Books I Read in 2024

Not just a list of books, but a little critique as well

Y’allogy is 1836 percent pure bred, open range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. Texan is spoken here. I’d be much obliged if you’d consider riding for the brand as a free or paid subscriber. (Annual subscribers of $50 receive, upon request, a special gift: an autographed copy of my literary western, Blood Touching Blood.)

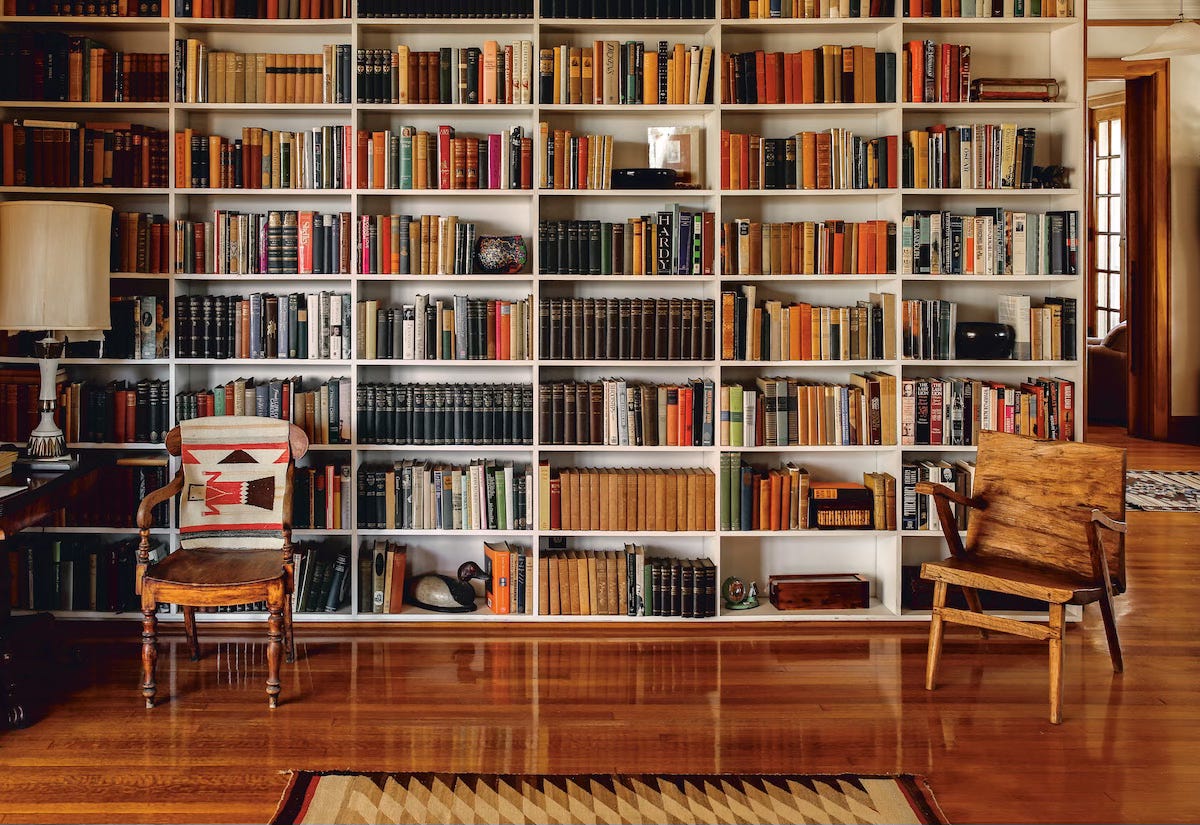

However large his own library may be, every other man’s library is an object of curiosity to him for the strange and unknown wonders it may possess.

Walter Besant

For the past decade or so I’ve kept a list of books I’ve read each year. I’ve published those lists hoping something therein might pique someone’s interest for the coming year. The cumulative number of books is sizable—at least for me.

In year’s past I’ve merely published the books in the order I read them—their titles and authors. That’s it. But not this year. This year I’m doing something different. My friend Joel Miller, who publishes a wonderful newsletter about books and reading, persuaded me that a simple list is, well, boring. What I ought to do instead is provide a short summary and review of each book. Alright, Joel, challenge accepted.

