A Texan Abroad: The Jewel of the Renaissance and the Eternal City

I found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble.

Caesar Augustus

A Note to Readers: What follows is the third in a three-part series on my recent trip to Europe—a delayed celebration of thirty-five years of marriage. The first was “Jolly Ole England” and the second was “The City of Lights and the Beaches of Death.” As I’ve said before, for some, these “A Texan Abroad” articles may come across as enduring my vacation slides. If that’s you, feel free to excuse yourself, new Texcentric content is over the horizon. For others, this miniseries might give you ideas for your own future travel plans. Whether you travel near or far, vaya con Dios.

All leads to Rome. Or so they say. Ours did, but not before it passed through one of the most beautiful cities in Europe: Florence—the Jewel of the Renaissance. Here, under the power and patronage of the Medici family, Renaissance art flourished, as is fitting with the city’s name—from the Latin florentius, meaning “to flourish.” Florence is a living museum, not only because of the Renaissance art on public display, but because the piazzas, streets, and buildings themselves produce a visual feast as you move through the city.

Florence is divided by the Arno River, originating in the Apennines Mountains. The historic and cultural center is located on the northern bank. Because the city is delightful to behold, it’s worth the time and effort to cross one of the many bridges over the Arno to the southern side and climb Piazzale Michelangelo. That lush and watered hilltop offers the best views of the city and its many famous buildings—the Loggia dei Lanzi, Palazzo Vecchio, Uffizi Gallery, Ponte Vecchio, Basilica di Santa Croce di Firenze, Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore, and Battistero di San Giovanni.

We arrived in Florence on the twelfth day of our trip. We arrived in the rain. Our plane did not taxi to the terminal, but parked on the tarmac, forcing us to disembark down the back stairs and dash to a waiting tram to take us to the terminal. After retrieving our bags, we found our driver and made our way through the narrow streets to the heart of the city and the center of the fashion district to the hotel Isabella, nestled in the middle of a Gucci store.

After a glass of wine in the hotel lobby, we retired to our room to rest, shower, and change for dinner. The evening was rain free. The air was clean and crisp. We found a little bistro along the river and sat in the back, near the open kitchen where we could watch the chef prepare our meal. After dinner, we walked the river and through Piazza di Santa Trinita, up Via de Tornabuoni, leading to our hotel, past Tiffany & Co., Burberry and Fendi, Prada and Yves Saint Laurent, and Armani until we arrived at our Gucci hugged room.

Day thirteen caught us early. After breakfast, we strolled the short distance from our hotel to Piazza della Republica where we met our guide for a walking tour of the city. We saw the famed Ponte Vecchio where fishmongers used to sell their catches until the Medicis, who crossed this bridge daily grew tired of the smell of fish, bought the fishmongers out and replaced their bridge-lined shops with gold and silversmiths. We walked along the arched Lungarno deli Archibusieri, on the northern bank of the Arno, to the Piazzale deli Uffizi, where statuary of Leonardo da Vinci, Dante Alighieri, Nicoló Machiavelli, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Galileo Galilei, and others—twenty-eight in all—stare down on you as you make your way to Piazza della Signoria. There, in front of the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence’s town hall, stands a copy of Michelangelo’s David—located in the same spot where the original David stood for centuries before being moved to the Galleria dell Accademia. Adjacent to Palazzo Vecchio is the arched portico of the Loggia dei Lanzi (Loggia della Signoria) where Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus with the Head of Medusa and Giambologna’s Hercules and Nessus and his Rape of the Sabine Women (and other statuary) stand in testament to the creative beauty of the Renaissance.

From there we wove our way though the slender streets until we came to Piazza del Duomo, dominated by the imposing and magnificent Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore (Duomo), Battistero di San Giovanni (Baptistry of Saint John), and Giotto’s Campanile (tower). Before moving on to the Accademia we marveled at the cathedral, constructed in tricolored marble of white, red, and green. Atop is a red-roofed dome. And the octagonal baptistry, constructed out of the same three-colored marble, is accessible on each side by massive and finely detailed double doors cast in bronze. Each door panel depict biblical stories, from Adam and Eve to Pentecost, the four gospel writers and early church fathers, as well as eight Christian virtues.

