A Plough Horse

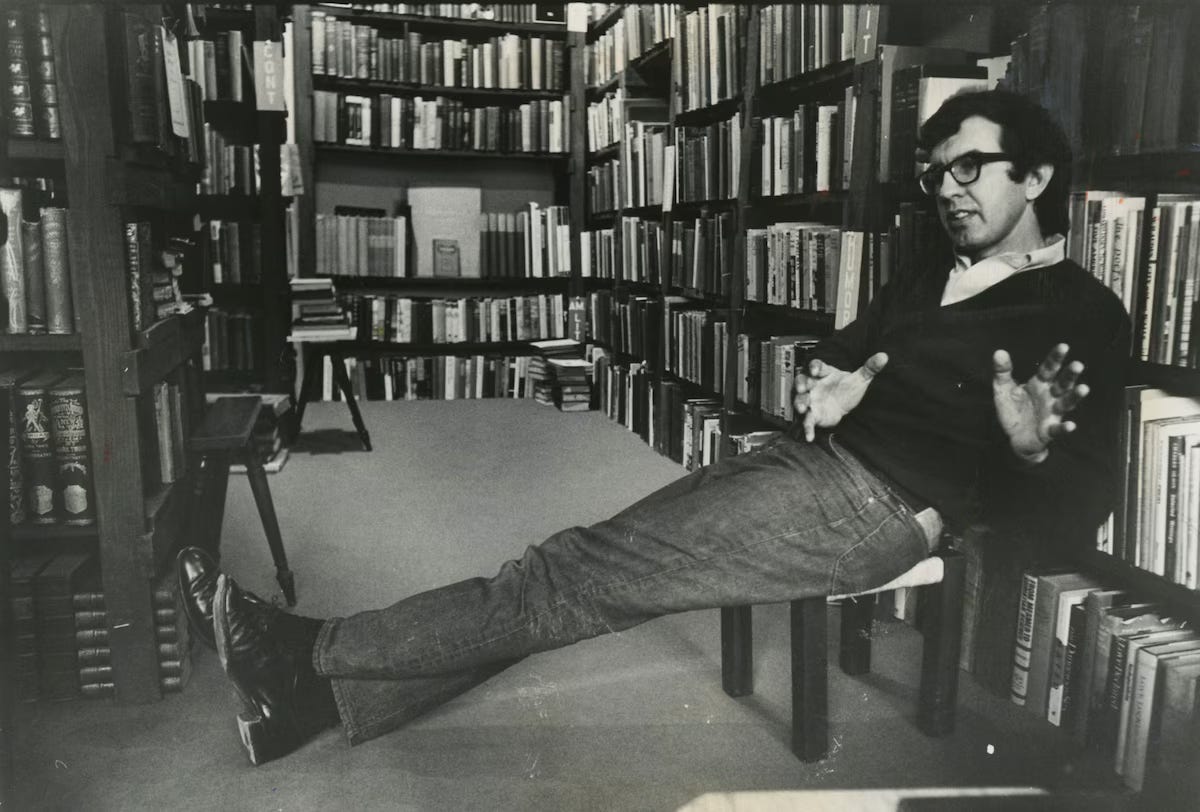

An Interview with Larry McMurtry, Part 2

The mythology of the cowboy has overshadowed oil because it’s so much more poetic. More poetic to see men on horses galloping around roping cattle.

Larry McMurtry

Novelist Larry McMurtry died on March 25, 2021. He was eighty-four years old. Before his death, he had befriended George Getschow, a former reporter for the Wall Street Journal and the Journal’s bureau chief in Dallas and Houston. Getschow met McMurtry not in his capacity as a journalist, but as writer-in-residence for the Mayborn Literary Nonfiction Conference at the University of North Texas—McMurtry’s alma mater. In time, Getschow developed the Archer City Writers Workshop in which student and professional writers gathered in McMurtry’s hometown of Archer City, Texas, and learned the craft of writing from one of the modern masters.

After McMurtry’s passing, his book store in Archer City, Booked Up, was purchased by Chip and Joanna Gaines. They relocated some 10,000 rare books to their hotel in Waco. In late October 2024, they sold the bookshop to the Archer City Writers Workshop. Today, it is now the Larry McMurtry Literary Center.