What you’ll find this year is the list of books I read in 2024—for pleasure, not those I read for my work as a ghostwriter—along with a sentence or two (or three) of my thoughts about each. Perhaps you’ll find something to whet your appetite for 2025.

Happy New Year, y’all—and happy reading.

The Lamentable Tragedy of Titus Andronicus, William Shakespeare

“Artistic ugliness. Beautiful violence.” That’s how I opened my review of Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian. After reading McCarthy, I had thought no piece of literature could be as grotesque and exquisite in equal measure within the covers of one book. That is, until I read Shakespeare’s first tragedy, Titus Andronicus.

Oath and Honor: A Memoir and a Warning, Liz Cheney

January 6, 2021, was one of the darkest days in American history—certainly within the last half century. The events of that day have become polarized within the polis. It’s either a political joke or a political omen. And Liz Cheney is at the center of that tension. Regardless of where you fall on the spectrum, her Oath and Honor—a look inside of what led up to that day, what happened on that day, and the events following that day from an eyewitness—should be read by every American who values the rule of law and loves our Constitutional republic.

The Flavor of Texas, J. Frank Dobie

Dobie is considered “the storyteller of the southwest.” More particularly, he’s the storyteller of Texas—and in The Flavor of Texas he does just that. The book is a smorgasbord of stories he read about or heard from old-time Texans, giving the reader a sampling or a taste of what it was like to live in such a wild and sometimes wicked place a century before Dobie’s book was published in 1936.

The Madstone, Elizabeth Crook

This novel is going to haunt me for a time. The sequel to her intriguing The Which Way Tree, Crook’s Benjamin Shreve, while doing a good deed, finds himself caught in a dangerous journey from Comfort, Texas, in the Hill Country, to Indianola, on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. Along the way, the orphaned nineteen-year-old creates an intimate bond with a pregnant teen (Nell) and her young son (Tot), who are fleeing from her husband and his murderous brothers. But because of a promise he made to his dying father in the previous novel, Benjamin cannot escape with them. In the end, he is left as alone as he was at the novel’s beginning.

Seuss-isms: A Guide to Life for Those Just Starting Out . . . and Those Already on Their Way, Dr. Seuss (Theodor Geisel)

In 1986, Robert Fulghum published All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten. It’s a common sense guide to life and the lessons learned as children: play fair, don’t hit people, put things back where you found them, clean up your mess, and flush the toilet. The folks at Random House have come up with their own common sense guide to life using the lessons taught by Dr. Seuss: surround yourself with good people, think before you speak, tell the truth, respect your elders, and others. Each lesson is taught in miniature from a quote from one of Dr. Seuss’s books, making this, for someone my age, a nostalgic walk through childhood.

Telling the Truth: The Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairy Tale, Frederick Buechner

This is the third or fourth Buechner book I’ve read. None of them long—100 pages or less—but each punches above its weight. He is that rare writer where virtually every sentence is pregnant with meaning. Telling the Truth doesn’t disappoint in that regard. Though I didn’t always agree with his theological conclusions or biblical exegesis, there is much in this slim volume to mull over when approaching the task of writing about or preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ.

What a World of Wonder! An Appreciation of J. Evetts Haley: Cowman, Historian, American, Evetts Haley Jr. (ed.)

J. Evetts Haley was one of the preeminent historians in Texas. His history of the XIT Ranch (1929) and his biography of Charles Goodnight (1936) have stood the text of time. To this day, they are considered the quintessential volumes on these two subjects. But these two of his are by no means the only books serious students of Texas history, particularly of the Texas west, should read. Haley was from a generation that believed history was made and moved by the actions of significant individuals, not impersonal forces of society or culture. He was honored by Hillsdale College with a Doctor of Letters in celebration of that philosophy and practice. What a World of Wonder! is a compilation of essays and speeches by his contemporaries on that achievement.