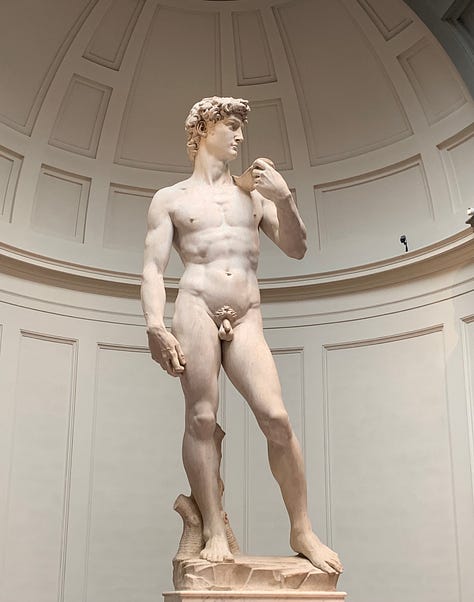

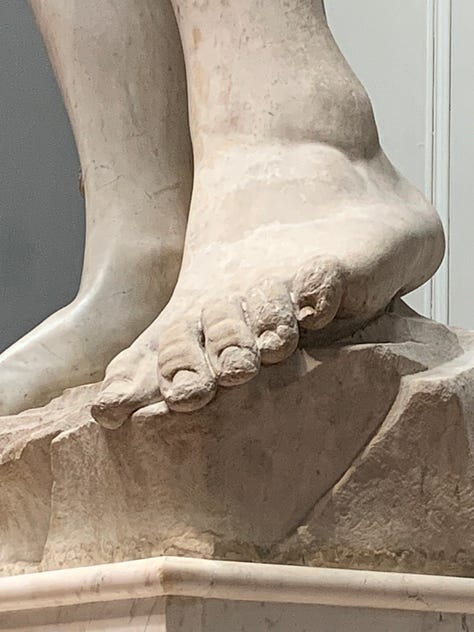

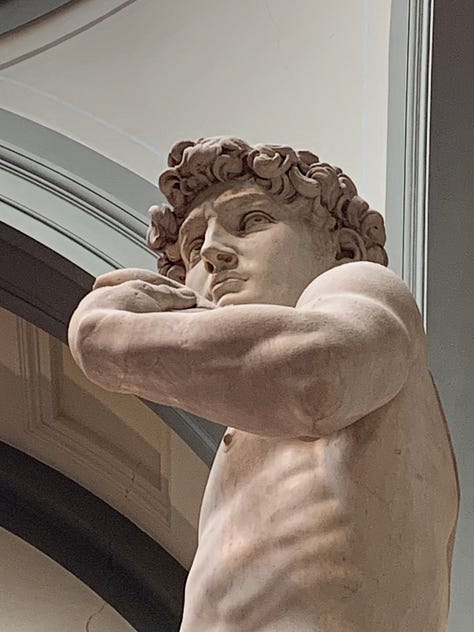

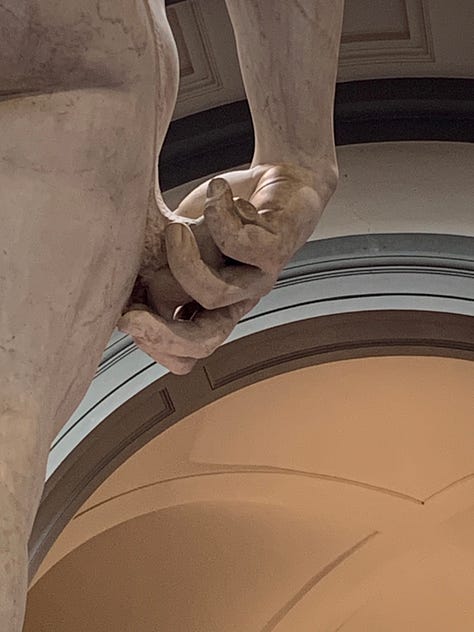

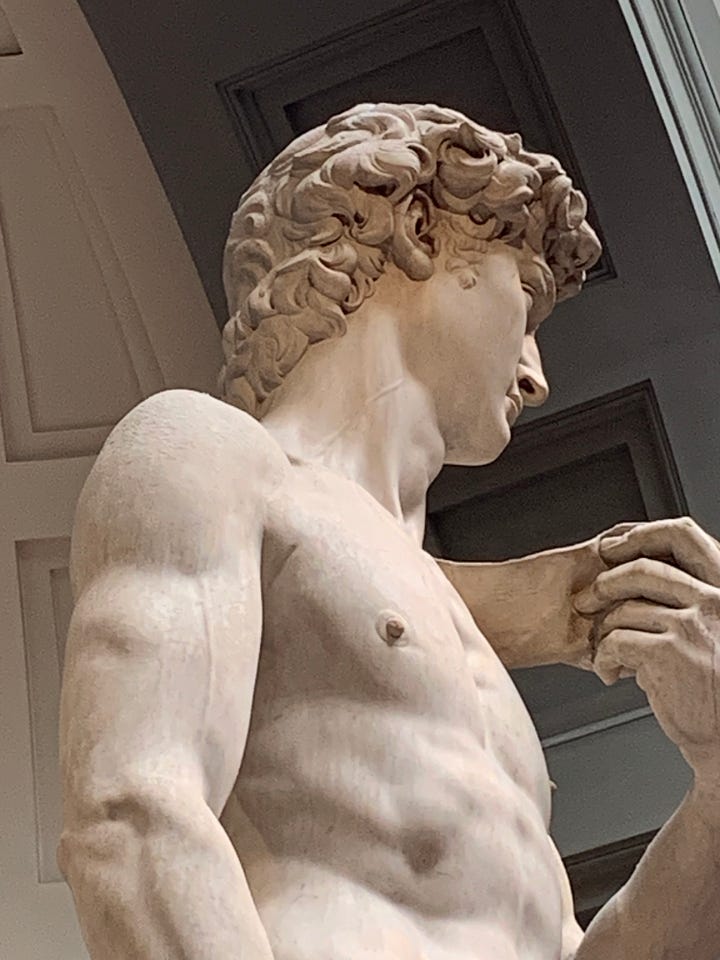

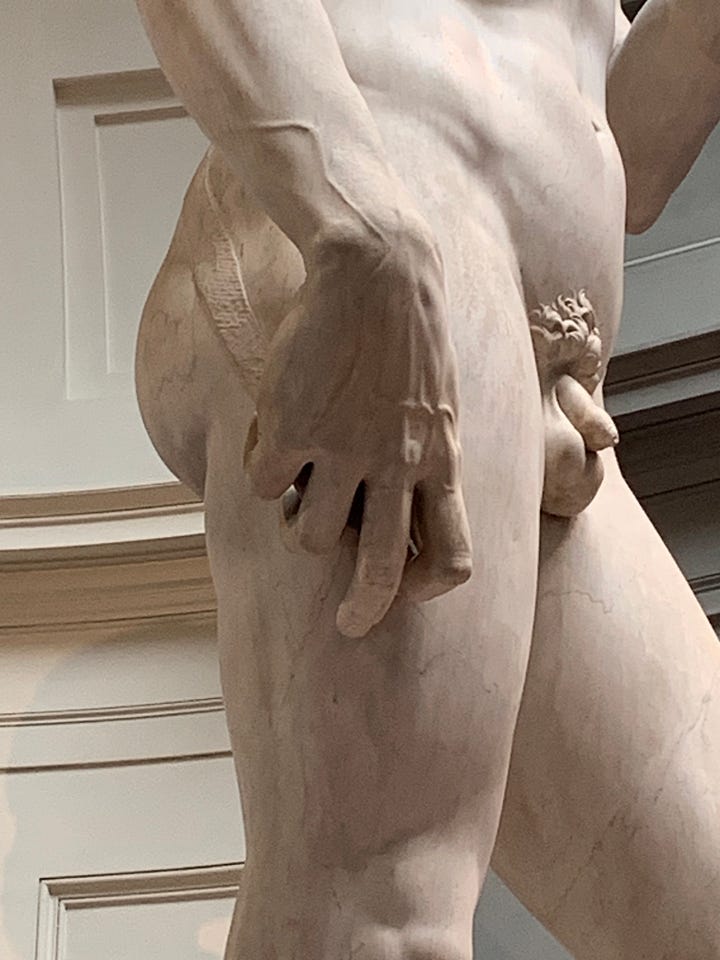

Making our way through the crowd we arrived at the Accademia to view Michelangelo’s masterpiece: the seventeen foot tall David. It is carved from a single piece of marble—and from reports by experts, a poor piece of marble at that. Michelangelo began working on the David in 1501, when he was twenty-six years old. He finished three years later, in 1504. The atomically correct details—the muscles in the arms, legs, and trunk, the veins in the hands, the nails and digits of the toes (even the ones hammered by a vandal in 1991)—are astounding. The David is the most magnificent object of human creation I have ever seen. It is simply sublime.

The Accademia boasts other celebrated works, including the plaster mold of Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabine Women, Michelangelo’s four unfinished Prisoners, as they are called, which were intended to grace the tomb of Pope Julius II, his unfinished Matthew, as well as the only fully original Stradivarius in the world—a viola built for the Medici family.

