A Texan Abroad: The City of Lights and the Beaches of Death

What an immense impression Paris made upon me. It is the most extraordinary place in the world!

Charles Dickens

A Note to Readers: What follows is the second in a three-part series on my recent trip to Europe—a delayed celebration of thirty-five years of marriage. The first article was “Jolly Ole England.” As I said then, for some, these “A Texan Abroad” articles may come across as enduring my vacation slides. If that’s you, feel free to excuse yourself, new Texcentric content is over the horizon. For others, this miniseries might give you ideas for your own future travel plans. Whether you travel near or far, vaya con Dios.

Ah, Paris. City of lights. City of lovers. You beguiled this Texan whose ancestors fled persecution in France and settled in the area of another Paris—Paris, Texas. Unlike London whose complexion is eclectic, with her gleaming skyscrapers stand beside buildings that might be described as démodé, there is a uniformity to your complexion—a beauty and balance wherever the eye settles.

Such was my introduction to Paris when we stepped off the train from London on the seventh day of our European journey.

Navigating London’s Underground proved a simple task. The Paris subway not so much, if for no other reason than I’m fairly adept in the English language but proved fairly inept in the French language. But we managed to find our way to a stop near our accommodations, along the Tuileries Garden. Our hotel, Le Relain Saint-Honoré, a more modern affair than Batty Langley’s in London, is situated a block or two from the Louvre. After checking in and riding the elevator that might have been used as a dumbwaiter in a previous life, we strolled through the old palace courtyard of the Louvre, across the Tuileries Garden, over the Pont Royal Bridge and the River Seine, where Javert in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables drowned himself. We were greeted at the Musée d’Orsay by a replica of the Statute of Liberty—Vive l’Amérique—where we explored the Impressionist, including an exhibition of Manet and Daga.

That evening we dined at an open air cafe and enjoyed the (borrowed) life of a Parisian.

Day eight of our twenty day European adventure kept us in the comfortable confines of the city. We had a private walking tour. Our guide, an Irishman, took us first to the burned out shell of Notre-Dame. We stood on the street watching construction workers ant over scaffolding in their labors to revive the nearly seven-hundred year old Lady of Paris after the 2019 fire nearly consumed her. The roof had been replaced over the centuries old skeleton, but the interior remained a hallowed shell.

Turning our backs on the the scared beauty of Notre-Dame, we made our way through the famed Latin Quarter and stumbled upon the equally famed Shakespeare & Company (at 37 rue de la Bûcherie), the bookstore where expat Anglophone writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, and T.S. Eliot met, drank wine, and discussed literature and politics. I was disappointed to learn, however, this isn’t the original Shakespeare & Company which was opened by Sylvia Beach in 1919 (at 12 rue de l’Odén), who originally published Joyces’s Ulysses. The current bookshop was opened in 1951 by George Whitman in a seventeenth-century monastery, La Masion du Mustier, on the opposite bank of the Seine from Notre-Dame. The original name of the store was Le Mistral. But in honor of Ms. Beach, who died in 1962, Whitman adopted the name of her original shop.

From Shakespeare & Company we passed the observatory at the University of Paris (the Sorbonne), one of the city’s oldest churches, the Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre, which boasts a strange theological amalgamation of Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic, as well as jazz clubs that roared during the roaring twenties. After a brief stop at the Palace Dauphine, we made our goodbyes to our guide at the Statue Équestre d’Henri IV near the northern tip of Île de la Cité, one of the islands in the middle of the Seine.

After a quick lunch, we hopped a tour bus and drove north on Quai d’Orsay to Pont de la Concorde, crossed the Seine, and then around Place de la Concorde (the Egyptian obelisk). From there, we made our way down the most famous street in the world: the Champs Elysées on our way to the L’arc de Triomphe de l’Etolie, where a perpetual flame burns at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. We spent a good deal of time there. With the Paris traffic circling us, I remembered the more than one million Frenchmen who lost their lives in World War I, including the unknown soldier laid to rest under the arch, and the images of jackbooted Nazis goose-stepping through the arch after the fall of Paris in World War II.

Back on the tour bus, we drove back down the Champs Elysées away from the Arc de Triomphe. We turned on Avenue George V and drove past the Flame of Liberty, which marks the entrance of the Pont de l’Alma tunnel where Princess Diana died in a car crash in 1997 while attempting to escape the paparazzi. We crossed back over the Seine and then down Rue de l’Université to the Eiffel Tower. After a bit of time marveling at that engineering achievement the day was waning—and so were we. We took the tour bus to the Musée d’Orsay where we got off for the short walk back to our hotel, where we showered and changed for dinner.

Day nine came early, with a train ride from Paris to Versailles. I thought I had seen the splendor of the kings and queens of Europe when I wandered the halls of Windsor Castle. But the poor kings and queens of England were living in the servants quarters compared to the opulence that is Versailles. The gilded gates, doors, and hallways gleamed with a grandeur as to be an obscene spectacle. The gardens are breathtaking. Strolling among such elegance I remembered something John Adams wrote after first seeing the Queen of France, Marie Antoinette.

