Juan Seguín Buries the Hero Dead of the Alamo

Texas shall be free and independent or we shall perish in glorious combat.

Juan Seguín

It is an unfortunate and inexcusable fact that the heroism of the Tejanos during the Texas Revolution have received so little recognition and praise. It is highly doubtful that without their determination, courage, and sacrifice—known and unknown—Texas would have ever become an independent republic. Men like Juan Abamillo, Juan A. Badillo, Carlos Espalier, Gregorio Esparza, Antonio Fuentes, Jośe María Guerrero, Damacio Jimenes (Ximenes), Toribio Losoya, and Andrés Nava, who died at the Alamo,1 Lorenzo de Zavala, Jośe Antonio Navarro, and Jośe Antonio Menchaca, who survived the revolution, as well as nameless others who foraged an independence nation out of tyranny.

One of the most famous Tejanos during those heady days of struggle was Juan Nepomuceno Seguín. By the time the revolution began, the Seguíns had been in Texas for almost a hundred years, establishing a family presence sometime in the 1740s. The family prospered and became large landholders, include a nine-thousand-acre ranch a day’s ride south of San Antonio where they raised cattle. The headquarters was a castle-like hacienda fortified against Indian attack known as Casa Blanca. Juan’s father Erasmo had served as alcalde (mayor) of San Antonio and was an early supporter of Anglo colonization through his friendship and encouragement of Moses Austin, Stephen F. Austin’s father. After Moses’s death, Erasmo accompanied Stephen across the Sabine and helped him carry on his father’s work. Juan was a just boy. But by the time the first shots of the revelation were fired, Juan had served as the alcalde of San Antonio and was el jefe político of Béxar—the highest ranking political administrator in the Mexican department of that region.

During the revolution Seguín was awarded the rank of Captain, serving as a scout for Austin in 1835 during the siege that dislodged Mexican General Martin Perfecto de Cos from the Alamo. A year later, when Travis, Bowie, and Crockett were holdup in the Alamo, Seguín and at least fifteen other Tejanos were with them within the walls. In late February he slipped out of the Alamo with a message for Sam Houston and an urgent plea for the commander of the forces at Goliad, James Fannin, to come at all hast to the aid of the besieged defenders in the Alamo. Seguín rode back but before reaching San Antonio the mission-fortress had fallen and all the defenders were dead.

Seguín and his Tejano cavalry company of twenty then served as a rear guard to Sam Houston’s army during the eastward retreat that became known as the Runaway Scrape. At San Jacinto Seguín was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. He and his cavalry served as the only organized Tejano company during the battle. Houston ordered them to place playing cards in their hat bands so they wouldn’t be confused with Mexican soldiers who might try to disguise themselves. Seguín and his men distinguished themselves during the eighteen minute battle which secured independent for Texas.

During the years of Republic, Seguín served in the Texas senate. Eventually, however, he would go into exile in Mexico and even fight against this brother Texans after the debacles of the Santa Fe Expedition and the Vásquez invasion. He was later accepted back into Texas and became a justice of the peace.