After the Accademia we lunched at an outdoor cafe and had our first taste of authentic Italian pizza. Gelato followed for dessert. Then it was on to the famous Uffizi Gallery, to walk among the treasures collected and commissioned by the Medici: Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo, da Vinci’s The Annunciation and Adoration of the Magi, Raphael’s Madonna of the Goldfinch, Caravaggio’s Medusa, and Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus. The morning and afternoon had been sunny and warm, but by the time we left the Uffizi a steady rain was falling—and showed no signs of ceasing. Making our way back would be a wet one. And it was. Thankfully, by dinnertime the rain stopped, the clouds were parting, and the stars were shining. And the beauty of the street lit city shimmered in the watered cobblestones.

Day fourteen was a busy one. After breakfast in the hotel, we crossed the Arno and climbed the hill of the Piazzale Michelangelo to take in the commanding charm of the city below. Then back down the hill and across the Arno to the Basilica di Santa Croce to visit the tombs of Michelangelo, Galileo, and Nicoló Machiavelli. For lunch, we found a nice outdoor restaurant and ordered spaghetti, thick and chewy, and lasagna that came boiling in a rich and creamy sauce. The rest of the day was spent wandering the streets, eating gelato, and shopping for leather goods.

That evening, after dinner, we walked along the river and stood on the Ponte Santa Trinita (bridge) and watched the sinking sun sizzle into the western waters of the Arno.

Day fifteen found us on another train. This time to Rome. When we arrived we decided to stretch our legs and walk the short distance from the station to our blue-fronted accommodations, the iQ Hotel Roma, across the street from the Rome Opera House. After checking in, unpacking, and resting a bit we made our way through the crowded and noisy streets to the Colosseum (the Flavian Amphitheater), built between AD 72 and 80, under emperors Vespasian and Domitian. Before our tour, we had lunch in the shadow of that famous façade. After lunch, however, we stood in the sweltering heat in the midst of a crushing crowd waiting to enter the Colosseum. This would prove to become a precursor of the remainder of our trip. The outside temperature was torrid, the surrounding crowds were suffocating, and, I confess to my shame, my inner temperature was fevered. I’m a Texas boy who loves the spaciousness of wide spaces and hates to be herded.

