Chuckwagons and Biscuit Shooters

The roads on this rough and colorful range were ground into being by [the chuckwagon’s] broad-tired wheels, engineered by the wagon cook and his four-mule teams.”

J. Evetts Haley

It’s doubtful the golden age of the cowboy, which lasted just a little over a decade (roughly from 1867–1881), and was marked by driving cattle up one of the many trails from Texas to Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana, would have occurred if it wasn’t for the chuckwagon—the nineteen-century’s food truck. In it a cattle outfit carried everything necessary to feed, doctor, and accommodate a crew of ten or more for months on the open range without resupply.

Howdy, folks. If you’re reading this from a post off social media, or a friend shared this with you, welcome. Pull up a chair, put your boots up, and stay awhile—and consider becoming a subscriber. If you’re already a subscriber, and like what you read, think about becoming a partner to keep Y’allogy going and growing by upgrading as a paid subscriber. But whatever y’all choose to do, I’m much obliged y’all are here.

A Brief History of the Chuckwagon

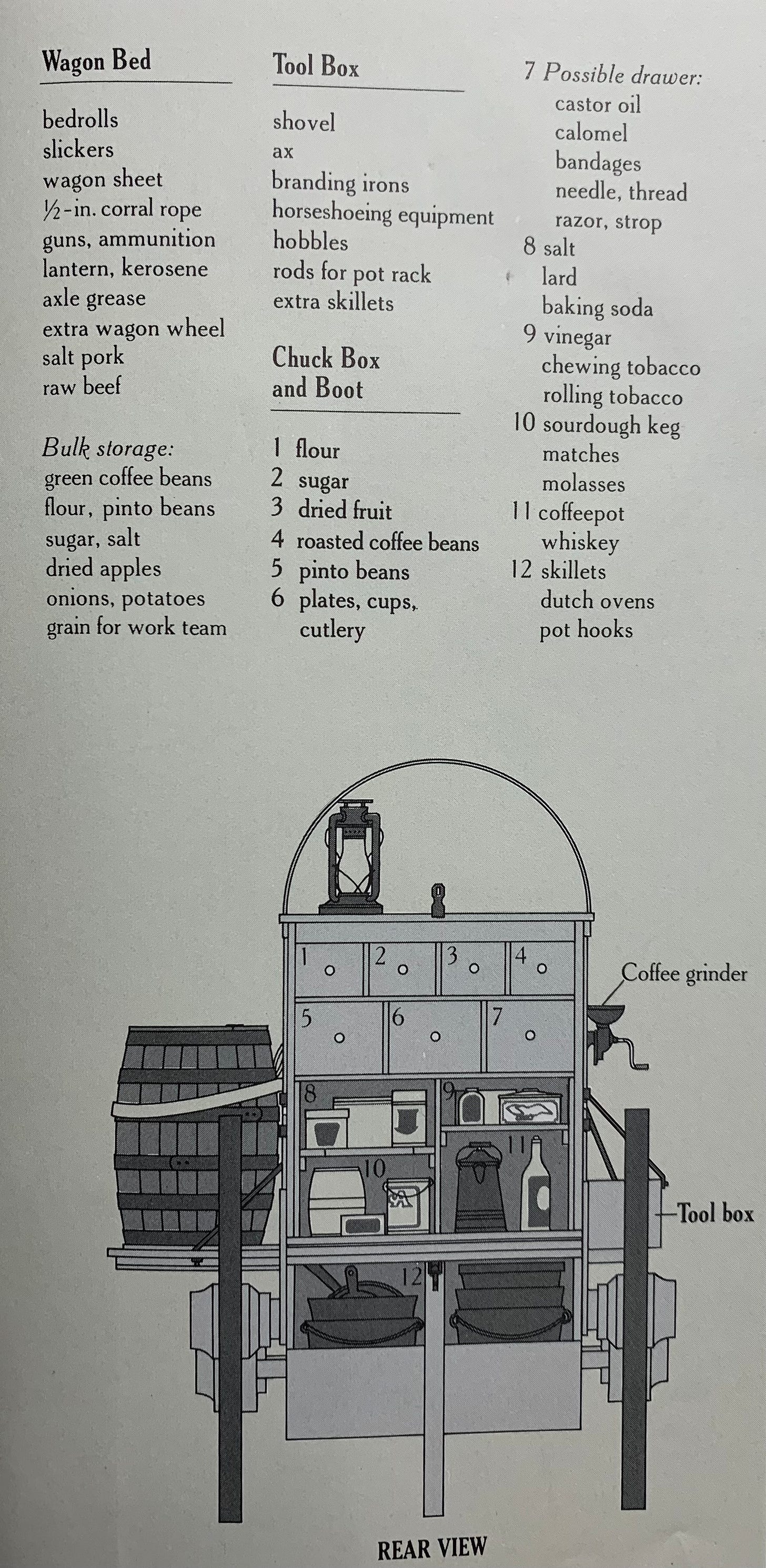

The first chuckwagon was invented cattleman Charles Goodnight, who in 1866 bought a surplus Army wagon and refitted it to meet the needs of a trail drive. He dragged the wagon to a carpenter in Parker County, Texas and had it rebuilt out of the toughest wood available: seasoned bois d’arc. He removed the wooden axles and replaced them with iron, and exchanged the tar bucket with a can of tallow for greasing. On one side he placed a platform for a barrel large enough to hold two days’ supply of water. On the other side he constructed a heavy toolbox to accommodate a hand hammer and sledge hammer, an axe and shovel, branding irons, horseshoeing equipment, and rods for a pot rack. Stake poles, used for picketing “night horses,” were strapped along the side. The bed of the wagon was lined with curved wooden bows, over which a heavy canvas was stretched for protection against sun and rain.

Bolted on the rear of the wagon was the chuck box, which looked similar to a Victorian desk: honeycombed with with drawers and cubbyholes where the cook storied food staples such as coffee, beans, cans of salt, sugar, soda, molasses (or “lick”), lard, and other food items, as well as eating utensils—tin plates, tin cups, and cutlery. There was also space for other necessities: medicinal supplies (including whiskey), needles and thread, razor and strop. The chuck box was covered by a hinged and locking lid. While in motion, it kept the drawers and cubby holes closed. While in camp, it was lowered, supported with a swinging leg, creating the cook’s worktable and cutting board.

Underneath the chuck box was the “boot,” another large box that held the cook’s dutch oven, pots and pans, and skillets. It too was covered by a lid while traveling and opened while in camp.

Inside the bed of the wagon the cook carried a large amount of four, bacon, extra sugar and pinto beans, dried fruit, cases of canned goods (or “airtights”) like peaches and tomatoes, a reserve supply of “lick,” and probably a jar of sourdough starter for sourdough biscuits. Grain for the horses and mules was usually stored beneath the springed driver’s seat.1