During the 2013 Archer City Writers Workshop, George and other professional writers and academics sat down with McMurtry to discuss his literature and legacy. In this second of two installments (read the first installment here), McMurtry talks, among other things, about his writing process, the controversy surrounding his criticism of J. Frank Dobie and other Texas writers, and his son and grandson.

Harry Hall (writer whose work has appeared in Texas Monthly): What authors have you enjoyed reading, or what works have you really enjoyed reading recently?

Larry: I’ve reached an age in life when I read very differently. Mostly I’ve read for adventure. Now I read for security. Which means I re-read almost entirely. If I get sent a book that I have to decide whether to try to do the script or something like that, I read it. But for myself I read two authors over and over again. Robert B. Parker, the mystery writer from Boston, and an English aesthete named James Lees-Milne. He left a twelve-volume diary that is one of the treasures of twentieth century English literature. He was a well-known person, a minor writer, a minor critic, yet he knew everybody in the kingdom practically. He worked for the National Trust trying to get them to give up their stately homes, which most of them couldn’t afford by then anyway. He rode all over the British Isles on his bicycle. And the diaries are just charming.

George Getschow: One of the things that distinguishes you from any other Texas writers is courage. You took on the nostalgic writers like J. Frank Dobie and Walter Prescott Webb. And even though you respected their work you also found their work far too sentimental for the reality that you saw before you. You were skewered in some circles for doing that, and yet you did it, and I know that, I’m sure there were costs involved.

Larry: I think I just am better informed. Look at all these books. I have 28,000 books in my home. Most of which I’ve read or at least considered. That’s what I’ve found lacking in Texas literature, and I said it. They haven’t read enough. They haven’t traveled enough. They haven’t seen enough of the world. Gary Cartwright and Larry King and Ronnie Dugger, and a whole gang of quasi-journalists, quasi-writers around Austin. Bill Brammer occasionally wrote really pretty good stuff, but few of them really sustained it. So I was asked to make that speech at a Fort Worth museum, and it caused a little stir.

Bill Marvel (former journalists for The Dallas Morning News): Was there a little bit in it of the young man taking down the mossy old idols with a little bit of pleasure? “Take that, Frank Dobie!”

Larry: It didn’t take ’em down, for one thing. Mr. Dobie I only met once and I kind of liked him. I didn’t have anything against him. The essay on Dobie was written at a time when any criticism written about Dobie was like a criticism of Jesus. But he wasn’t Jesus. He was just a writer. And I don’t think he, himself, participated in his own legend very much. Walter Prescott Webb, no sir, I was able to take a course under Walter Prescott Webb at Rice. He just went right on being Walter Prescott Webb. And I never met or saw Roy Bedichek, another writer that I wrote about in that essay.

Never saw him. Never met him. So I thought it was a reasonable piece, and I was astonished. It was a huge thing, called “Range Wars” or something. The case for it was that thick. It was just one little essay that had long since been forgotten. I think I published it in the Texas Observer. I like literary controversy. There’s not enough literary controversy in Texas. Needs to be more.

Bill: What role does ambition play in a young writer? Did you burn with ambition?

Larry: Yep. I did. I burned with ambition.

Bill: Can you be a writer without that cooking away inside you when you’re young?

Larry: I don’t know. Like I say, I grew up in an easy time, easy to get published. I wrote to three publishers and the third one accepted it. Because in those days they believed in developing talent. Giving an author two or three books and then they start earning money. I was just lucky.

George: I’m going to loop around to the same type of question because I think it’s important for these students. You never shied away from taking on the mythology of the West, taking on the writers who were fostering that mythology, and yet you have a group of students here who have been listening to you talk about the chaos in the industry and the difficulty of writing books, the challenges of becoming a writer. And that’s what they’re here to do. How can they succeed at a time when everything seems to be against them?

Larry: Well, you have to be very persistent. Persistence is the only clue I have. I’ve persisted a lot of years writing five pages a day. Graham Greene only wrote 500 words a day. This is not true of poets. Poets can come and go and get a line today and a line next week or something and have a poem someday, but writers have to be sort of plough horses. Fiction writers just sort of plug away. And most of them limit themselves. I limited myself to five pages.

Harry: Did you ever just get on a roll and go past five pages? Because that happens to me all the time. I’ll be sitting there and think, “I’m going to write X and then your fingers can’t even keep up with your brain.