The Colosseum itself was a wonder of human ingenuity and engineering. Depending on how things were configured, anywhere between 50,000 and 80,000 people could find a seat for a day’s entertainment. But the Colosseum was also a testament to human cruelty—of what man will do to his fellow man because of hubris and hatred. It was built by more than 100,000 slaves, captured by Rome’s armies, most of whom were Jews, deported to Rome after the destruction of of Jerusalem in AD 70. When Domitian opened the inaugural games, which lasted one hundred days, upwards of two thousand gladiators lost their lives. In over three and half centuries of violent sports and spectacles the blood of at least 400,000 people muddied the Colosseum’s dirt—to the cheers of the crowds. Animals that died in the Colosseum numbered in the untold millions.

A short distance from the Colosseum, along the temple lined avenue of the Via Sacra—the “Sacred Street”—past the Tempio di Venere (the Temple of Venus) and the Arch of Constantine, through the Arch of Titus, built in celebration of his conquest of Jerusalem on AD 70, is the Roman Forum (Forum Romanum), the ancient political, legal, and religious center of the Eternal City, as well as the Palatine Hill (Palatino), one of the famous seven hills of Rome (the others being Aventine, Caelian, Capitoline, Esquiline, Quirinal, and Viminal). The Forum is filled with the ruins of this once great empire. Climbing the Palatine, where according to legend Romulus founded Rome in 753 BC, and where the ruins of a residential neighborhood stands—home to renowned Romans like Cicero, Crassus, Augustus, and Tiberius—you have a commanding view of the entire Forum and what was once a city of power and beauty.

At the bottom of the hill, our guide ended the tour next to one of those ruins—the temple housing the tomb of Julius Caesar.

Day sixteen found us outside the Vatican. Our travel agent couldn’t arrange an audience with Pope Francis, but along with 10,000 of our closest friends, we could be herded through the Vatican Museum, the Sistine Chapel (where no photos were allowed and we were allotted ten to fifteen minutes, standing like sardines in a can, to marvel at Michelangelo’s remarkable ceiling fresco), and St. Peter’s Basilica (where photos were allowed and we could take our time). Once we explored the Basilica, we took the stairs down into the crypt to see the supposed tomb of the apostle Peter. Something tells me the simple fisherman from Capernaum in Galilee would not be pleased with the ornate, golden shrine that sits under the alter of the Basilica.

After our visit at the Vatican we grabbed lunch and then made our way back to the Forum. I had long wanted to see Carcer Tullianum Museo—the Museum of the Tullius Prison, better known as the Mamertine Prison. It’s a subterranean structure consisting of two vaulted chambers, one above the other and connected by a small hole. Tradition dates the construction sometime between 640–614 BC, when it was originally built as a cistern. In time, however, it was converted into a prison. For the most part, prisoners occupied the upper level. But when it came time for their execution, they were lowered through the opening into the oubliette or dungeon. Today, a spiraling staircase takes you to the bottom. According to tradition, Peter was imprisoned there, performing baptisms with water at the bottom of the pit before being crucified upside down.

Peter probably was imprisoned in the Mamertine before his death in about AD 67. But there’s little doubt the apostle Paul was imprisoned there from the spring of AD 65 until sometime in AD 68, when he, as a Roman citizen, was beheaded. It was from here Paul penned some of the most stirring words found in the Bible. To his young protégé Timothy, Paul wrote,

Make every effort to come to me soon; for Demas, having loved this present world, has deserted me and gone to Thessalonica; Crescens has gone to Galatia, Titus to Dalmatia. Only Luke is with me. Pick up Mark and bring him with you, for he is useful to me for service. . . .

When you come bring the cloak which I left at Troas with Carpus, and the books, especially the parchments. . . .

At my first defense no one supported me, but all deserted me; may it not be counted against them. But the Lord stood with me and strengthened me, so the through me the proclamation might be fully accomplished, and that all the Gentiles might hear; and I was rescued out of the lion’s mouth. The Lord will rescue me from every evil deed, and will bring me safely to His heavenly kingdom; to Him be the glory forever and ever. Amen. . . .