A Journey with Jonah: The Spirituality of Bewilderment, Paul Murray

Irish Dominican frier Paul’s Murray’s short contemplation on the book of Jonah is insightful and provocative. Some of his applications are practical, though he trends toward the mystical—St. Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross are favorites to quote. Nevertheless, this is a book worth thinking over.

Novelist as a Vocation, Haruki Murakami

Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami’s book on writing and the writing life is unique among writerly-type books. Most, in all or in part, follow the pattern of How To, including Ernest Hemingway’s On Writing, Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird, and Stephen King’s On Writing (the best of the bunch in my opinion). Murakami’s is different. You’ll find no admonishments about cutting adjective and adverbs, using active verbs or descriptive nouns. What you will find is a semi-biographical account of how one artist became a novelist and built a successful career. Some of his insights are adaptable for anyone desiring a career as a novelists, but much isn’t—not unless you’re Haruki Murakami.

Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, Salman Rushdie

On August 12, 2022, at the Chautauqua Institute in Chautauqua, New York, novelist Salman Rushdie walk out of the stage for an interview. Before he could sit in his chair or answer a single question a young man robed in black ran down the aisle brandishing a knife—a knife he plunged into the eye, cheek, hand, neck, and chest of Rushdie. Miraculously, Rushdie survived. Though an atheist (a fact he goes to pains to point out), he wrote about that miracle—a word he ironically uses to describe his survival—in a short memoir about his life just before the attack and his life since the attack, the account of which is horrendous. And the account of healing, physical therapy, and lingering terror for himself, his wife, and family is heartrending.

Steal Like an Artist: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being Creative, Austin Kleon

Well, this isn’t exactly true, not for me at least. Some of the things Kleon mentions in his interesting and well-designed book somebody already told me. But perhaps I’m not your average reader when it comes to creativity books, having read my fair share and taken courses in creativity. None of this, however, takes away from what Kleon has compiled here—and in the visually curious way he presents what he’s complied. It obviously resonates with readers. It’s a New York Times bestseller and the volume I read was the tenth anniversary edition. If you’re looking for a creative spark to spark your creativity, Steal Like an Artist just might be the spark you need.

Cricket: The Second-Chance Pirate, Kristi McElheney (illustrations, Matthew R. Reed)

This delightful children’s book is an allegory of the Christian life. It’s the story of a girl named Cricket, whose one goal in life is to become “the most swash-buckling, sword-fighting, eye-patch-wearing, pirate around.” She get’s her chance when “Captain” takes her aboard his ship and gives her a job to do: watch for whales and notify Captain when she spots them. When she does see the whales nothing comes out of her mouth. The ship would have crashed into them if it wasn’t for the quick action of Captain. Because she failed, Cricket believes she’ll never reach her goal—until Captain gives her a second chance. McElheney, a child development expert, ends her book with fun exercises for kids and thoughtful discussion questions for parents.

Texas, Being: A State of Poems, Jenny Browne (ed.)

Poetry isn’t my usual flavor but Texas is, and this interesting little collection of Texas related poems was a pleasure to dive into.

Larry McMurtry: A Life, Tracy Daugherty

Shortly after his death, the actress Cybill Shepherd called Larry McMurtry “one of the greatest men who ever lived.” McMurtry, if he had been around, would have laughed. He viewed himself as a “minor regional novelists.” In American letters, at least in the generation of whom he was apart, only Flannery O’Connor made his “major” list. Nevertheless, McMurtry did think “some kind of biography” might be written about his life. Tracy Daugherty has done just that, and has given us a intimate portrait of a complex writer who at times grew weary of his own words and with the world. McMurtry, like his cowboy relatives before him, had a wanderlust—a near aching need to see what was over the next horizon. But instead of rounding up cattle, he rounded up words and sentences. Over a long and distinguished career, McMurtry mastered three writerly professions: novelist/essayist, bookman, and screenwriter. Each those these professions is masterfully woven together in Daugherty’s highly readable biography. A must read for any McMurtry fan.