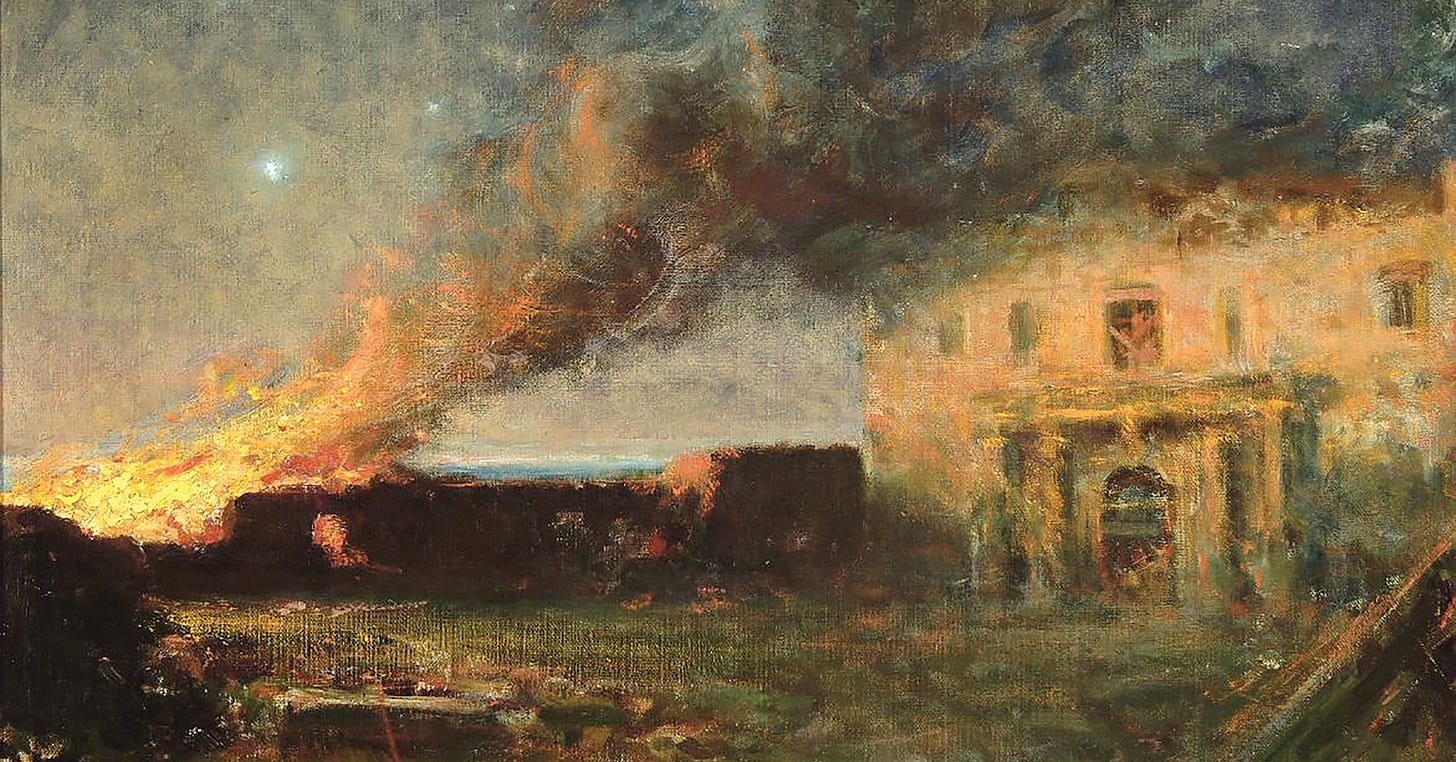

On February 25, 1837, Seguín led a formal military burial detail to inter the ashes and bone fragments of those who died at the Alamo, after Mexican president and general Antonio López de Santa Anna had the bodies burned on funeral pyres.2 What follows are Seguín’s remarks that day, as they appeared in the Columbia (Houston) Telegraph and Texas Register on April 4. Seguín speaks from one of the reputed spots where the bodies were incinerated.

Companions in Arms!! These remains which we have the honor of carrying on our shoulders are those of the valiant heroes who died in the Alamo. Yes, my friends, they preferred to die a thousand times rather than submit themselves to the tyrant’s yoke. What a brilliant example! Deserving of being noted in the pages of history. The spirit of liberty appears to be looking out from its elevated throne with its pleasing mien and point to us saying: “There are your brothers, Travis, Bowie, Crockett, and others whose valor places them in the rank of my heroes.” Yes soldiers and fellow citizens, these are the worthy beings who, by the twists of fate, during the present campaign delivered their bodies to the ferocity of their enemies; who, barbarously treated as beasts, were bound by their feet and dragged to this spot, where they were reduced to ashes. The venerable remains of our worth companions as witnesses, I invite you to declare to the entire world, “Texas shall be free and independent or we shall perish in glorious combat.”

Colonel Juan N. Seguín

Commandant San Antonio, Bexar, Texas

Army of the Republic of Texas

This represents the Tejano Alamo dead compiled from the Daughters of the Republic of Texas. The list complied by Thomas Ricks Lindley in his Alamo Traces disputes the inclusion of some names on DRT’s list, including that of Jośe María Guerrero.

The actual location(s) of the final resting place(s) of the Alamo defenders’ ashes and bone fragments is difficult to determine with any accuracy or certainty. Within the nave of the San Fernando Cathedral, a few blocks west of the Alamo, sits a sarcophagus. A plaque claims the sarcophagus hold the remains of the Alamo dead. Some sources maintain that the remains are buried at the Odd Fellows cemetery in East San Antonio. All we can say for certain is that the bodies were burned on funeral pyres just south of the Alamo. Bones not scattered by animals or ashes blown away in the intervening year of 1836 and 1837 were gathered and buried somewhere in San Antonio. Probably some (if not all) are interred within the walls of the San Fernando Cathedral.