Make every effort to come before winter. (2 Timothy 4:9–11, 13, 16–18, 21)

“Come before winter.” Those were the words that stabbed at my soul as I made my way down the stairs into the darkness of that dingy dungeon. Standing there, in that blackened cistern, I tried to imagine a bruised and abused man, dressed in dirty summer linen as spring’s warmth faded in the face of winter’s chill, stooped over a little wooden desk with a single clay lamp scribbling his final letter to his friend and spiritual child, Timothy. The words haunted me: “Make ever effort to come before winter.” For twenty minutes or so we stood in that prison cell in silence. It was sacred.

That evening we had dinner with Dallas friends, who were on a separate tour, Jim and Amber Craft.

Day seventeen was a long, hot one. It began early in the morning with a three hour bus drive from Rome to the Amalfi Coast and Pompeii. About halfway there we stopped at a tourist trap cafe for donuts and water. Another hour later we arrived at Positano, one of the beautiful cliffside towns along the Tyrrhenian Sea. Unfortunately, we only had an hour and half to explore the crowded hillside village before loading the bus and heading to Pompeii, the ancient city sitting in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius. Like Positano, we only had an hour and half or so to explore the ruins of this once thriving Roman town. We saw the plaster casts of the people who died where they fell as volcanic gasses and ash filled the sky, chocking the air, and burning their lungs. We walked the streets and passed the shops where day-to-day of life took place. We explored homes with beautiful painted murals preserved by Vesuvius’s pumice and ash. We visited the marketplace and the temples of Jupiter and Apollo, where crowds used to gather.

None but tourists, creatures of the ground, and birds of the air inhabit these streets and homes today. The destruction of Pompeii in AD 79 was a tragedy for those who lived there. The decay of this archeological wonder is a tragedy for all who care about the preservation of history. Footpaths and roadways are worn down by the nearly 3 million tourists who visit each year. Exposed to the elements, invasive plants infest streets and buildings, and in 2010 the Schola Armatorum—“House of the Gladiators”—collapsed due to heavy rains and a lack of proper drainage. Arguments rage among various groups as to whether scarce resources should be used to preserve what has already been uncovered or whether more money ought to be spent on excavating other sections of the city. The debate continues.

The day ended with pizza, the bus ride back to Rome—and another stop at the tourist trap cafe.

Day eighteen, and the last full day of our European trip, was spent in Rome, eating more gelato and checking off more of the must-see sites: the Pantheon and its famous oculus (hole) in the center of the coffered concrete dome (it also houses the tomb of the Renaissance painter Raphael), Trevi Fountain, Piazza Novona, where we had lunch, and the Circus Maximum—the ancient Roman chariot-racing stadium.

Days nineteen and twenty were travel days. After changing gates three times at the Rome airport, we finally boarded our plane bound for Dallas and home.

In The Innocence Abroad Mark Twain wrote, “From the dome of St. Peter’s one can see every notable object in Rome, from the castle of St. Angelo to the Coliseum. . . . He can see a panorama that is varied, extensive, beautiful to the eye, and more illustrious in history than any other in Europe.”

We weren’t allowed to climb the dome of the Basilica, but the beauty of Rome from the heights is belied by the graffiti- and trash-filled streets when viewed from ground level. In this, we were disappointed that the eternal city should have taken on such a temporal and degrading façade. In comparisons to Paris and Florence, in particular, Rome may yet command a more illustrious history than any other in Europe, but cannot command the charm and beauty of those other European cities.

And yet, Rome remains beautiful. Like a dirty-face child. For me, Rome was a pilgrimage: to stand among the ruins of that once mighty empire—an empire that ruled the world in which my Lord and Savior lived and died, crucified as a criminal and rebel to Roman rule—and to stand where Paul stood, sentenced to die for preaching salvation through the crucified and risen Christ. And in that way, Rome remains beautiful to me.

Thank you, Misty. You've expressed exactly what I hoped to accomplish with these tour articles, to you an idea of what it's like to be there and to help you plan your own European vacation.

Great read, thanks Derrick I feel like I've been on a little tour of Italy now! 👍