She was an object too sublime and beautiful for my dull pen to describe. . . . Her dress was everything art and wealth could make it. One of the maids of honor told me she had diamonds upon her person to the value of eighteen million livres, and I always thought her majesty much beholden to her dress. . . . She had a fine complexion indicating her perfect health, and was a handsome woman in face and figure.

Adams wrote that in 1778. Tragically, fifteen short years later, in 1793, the beautiful Marie Antoinette lost her diamonds—and her head.

Back in Paris, our last evening in the City of Lights, we dined at what became our favorite cafe: Café Carrousel on Rue de Rivoli, across the street from Tuileries Garden. After a course of escargot, we walked through the garden and the courtyard of the Louvre, watching the lights of the Eiffel Tower glow and the lights of Paris shimmer on the Seine.

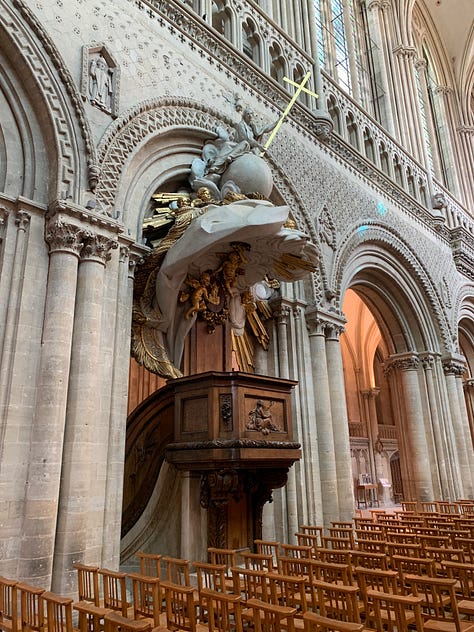

Day ten found us on another train. This time from Paris to the Normandy town of Bayeux, where we were booked into a charming bed and breakfast: Le Castel. Our room overlooked the village and La Cathédrale de Bayeux (Cathedral of Our Lady of Bayeux) with its soaring spires. The cathedral was consecrated on July 14, 1077, in the presence of William the Conquerer, the Duke of Normandy, who sailed the English Channel ten years earlier to claim the crown of Britain. His victory at the battle of Hastings in 1066 is celebrated in the Bayeux Tapestry. Because of the tightness of our schedule, however, we failed to see it.

A stroll through the village and dinner at a bistro just around the corner of the cathedral ended the day.

Day eleven was a sombre but proud one. We visited the American sites involved in the Allied invasion of France on June 6, 1944: D-Day. We began the day with a visit to La Cambe. Interred in this treelined plot of Normandy farmland, under crosses made of volcanic rock, are 21,222 German soldiers.

Though I abhor what they fought for, whether knowingly or unknowingly, there is no reason not to be magnanimous in honoring the bravery and sacrifice of these German dead, not if the French, who lived under their tyranny, provided this ground and buried these men with dignity. Winding my way through the graves I remembered something Darrell “Shifty” Powers of Company E of the 101st Airborne Division, who parachuted into Normandy on D-Day, said of the average German soldier, many of whom lay in the graves of La Cambe: “Under different circumstances we might have been good friends.”

From La Cambe we drove to Utah Beach. We arrived at low tide and but for a handful of visitors and harness racers exercising their horses all was quiet. We roamed the beach and imagined the armada afloat in the English Channel and the young men emerging from Higgins boats and crossing the same sanded ground where we stood, running into a hellstorm of machine-gun fire and mortars coming from the dunes behind us. Such bravery as the world has little seen was on public display that day by American soldiers no older than boys, who for the sake of liberating an oppressed people and for the survival of civilization stormed the French coastline.

Behind the beach is a bar and brasserie called, “Le Roosevelt,” named in honor of Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr., the oldest man and highest ranking officer to land in Normandy in the first wave. La Roosevelt is filled with World War II memorabilia: flags, unit patches, supplies of various kinds, radios, and uniforms. The walls are decorated with posters of TR Jr. and photographs, old and new, of the men who set France free. Along the walls, in between the photos, and along the bar and on the tables are messages and signatures of old men who were once young men in the summer of ’44.

Leaving Utah Beach we meandered through the French countryside, past the infamous hedgerows that proved formidable obstacles to men and material moving inland. Breaking out of the hedgerows into the lowlands that had been flooded some eighty years before by the Germans there emerged the village of Sainte-Mère-Église and its well known chapel. During the early hours of D-Day mixed units of the U.S. 82nd Airborne and U.S. 101st Airborne descended on the town. While many of his compatriots descended in the center of town and into flame-engulfed buildings, or in the main square where they were captured or killed, or got hung up in the trees and utility poles where they shot, Private John Steele’s parachute caught the church’s steeple, where he remained suspended, entangled in his line. For two hours he feigned death, until German soldiers captured him. He was portrayed by Red Buttons in the 1962 blockbuster The Longest Day. In commemoration of Steele and all the Americans who liberated Sainte-Mère-Église a dummy paratrooper hangs from one of the pinnacles of the church.