Larry: Nope. I don’t do that. I stop. It’ll be there the next day and it’ll be better for having had a good night’s sleep. I suppose I must’ve done it sometime, but I can’t remember doing that.

Lori Dann (journalism professor and student media adviser at Tarrant County College): And what about the publishing aspect of it for young writers? That’s the big challenge right now.

Larry: It’s a horrible challenge now and it’s complicated by Amazon and what Amazon has done to publishing. When I started publishing I suppose there were thirty-five legitimate mainline publishers in America, most of them in New York, a few in Chicago, one or two on the West Coast. They’re gone. I think Random House and Penguin have just merged and that leaves five. Five mainstream old-fashioned publishing houses are the outlet for a whole nation of writers. I don’t like it and I don’t know what to do about it.

George: I find it very interesting that you mentioned that you consider one of your favorite books Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen one of your great books. And Walter Benjamin argued that story telling was a vanishing practice.

Larry: Right. Story telling in the classic sense is pretty well gone, I think.

George: It’s fascinating to me that what you consider one of your greatest books was written here at the Dairy Queen.

Larry: Well he makes the point that places where stories are told feed the growth of more stories. And I argued in the book that Dairy Queens sort of became community centers in these little Texas towns. I was trying to figure out the other day when we got our first drive-in. It was called the Wildcatter. It was on highway 29 going out. And I think that was maybe 1948, 9, 1950, somewhere in there. There was a scene set at it in The Last Picture Show and I don’t think it was operating and I think they rented it and opened it up just for that scene. But there’s been a Dairy Queen here for a long time.

You know we’re all crushed here and we’ve had a social catastrophe. The restaurant right across the street from The Spur hotel closed and we’ve had all sorts of gossip about it. Now that it’s closed people have no place to go for breakfast. The Dairy Queen used to be a good place to go for breakfast, because they opened for the oil field workers at 5:30 in the morning. This little café did the same thing. The Dairy Queen now opens at about 11 or so. I think that’s because they can’t get the kids to pass the drug tests. I do. But they’re kind of community centers and they’re places where stories are exchanged.

Bill: How much do you worry about the fate of Archer City? Is it going to be a ruin on the prairie in fifty years?

Larry: Archer City floats on a sea of oil. It’s been an oil town since 1905 when the first gusher hit. It’s been an oil town all through the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, ’60s and it has always been a very, very rich land. Eighty-eight million barrels a day comes out of the ground. The mythology of the cowboy has overshadowed oil because it’s so much more poetic. More poetic to see men on horses galloping around roping cattle or something. People in dozer caps don’t really get much respect, but they’ve been the ones who’ve run the county as long as I’ve been here.

Eric Nishimoto (professor of magazine production at the Mayborn School of Journalism at the University of North Texas): I was here with the last writers’ group that you spoke to. And when I asked you about Archer City then, the only thing that you wanted to say was your quote that you requoted, “a small town full of small-minded people.” But you’ve done so much, you’ve tried to do so much for this town.

Larry: Haven’t changed.

Eric: And you have chosen to live here.

Larry: Well, both of those statements are ambivalent. I haven’t done much for it and I don’t live here. I come in now and then. I live mainly in Tucson. Not entirely, but Tucson is closer to my work, if I have any, in Hollywood. We get over there and get our notes and reach an agreement, or we think we’ve reached an agreement, then we get back home and get to sleep in our own beds. Of course I have a wonderful house [here]. If I didn’t have that house I don’t know if I’d be here much at all.

Bill: What would you tell young aspiring writers about reading—the importance of reading, and what to read?

Larry: I’d tell them that the most important preparation for writing is reading. Certainly for me and most people I know. Trying to imitate the writers that we love to read. That’s what got us all started.

Bill: But you have to read a lot before you find those writers that want to imitate, I would think.

Larry: That’s fine. It doesn’t hurt you to read a lot. In fact, it’s better that you read a lot. You’ll find the right ones.

Matthew Jones (writer): I wondered if you could expand on that a little bit. Earlier you were saying that television writing is booming. I’ve noticed that there are shows like you mentioned, Everybody LovesRaymond, The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, and The Wire, that are essentially visual novels.