Oh What a Slaughter: Massacres in the American West, 1846–1890, Larry McMurtry

McMurtry is known as a novelist, having written thirty-one works of fiction. He was also an insightful and interesting essayist and amateur historian. Of all his writing, I believe his weakest works are his histories, not because he fails to find the facts nor because his writing is somehow less than what we’ve come to expect from McMurtry, but because his historical judgement is not as well informed as his novelistic judgement. A good example is his short book on American massacres in the mid-nineteenth century. More of an introduction to massacres within the United States, Oh What a Slaughter glosses over the motivations and hatred whites had for American Indian during these years, while at the same time giving a pass to native peoples and the atrocities they committed on one another. I suggest the book only as a pointer to works that deal with these issues in a more nuanced and complex manner.

Signals of Transcendence: Listening to the Promptings of Life, Os Guinness

Much of Os Guinness’s writing centers on the questions, “What is the purpose of life and what does that mean, practically, for every individual?” In his companion to The Great Quest: Invitation to an Examined Life and a Sure Path to Meaning, Signals of Transcendence speaks to the still small voice or the inner promptings that causes us to search for the answers of life. Though Guinness doesn’t quote him, Oswald Chambers provides a useful summary of the book’s theme: “The call of God is like the call of the sea, no one hears it but the one who has the nature of the sea in him.” Guinness would only add, if the one who has the nature of the sea in him has ears to hear—is attentive to and hasn’t drowned out the calling. Through a series of biographies, Guinness points out that each of us has a unique sensitivity, like the one who has the nature of the sea or the nature of the mountains within him. For some, the call or signal of transcendence—the splinter in our souls that says, “There’s more to this life than this life”—only comes through a sense of home or homelessness, love, joy, gratitude, or death.

The Iliad, Homer (trans. Emily Wilson)

Western Civilization was built on the backs and intellects of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Two foundational works that informed Greek culture were Homer’s twin epics: The Iliad and The Odyssey. Both center on the Trojan War. Virgil, the Roman poet, crafts the Romanesque version of The Odyssey in The Aeneid, following the adventures of Aeneas, leader of the few Trojan men who survived the war. The war itself is captured in The Iliad, wonderfully translated by Emily Wilson, whose language jumps off the page and brings the warriors to life—the Greeks Achilles, Agamemnon, the two Ajaxes, and Odysseus, as well as the Trojans Hector, Paris, and Priam. What is missing from The Iliad, which comes as a surprise to many, is the classical ending of the war—of the Trojan Horse (which we read about in The Aeneid) and the killing of Achilles, arrow shot in his heel from Paris’s bow and guided by the god Apollo (recorded in later myths). Though The Iliad is the least read and known of the two epics Homer penned, if you are interested in reading about the Trojan War then you must start here—and Wilson’s translation is one I recommend. Superb.

Greenlights, Matthew McConaughey

Full confession: I didn’t finish McConaughey’s memoir/biography/rumination—or however this incoherent mess is classified. I understand he has reached the status of public sage—through the careful marketing of his Lincoln and Pantalones Tequila commercials, and the silkiness of his Texas drawl. I didn’t have to get far into the book to realize that the sage has very little to say. His musings are koan-like, but are inchoate and on a desperate search for a philosophy. They never find sound footing and come off as pompous and cheap motivational rah-rah. But that wasn’t even the worst of it. It was painful to read the stories of his parents. He clearly loved them, but he had nothing good to say about them (at least in as far as I was willing to subject myself to reading about them). His father was nothing but a bully, who not only challenged his oldest son to a fist fight but threw the first punch. His mother had a bazaar set of morals, passing on the “virtue” of lying and stealing. During a seventh-grade poetry contest she told young Matthew to submit a poem by Ann Ashford, saying, “If you like it, and you understand it, and it means something to you, it’s yours . . . write that.” He did, passing it off as his own, and won the contest. Or, I say, Ann Ashford did. This is no way to rear a child. The fact that he survived his childhood and became a successful actor (ironic that) didn’t make him wise if this book is any indication. It just made him phony.