When available, cooks carried cans of condensed milk, what the cowboys called, “canned cow.” It was a particular favorite. In their evocative way, cowboys like to say, “No tits to pull, no hat to pitch. Just punch a hole in the son of a bitch and drink.”

The cook also kept beef in the wagon bed. J. Evetts Haley wrote, “A fresh beef was killed when needed, usually in the late afternoon, quartered, and hung alongside the wagon or between the spokes of the wagon wheel. The cool night of the High Plains chilled the meat, and immediately the next morning it was wrapped in a tarp or in slickers and placed at the bottom of the wagon. Bed rolls were thrown in upon it to help shut out the noonday heat, and the meat would usually keep fresh for several days. Each night the operation was repeated, and usually by the third day the beef, a sucking calf, had been eaten and another was killed.”2

Some cooks slung a beef hide under the wagon, called a cuña (cradle), to carry extra wood the wranglers or cowboys gathered while tending horses or cattle. Outfits heading up the Chisholm Trail or the Western Trail passed through Indian Territory and onto the tree-sparsed plains of Kansas where firewood was chancy. Cooks would then sometimes hitch a two-wheeled wagon known as the “chip wagon” to the back of the chuckwagon. The “chip wagon” held enough cow and/or buffalo chips to prepare at least three meals. Properly fanned, chips made a hot fire. Hot enough to quickly boil a pot of coffee—though it took a considerable amount of chips to cook a skillet of biscuits.3

The Authority and Reputation of Trail Cooks

Cowboys had colorful names for trail cooks: “Sheffi,” “Dough Roller,” “Dinero,” “Coocy,” “Bean Master,” “Pot Rustler,” “Dough Puncher,” “Grub Slinger,” “Coosie” (from the Spanish for cook, cocinero) and “Biscuit Shooter.” But whatever you called him, next to the trail boss, the cook was lord of the rolling manor. Everyone, trail boss included, walked gingerly around the chuckwagon and pharisaically followed the unwritten etiquette that governed the cook’s sovereign domain.4 On more than one occasion, cowboys who walked between the cook fire and the chuckwagon, failed to roll his bed and place it in the wagon, put his tin cup or tin plate on the chuck lid instead of in the round pan or wreck pan—the tub for washing dishes—or stirred up a dust cloud while the meal was being prepared received at the very least an unrestrained profanity-laced tongue lashing, and perhaps a “leggin’s case,” where the cowboy was held over a barrel and whipped with a pair of chaps.

Ill-tempered cooks could be cantankerous autocrats and could ruined the morale of a cow camp with just a look. On the hand, good-humored cooks always improved it. Trail hands took pains to stay in his favor—not only to avoid leggin’s, but also to receive candy. Coffee was a staple on the trail, but had to be hand ground. One favorite brand was Arbuckle’s, which included a peppermint stick in every one-pound bag. When the cook hollered, “Who wants the candy?” some of the toughest cowboys ever to fork a horse fought for the privilege of cranking the grinder.