After lunch in a walled garden and a visit to the Airborne Museum, we left Sainte-Mère-Église for the bomb cratered cliffs of Point du Hoc, a promontory jutting into the English Channel. The Germans had fortified the highest with bunkers and captured French 155mm guns, which were capable of raining death on the men crossing the already deadly beaches of Utah and Omaha. Its destruction was vital. The job of sweeping the Germans from Pointe du Hoc fell to a Texan, Lieutenant Colonel James Earl Rudder, and his Ranger battalions. The attack began at sea level, at the bottom of the cliffs. With ladders and grappling hooked ropes, Rudder’s Rangers slowly scaled the cliffs. Their casualties were staggering. After two days of fighting, the initial Ranger force of 180 men was reduced to ninety capable of continuing the fight.*

Standing on the edge of Pointe du Hoc we were stuck by the awe-filling beauty of the English Channel and the awful ugliness of the remnants of war. The concrete bunkers, pillboxes, and observation posts are scars on the lush green plateau. Bomb craters dot the site all about. Now grass covered, they serve as a reminder of the capacity of human ingenuity to rain destruction upon mankind and upon the good earth.

There among the beauty and ugliness stands a granite monument honoring the granite courage of the Rangers who climbed those cliffs—“the boys of Pointe du Hoc,” President Ronald Reagan called them on the fortieth anniversary of D-Day. Standing in front of that dagger like memorial, surrounded by survivors of that hellacious climb, Reagan said,

We stand on a lonely, windswept point on the northern shore of France. The air is soft, but forty years ago at this moment, the air was dense with smoke and the cries of men, and the air was filled with the crack of rifle fire and the roar of cannon. At dawn, on the morning of the sixth of June 1944, 225 Rangers jumped off the British landing craft and ran to the bottom of these cliffs. Their mission was one of the most difficult and daring of the invasion: to climb these sheer and desolate cliffs and take out the enemy guns. The Allies had been told that some of the mightiest of these guns were here and they would be trained on the beaches to stop the Allied advance.

The day could have ended at Pointe du Hoc, such was my pride in being an American and such was my sorrow for the incalculable cost to American lives to secure liberty for an enslaved people. But we had two more sites to visit before the day was complete: Omaha Beach and the American cemetery.

Unlike Utah Beach, Omaha Beach was crowded with people. Like us, some were touring the battle sites. Others were boating, sunbathing, and swimming—enjoying themselves on a bright beautiful day in June. They could have been at Galveston or Padre Island. I asked our guide if there was a section of beach cordoned off for contemplation. He said, “No. The old veterans who have returned on D-Day anniversaries had been asked whether they would like the beach to be turned into a memorial. They said, ‘Let people enjoy the beach as they would any other beach. That’s what we fought for.’” Who am I to disagree?

There are markers and memorials on the seawall, as well as a section of a mulberry—a floating pontoon used to construct a temporary dock so deepwater ships could unload reinforcements, ammunition, food, and equipment needed to push inland. Just down the beach, hidden behind the dunes and among the trees is the first cemetery to bury the D-Day dead. Further down the beach is the permanent American cemetery: Cimetière Américain de Colleville-sur-Mer, where 9,387 men are buried—known and unknown. We arrived in time to stand guard over the flag lowering ceremony. We moved among our hero dead and paid our respects to Theodore Roosevelt Jr. and his little brother Quinten, who, in 1918, as a World War I flyer was shot down over France by a German ace. The Germans buried Quinten with honors at the village of Chamery, where he rested for the next thirty-seven years, until 1955 when his body was exhumed and placed next to his brother’s in Normandy.

We left the dead behind, lying in repose next to the beautiful beaches of Northern France and the clear, blue waters of the English Channel, grateful and humble. That evening, we dined quietly at an outdoor cafe in the shadow of the great cathedral that stands in the heart of Bayeux.

Day twelve was a day of travel. We took the train from Bayeux back to Paris, and then from Paris we caught a plane to Florence, Italy.

Having now been back home in Texas for the better part of two months since we walked the streets of Paris and the beaches of Normandy, two thoughts fill my mind. One is from Jacqueline Kennedy’s younger sister, Lee Radziwill, who said of the City of Lights and it beauty: “Paris is the most beautiful city in the world. It brings tears to your eyes.” A tear never came to my eyes in Paris, but I believe she may be right about its beauty.

The other thought is from Ronald Reagan who said of Normandy and the deaths that took place there: “We’re here to mark that day in history when the Allied armies joined in battle to reclaim this continent to liberty. For four long years, much of Europe had been under a terrible shadow. Free nations had fallen, Jews cried out in the camps, millions cried out for liberation. Europe was enslaved, and the world prayed for its rescue. Here in Normandy the rescue began. Here the Allies stood and fought against tyranny in a giant undertaking unparalleled in human history.”

* The original fighting force should have numbered 225, but LCA-860 sunk with thirty-five men aboard, and LCA-914 was disabled, leaving roughly 180 men to rush the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc. Peggy Noonan, who wrote President Reagan’s Pointe du Hoc speech, incorrectly referred to the wrong number.