Under the Skin: Tattoos, Scalps, and the Contested Language of Bodies in Early America, Marin Odle

If the title sounds academic, it is. Professor Odle offers a dense study of tattooing and scalping among Native Americans in the Colonial and Revolutionary period of American history. Due to the nature of scalping in my own book, Blood Touching Blood, my interest was primarily focused on the chapters concerning scalping—the bounty on scalps, collected by both Indians and Anglo settlers, and the brutality of taking scalps from living victims. Delving into such a dehumanizing practice doesn’t make for easy reading, but the insights Professor Odle offers are valuable for understanding the motives for taking scalps and the psychological impact being scalped had on surviving victims.

Why Read Moby-Dick, Nathaniel Philbrick

In this short and punchy book historian Nathaniel Philbrick, the author of In the Heart of the Sea about the true story of the Essex that was struck and sunk by a sperm whale, lays out reasons why we should read Herman Melville’s classic Moby-Dick; or, The Whale. Philbrick places Melville and his novel within the historic context of what was happening in his personal life and within the life of the nation at the time of composition. Addressing some of the significant themes in Melville’s novel, Philbrick concludes, “This redemptive mixture of skepticism and hope, this genial stoicism in the face of a short, ridiculous, and irrational life, is why I read Moby-Dick.”

On Heroism: McCain, Milley, Mattis, and the Cowardice of Donald Trump, Jeffrey Goldberg

This short collection of articles from The Atlantic, written by Jeffrey Goldberg between 2018 and 2023, makes the case that Donald Trump, in comparison to Vietnam POW and United States Senator John McCain, Army General and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley, and Marine Corps General and Secretary of Defense James Mattis, is a man without courage, conviction (beyond his own self-interest), or honor. He is a man ignorant of American history, indifferent to military traditions, and insolent of constitutional order.

Cloudspotting for Beginners, Gavin Pretor-Pinney (illustrations, William Grill)

In this charming book, beautifully illustrated by William Grill, children and children-at-heart learn how to identify various clouds from a common cirrus or cumulus to the uncommon cavum or lacunosus. You’ll learn how a thunderhead and tornados form, as well as something about clouds on other planets.

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Ron Hansen

Like Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels, which won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in in 1975, Hansen’s The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford is a true historical novel. Recounting the story of the James Gang and the killing of Jesse by the erstwhile gang member Robert Ford, I can’t speak to the historical accuracy of the novel, but the language employed is timely and evocative. Not as lyrical as Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, Hansen’s style, nevertheless, is affecting, causing me to revisit sentences and paragraphs just to bask in the language. Until reading Hansen’s novel about Jessie James and Robert Ford only McCarthy and Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It has had such an affect on me.

In My Time of Dying: How I Came Face-to-Face with the Idea of an Afterlife, Sebastian Junger

Many of Junger’s books deal with death. A war correspondent, and producer of the acclaimed documentary Restrepo, about combat in Afghanistan, Junger has had his share of close calls. He knows firsthand what Winston Churchill meant when he said, “Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.” But it wasn’t until, in the safety of his Cape Cod home, an aneurysm in his pancreas ruptured that forced him to really contend with death and the possibility of an afterlife. A skeptic, Junger tells the story of his near death experience and wrestles with the physical and metaphysical questions about the hereafter.

Revealing Character: Texas Tintypes, Robb Kendrick

As Kynn Patterson says in Robb Kendrick’s wonderful collection of modern-day tintypes of working cowboys: “As long as cows still run on rough country, there will be cowboys.” A photographer with credits at Sports Illustrated, Smithsonian, and National Geographic, Kendrick, in the early part of the 2000s, traveled to some of the most storied (and unheard of) ranches in Texas to photograph working cowboys. Using a nineteenth-century technique, his tintypes of working men and women are beautiful and evocative.

All Things Left Wild, James Wade

James Wade is a Texas novelist. His debut novel, All Things Left Wild won the 2021 Spur Award for best western. And yet, I’m not sure what the judges saw in this book. I came to it with high hopes but struggled to connect with the story and the characters. As such, I didn’t finish it. I wanted to but couldn’t quite make it. I can’t put my finger on what the trouble was for me. It’s not the writing. He’s a good writer. I’ll come back to it at a later date and give it another shot. But until then, on to other books.

