sick or crippled cattle, which are kept in a separate herd.

Cutter is a cowboy whose job is to cut out cattle, to separate individual cows from the herd. It also refers to the man who cuts identification earmarks on the cattle during branding.

Dally Man works horseback in a corral during roundup, roping calves, dallying the end around the saddle horn, and dragging them to the branding fire.

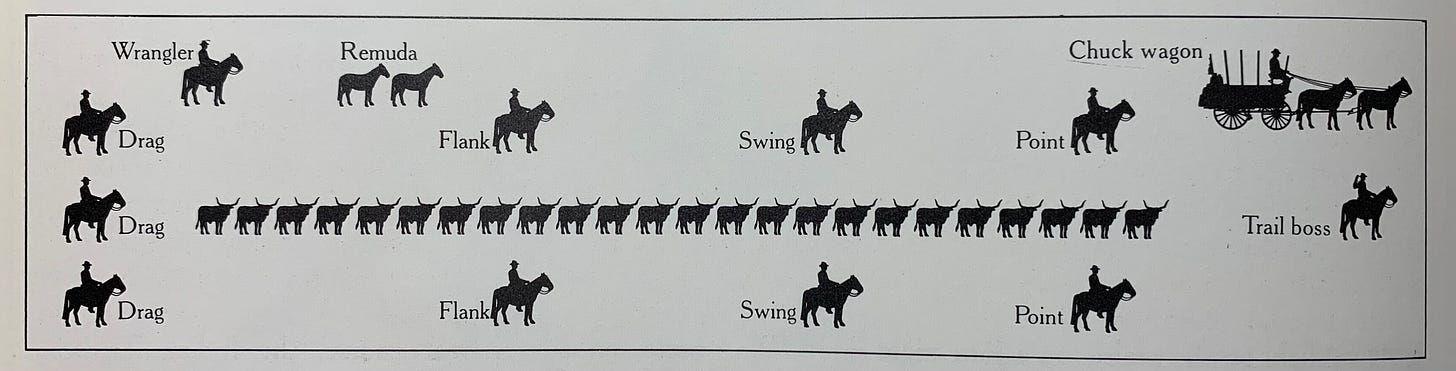

Drag Rider was one of the lowest jobs on a cattle drive since he was required to ride behind the weakest and laziest cattle (the drag) to keep them moving. On dry, dusty days, if he wasn’t careful to keep his nose and mouth covered by his neckerchief, he would eat his weight in trail dust. He’s also known as the tail rider.

Flank Rider was a cowboy who rode on either side of the column of cattle on a drive. They rode about one-third of the distance of the column behind the swing riders, roughly two-thirds the distance behind the point riders

Flash Rider is a bronc buster who takes the first rough edges off unbroken horses. On a cattle drive, gentling these horse would be finished on the trail.

Gate Horse refers to any cowboy stationed at the corral gate.

Hold-up Man was often applied to a robber of stagecoaches, trains, or banks, but applied to a cowboy it points to a man positioned at a crossroads, on a hill, or other critical juncture to keep herded cattle from leaving the trail.

Lead Man was also known as the point rider. He rode at the head of a column of cattle being herded up a trail. Typically, there were two lead men, one on either side of the column. This was the honored position on a cattle drive and the station of greatest responsibility, since these men determined the direction taken and pace of movement. As a result, this post was reserved for top hands.

Line Rider was a cowboy who rode over his employer’s ranch assessing the condition of fences, cattle, watering holes, and grazing land. His job was to repair, doctor, or move whatever was necessary.

Mavericker describes a man who rode the ranges looking for unbranded (“maverick”) cattle. At the beginning of the cattle industry in Texas, roping and branding any calf not following a cow wasn’t considered stealing, but legitimate thriftiness. Calves of this kind were considered unclaimed and available for any cowboy to slap a band on.

Miller is a man hired on a ranch to tend windmills. He’s also known as a mill rider, windmiller, or windmill monkey.

Outrider performed a job similar to that of the line rider, but unlike that man, the outrider was commissioned to ride outside of his employer’s ranch looking for strays.

Outside Man was a top hand who represented his employer’s brand at general roundups. He was a riding encyclopedia of brands and earmarks, able to identify cattle belonging to his outfit in a vast and milling herd. Once his outfit’s brand or earmark was discovered, he cut his cattle out and returned them to his ranch.

Renegade Rider was a cowboy employed to visit ranches, sometimes as far away as fifty or more miles, to pick up stock marked with his employer’s brand.

Swing Rider was a cowboy who rode on either side of the column of cattle on a drive. They rode about one-third of the way behind the point riders.

Tally Hand is a man selected to keep a record of calves branded at the spring roundup. He’s chosen because of his honesty and clerical ability. Usually he’s an older man who’s physical inability to perform more strenuous work like flanking, holding, or branding calves. He’s also known as the tally man.

Trail Driver was a cowhand engaged in driving cattle over long trails, typically over one of the interstate trails from Texas. The most common designation is trail hand.

White-water Bucko is an expert at crossing cattle across rivers.

Negative Names for Cowboy

In the popular mind today, cowboys enjoy a near mythical status of good will. But, as mentioned, that wasn’t always the case. It never was among the outlaw class—then or today—nor among sheepherders.

Bucket Man was a contemptuous name given to honest cowboys by rustlers. Rustlers also called these men pliersmen (because they work on fenced ranches), saints, and sheep-dippers.