On the trail, cooks did more than cook. They also packed, drove, and repaired the wagon, built fires, doctored cuts (sometimes with kerosene oil), set broken bones, pulled teeth, sewed buttons, cut hair, and settle bets. But the quality of his cooking was paramount. In fact, how well a cook cooked (or couldn’t cook) could make or break a trail drive. Cowboys were known to join outfits or quit outfits based on nothing else than the quality of the grub.

A Day in the Life of a Biscuit Shooter

On the drive (or at roundup) the chuckwagon was the center of a cowboy’s universe. Not only was it the place where he came to eat, drink a dipper of water, or get doctored, it was the place where every cowboy threw down his bedroll for the night, usually in a semicircle around the cook fire.

Cookie was the first man up in the morning, the busiest man throughout the day, and the last man, save the night herders, to bed at night. Every morning before dawn, he started a fire with whatever fuel was available—wood, cow or buffalo chips—and worked his sourdough into biscuits. All the while the wrangler was rounding up the remuda—the horse herd used by the cowboys. In no time, the cook had a large pot of coffee boiling and breakfast of biscuits and bacon ready. He yelled out, “Chuck,” “Come and get it,” or “Wake up snakes, and bite a biscuit.” Cowpunchers rolled out of bedrolls putting on their hats and boots—always in that order—and lined up for their share of coffee and “chuck.”

After breakfast, but before mounting up, cowboys secured their bedrolls and threw them into the wagon. The cook washed cups and plates, scrapped the bacon grease from the skillet with whatever was on hand—sage brush or grama turf—doused the fire, packed his wagon, harnessed his four-mule team and move ten or twelve miles further up the trail, reestablishing camp (which was moved almost every day, sometimes twice a day).

Most trail bosses, to ensure their hands work efficiently, placed the chuckwagon ahead of the herd, not behind it. After breakfast at 4:00 every trail hand looked forward to dinner, the noonday meal. But they had to keep driving the herd until they reached the place where the cook set up camp. In the evening, if the cook became lost while passing through unknown country, he never worried. He stopped his wagon and established camp, making himself at home, certain that every cowpuncher in the crew would track him down since he had their bedrolls and carried the evening’s meal.

At a new camp, the cook and hoodlum, if one was on the drive, tossed the beds out of the wagon, staked out the wagon canvas to create a canopy over the chuck lid, and dug a pit for the cook fire. Then he prepared the meal, as Haley described it:

Coosie sets his coffee pot on the flames, pulls a quarter of beef from the cool depths of the wagon, and slices it into steaks; he places dried fruit to stew; a skillet of grease to heat, empties a third of a sack of four into a dishpan, hollows the center, and pours in a gallon of fragrant sour-dough. He . . . throws in a fistful of baking powder, a pound or so of lard and the other essentials, and dives into the bubbling white mass with a right good will.

Haley then says, “While some cooks are as meticulous and clean as any old maid, others seem to know the virtue of soap and water only in a distant sort of way.” Did that matter to hungry cowboys? Not at all. “For when [cooks] wipe their hands on the seats of their breeches, straighten up from over the coals and roar their welcome ‘Chuck,’ every mother’s son stampedes for the box like a bunch of wild [mustangs] for the open range. And whether their steaks are perfect, or their biscuits squat to raise and bake on the squat, [cow cooks] are unquestioned bosses of the camps as though to the manor born, and woe to the man who transgresses their prerogatives.”5

After the evening meal, and cleaning up, before the cook turns in for the night, he locates Polaris—the North Star—and turns the chuckwagon tongue in that direction. The next morning after breakfast, the cow crew, finding their bearings to true north, set the cattle up the trail. And the cook starts another day afresh.

Because of its practicality, Goodnight’s chuckwagon became widely popular. Cattle outfits across the West began imitating it, refitting farm wagons and Army wagons. In time, chuckwagons were commercially built and sold for anywhere between $75 and $100. The two largest commercial builders were the Studebaker Company, from South Bend, Indiana, and Peter Schuttler Company, from Chicago, Illinois.

J. Evetts Haley, The XIT Ranch of Texas and the Early Days of the Llano Estacado (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1977), 151.

Rarely on cattle drives, but not unusual during roundups, a second wagon carried firewood, water barrels, poles, extra bedding, and other necessary supplies. This wagon was known as the “hoodlum wagon,” and the man who drove it was called the “Hood.”

Back at the ranch, foremen and hands all bowed to the cook, giving him deferential treatment, especially when entering the cook shack, which also doubled as his sleeping quarters. He was too important a man to be considered just another hand, required to bed down in the bunkhouse.

J. Evetts Haley, Charles Goodnight: Cowman and Plainsman (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959), 403–4.