Larry: They’re like the nineteenth century novels. They satisfy the same appetite for narrative and family life. The backbone of the nineteenth century realistic novel is the family life. And Tony Soprano is family life in the gangster world. Everybody Loves Raymond is set in the same place, Long Island. Mostly writers don’t write realistic novels about family life anymore.

Matthew: Are there certain television shows that you would recommend?

Larry: I thought Six Feet Under was a brilliant series, but I think The Sopranos right now is my favorite. Wonderful, wonderful series. Everybody Loves Raymond is just about as good.

George: You said in your memoir, A Literary Life, that even though the bookstores didn’t quite live up to your vision for the town that it’s become kind of a seminar town, is the way you described it.

Larry: Yeah. Here we are.

George: I was wondering, in the seminar town we now have these writers who have come here thirsty and hungry to become good writers. And they have. Many of them have gone on to produce books and they’re writing for magazines and so on, and I was just wondering how much—what—consolation you take in that?

Larry: I just don’t think about it. I come down here and talk to them for an hour. I’m glad you’re here and I’m glad you at least get to see a bookstore, which these days is not a guaranteed experience. But otherwise I don’t think about it.

Harry: Why did you invite us down here? Why did you agree to have us here?

Larry: Well, because I feel I owe it to literature, to give a little bit back to books. That’s why I have a bookstore.

Kathy Floyd (writer and managing director of the Larry McMurtry Literary Center): I wanted to ask about James McMurtry. James has taken his storytelling ability and picked up a guitar. Did you think, “Oh I wish I’d picked up a guitar”?

Larry: Both James and Curtis. Curtis is James’ son, my grandson. Both of them have bands and they’ve been very successful. I’m very happy. Myself, I’m not musical, but I think James is an extraordinary song writer and Curtis is going to be just as good. So I’m lucky in having two successful descendants. It’s tricky being the child of someone famous. Yet I’ve been lucky. Both my son and my grandson are doing fine.

Bill: Did you watch this talent emerge in your son with interest and amazement, or was it very suddenly you realized? How did it happen?

Larry: It happened because I was writing a script for John Mellencamp and James came to visit me and took his guitar and was plinking around. John Mellencamp came out and asked him who he was. I think John considers that he discovered James. I don’t know. Maybe he did. But anyway, James played him a couple of songs and Mellencamp decided to produce his first album. It was just an accident. It was a wonderful album.

George: So how does the minor regional writer view his legacy? What is going to be your legacy. Will you talk about that?

Larry: I hope I’m not going to have my legacy just yet.

George: Many years from now.

Bill: No hurry.

Larry: I haven’t the slightest idea. I don’t really think about it. Most writers sink in reputation right after they die, then maybe they come back twenty years later. I think that may happen to me. I hope I’ll come back. I’m pretty sure I’ll sink.

George: Over the years, I know book selling, book dealing, the book business has been every bit as important to you as your writing. Do you see your bookstores and the book business, the work you devoted so much of your life and attention to, becoming an important part of your legacy.

Larry: I don’t think it will. We just talked about my son and his talent, and my grandson and his talent—they’re in music. My grandson is faintly curious about the book—he’s not a book man—and James is even less a book man, although James reads a whole lot more than he wants people to think. He’s a very well read young man.

The book gene, the rare book gene, the book trade gene is a rare gene. Not many people have it. Not many people have it as intensely as I’ve had it. And I think I’d be crazy to think that somebody’s going to pick it up and do what I’ve done. It’s not going to happen.

Okay, folks, I’ve got to go to my next job.

I met George Getschow at a book signing event on August 23, 2025, at Neighbor Books in McKinney, Texas, and asked a question about McMurtry’s opinion of McCarthy, which prompted him to send me this interview, which I lightly edited and is published with George’s gracious permission. Please checkout the Larry McMurtry Literary Center. And if you find yourself in Archer City be sure to drop in at Larry’s bookstore. Better yet, make it a point to find yourself in Archer City.

Y’allogy is an 1836 percent purebred, open-range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is created by a living, breathing Texan—for Texans and lovers of Texas—and is free of charge. I’d be grateful, however, if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber and/or purchasing my novel.

Be brave, live free, y’all.

Just excellent, Derrick. Very enjoyable. Appreciate you sharing this interview with the brilliant Larry McMurtry. He will forever be in my top three author list. - Jim