Gunnysacker was a derogatory term used by sheepmen for cowboys, who use to raid sheep camps wearing gunnysacks over their heads during the sheep wars.

Knothead is a belittling term used by experienced cowboys for inexperienced cowboys who never attain the necessary skills to be a top hand. Another name is scissor-bill. (Knothead can also refer to an unintelligent horse.)

Phildoodle is similar to a mail-order cowboy, but this man has no intention of becoming a real cowboy. He’s merely a drugstore cowboy—one who imitates a cowboy in dress and speech.

Pumpkin Roller is a term of derision for any cowboy who complains, grumbles, or is an agitator, since they give cowboys, who by nature are uncomplaining and easy going, a bad reputation. Sometimes this man might be called a freak.

Sooners is usually used of Oklahomans in general, but in cowboy culture it refers to men who rode the range branding maverick cattle before the date set by the official roundup association.

Ramon Adams, one of the most renowned experts on cowboy culture—his lingo, humor, and life—offers an evocative summary of the cowboy’s title and character:

A generation ago the East knew him as a bloody demon of disaster, reckless and rowdy, weighted down with weapons, and ever ready to use them. Today he is known as the hero of a wild west story, as the eternally hard-riding movie actor, as the “guitar pickin’” yodeler, or the gayly bedecked rodeo follower.

The West, who knows him best, knows that he has always been “just a plain, everyday bow-legged human,” carefree and courageous, fun-loving and loyal, uncomplaining and doing his best to live up to a tradition of which he is proud. He has been called everything from a cow poke to a dude wrangler, but never a coward. He is still with us today and will always be as long as the West raises cows, changing, perhaps, with the times, but always witty, friendly, and fearless.

Notes:

“I don’t expect to get to Belle Fourche”: The Cowboys, dir. Mark Rydell, (2007; Burbank: Warner Brothers Studio, 1972), Blu-ray. A. Martinez’s character, Cimarron, a drifter of “mistaken nature” is somewhere between the ages of eighteen and twenty, but isn’t one of the schoolboys and is hired later on the drive. The only other “man” on the drive is the cook, Jebediah Nightlinger, portrayed by the wonderful Roscoe Lee Browne, who delivers some of the best lines in the film—particularly the story of this father, the “brawny Moor,” and his confession just before his hanging.

synonymous with cowboy: “For the Pawnee, a cowboy or any man who works with cattle is simply known as téksis.” Matthew Kerns, Texas Jack: America’s First Cowboy Star (Guilford: TwoDot, 2021), 78.

“The cow-boy.—the Cowboy!”: John B. “Texas Jack” Omohundro, Jr., “The Cowboy,” Wilkes’ Spirit of the West, March 24, 1877, republished in the show pamphlet Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (London: Allen, Scott & Co., 1887), 20.

“somewhat primitive code of honor”: John Baumann, “Experiences of a Cow-Boy,” Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, vol. 38, July–December, 1886 (Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott Company, 1886), 315.

Perhaps the negative view of cowboys: I recently heard it claimed the term cowboy was a derogatory word white Texans invented in the 1860s for newly freed black slaves who worked cattle. The expression, as the assertion has it, found its origin in the disparaging and racist term boy—as in, “Boy, go rope that cow.” Not so. The term cowboy can be traced back to AD 1000 in Ireland. From the 1820s to 1850s, in Britain, the related term cowherd was used to describe young boys who tended cattle.

In America, the word cowboy was first used during the Revolutionary War: The Oxford English Dictionary (1785) defined a cowboy as “a contemptuous appellation applied to some of the Tory partisans of Westchester County, N. Y.”

“A Panegyric on the Dean in the Person of a Lady in the North”: Jonathan Swift, “A Panegyric on the Dean in the Person of a Lady in the North,” The Works of Jonathan Swift, vol. 15 (London: Bickers & Son, 1883), 176.

Another name for them was Texan: In Norway, “Texas” means “wild” or “crazy,” as in det var helt texas, which translates, roughly, “it was totally/absolutely/completely wild/crazy/bonkers.” The etymology goes something like this: “Texas” = “cowboys” = “Wild West” = “an unpredictable, exciting, sometimes scary atmosphere.” See Dan Solomon, “Y’all, Norwegians Use the Word ‘Texas’ as Slang to Mean ‘Crazy,” Texas Monthly, October 20, 2015.

Shortly after Texas won its independence: See John Solomon Ford, Rip Ford’s Texas, ed. Stephen B. Oates (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991).

redeem 150 coupons for a double-action revolver: See Anne Cooper Funderburg, “Cowboy Coffee,” True West, July 1, 2001.

originally worked for Mexico’s missions and haciendas: One of the best pieces I’ve read on the history and tradition of vaqueros was written by Katie Gutierrez, “The Original Cowboys,” Texas Highways, September 2021.

“The most popular name for the brush hand”: Ramon F. Adams, Western Words: A Dictionary of the Old West (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1998), 21.

“It took just two things to make a good brush roper”: J. Frank Dobie, A Vaquero of the Brush Country (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1957), 200.

“A generation ago the East knew him as a bloody demon of disaster”: Adams, Western Words, 41.

Second pass: Agree with your notes on The Cowboys on Brown's Nightlinger character. Best lines! The short, blank verse ending something like "but I just don't have the time" is still a tickler.

I've somehow heard Cimmaron's description "mistaken nature" as a half mumbled "mistake of nature" all this time. Thanks.

Blood touching blood set me back on one. I had to stop to look up three-bell mule. Fascinating.