Texas Rivers, Taylor Bruce

Texas Rivers is a photo almanac and book of essays from the folks at Wildsam, the travel guide publisher. Not only do three icon rivers—the Red, Sabine, and Rio Grande—contribute to Texas’ icon shape, but its interior rivers are the lifeblood of the state. The editors at Wildsam, along with the contributing essayist and photojournalist, have tapped into that lifeblood and produced not only a beautiful book but a provocative one, as well.

Famous Stutterers: Twelve Inspiring People Who Achieved Great Things While Struggling with an Impediment, Gerald R. McDermott

I’m not a stutterer. But as a lover of the spoken (and written) word I’m interested in impediments that keep folks form articulating their thoughts. This short book by McDermott, who is a stutterer, isn’t a “how to” overcome the impediment of stuttering, but an encouragement to those who suffer. Like the men and women profiled in its pages, they too can learn to manage their impediment and success in life.

Dracula, Bram Stoker

Stroker’s classic horror novel, written as a series of journal entries by the principle characters, with the exception of Dracula, is great fun to read. Better yet when you read it with a loved one. A wonderful way to do that is to sign up for the newsletter, “Dracula Daily,” which sends out an email with readings corresponding to the journal entries, beginning on May 3 and ending on November 7.

Books are Made Out of Books: A Guide to Cormac McCarthy’s Literary Influences, Michael Lynn Crews

As the subtitle says, Crews’s book is a reference guide to those writers and their books that shaped Cormac McCarthy’s thinking and style. Titled from McCarthy’s famous dictum: “Books are made out of books,” this work is a must have for students of McCarthy.

Jesus and the Powers: Christian Political Witness in an Age of Totalitarian Terror and Dysfunctional Democracies, N. T. Wright & Michael F. Bird

This dense little book packs an intellectual punch, wrestling with practical Christian political involvement in the context of the coming kingdom of Christ. As citizens of Christ’s kingdom, Christians should not conform to any of the political ideologies that are all the rage these days, but should confront kingdoms that would draw our alliance away from Christ and His kingdom. In this way, we actually become better citizens of the countries in which we inhabit.

Last Stands: Why Men Fight When All is Lost, Michael Walsh

Walsh is a fine writer, yet at times, for my tastes, he tends to overwrite. One notable example is his propensity to favor the language of the academy over the language of the marketplace. That notwithstanding, Last Stands is an intriguing work—a look at some of the most famous last stands in history (the battle of Thermopylae, the Alamo, and Custer at the Little Big Horn), as well as a good number of the lesser known last stands (the Romans at Teutoburg Forest, the Jews at Masada, and the British at Rorke’s Drift). In tracing the history of these battles, Walsh inclines to place them within a religious context, pitting Christianity (particularly Catholic Christianity) against either native religions or Islam. In some cases, this is warranted. But in others, I believe he spreads too much butter over too little bread. (As an aside, his critique of the Reformation, Martin Luther specifically, is wrongheaded.)

Armadillo Rodeo, Jan Brett

A delightful children’s book about Bo, a wayward armadillo who, because he has poor eyesight, befriends a pair of red boots he mistakes as an unusual colored fellow armadillo. He and the red boot go on an exciting adventure to the rodeo.

Lonesome Dove, Larry McMurtry

It’s the quintessential Texas novel, y’all. What more can I say? Those who know, know. Those who don’t, should.

Blood Touching Blood, Derrick G. Jeter

A rather good debut novel, if I do say so myself. Blood Touching Blood probes the mystery of how violence begets violence, how the lust for vengeance hollows out the human soul, and whether one who gives himself to such dark designs can find redemption. Get your copy and tell me what you think about it.

If y’all’d like to support the work of Y’allogy saddle up and ride for the brand by becoming a paid subscriber or purchasing my book. Much obliged, y’all.

'Steal Like an Artist' was one of a very few watershed books on creative craft for me—it wasn't so much that it taught me something new as it was an "aha" moment of recognizing and embracing things done by instinct.

The tintype book sounds fascinating. And I know I have to read some J. Frank Dobie at some point—so far I've only crossed paths with him via quotations or as the author of forewords to others' books.