A Minor Regional Writer

An Interview with Larry McMurtry, Part 1

I think Blood Meridian is a little windy. It loses focus sometimes, although I admire it. And the great passages in it are really wonderful.

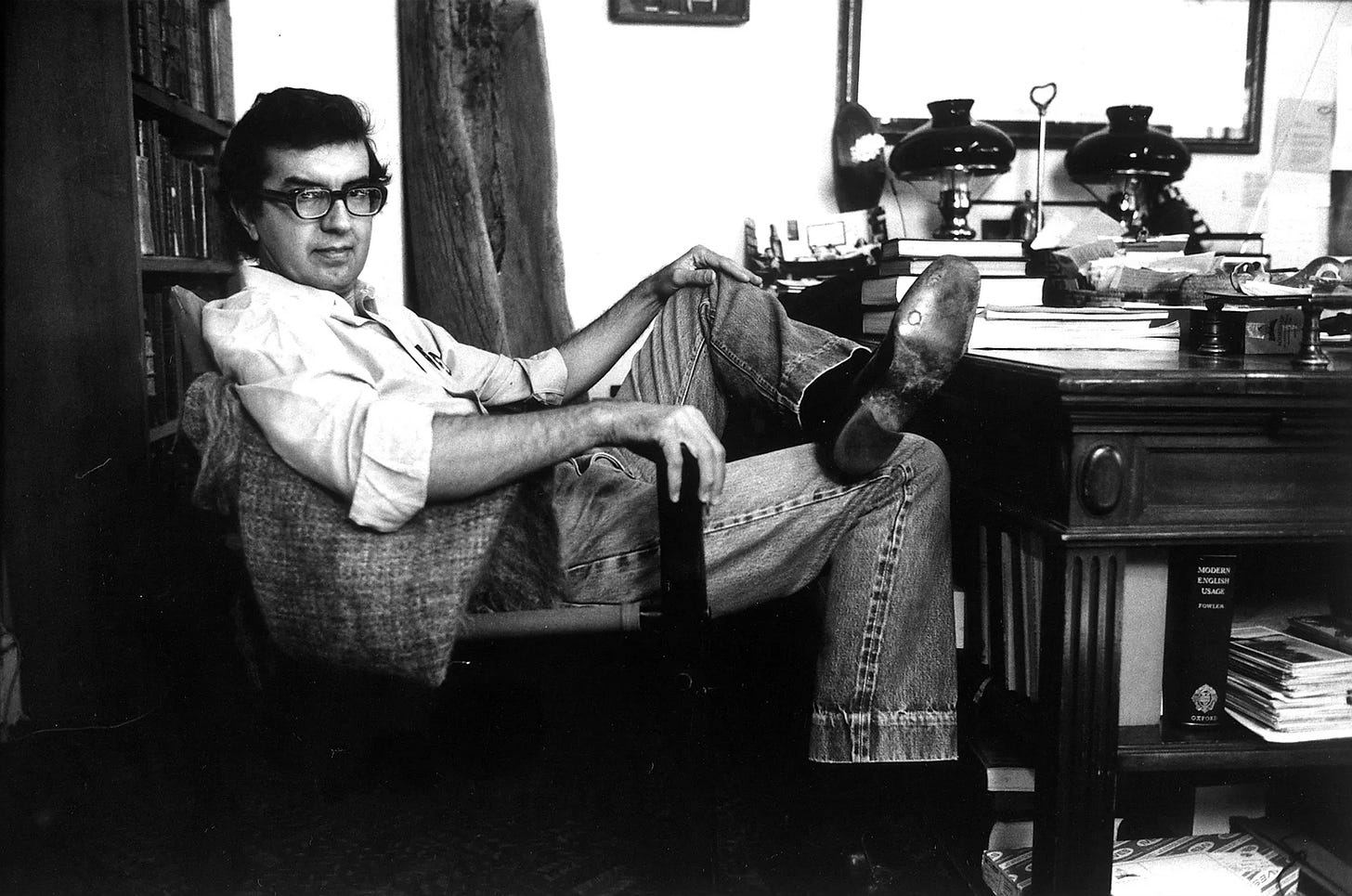

Larry McMurtry

Novelist Larry McMurtry died on March 25, 2021. He was eighty-four years old. Before his death, he had befriended George Getschow, a former reporter for the Wall Street Journal and the Journal’s bureau chief in Dallas and Houston. Getschow met McMurtry not in his capacity as a journalist, but as writer-in-residence for the Mayborn Literary Nonfiction Conference at the University of North Texas—McMurtry’s alma mater. In time, Getschow developed the Archer City Writers Workshop in which student and professional writers gathered in McMurtry’s hometown of Archer City, Texas, and learned the craft of writing from one of the modern masters.

After McMurtry’s passing, his book store in Archer City, Booked Up, was purchased by Chip and Joanna Gaines. They relocated some 10,000 rare books to their hotel in Waco. In late October 2024, they sold the bookshop to the Archer City Writers Workshop. Today, it is now the Larry McMurtry Literary Center.

During the 2013 Archer City Writers Workshop, George and other professional writers and academics sat down with McMurtry to discuss his literature and legacy. In this first of two installments, McMurtry talks, among other things, about minor writers, like himself and Cormac McCarthy, compared to great writers, his critique of Texas and the Western, and the changes Amazon brought to the publishing business.

George Getschow: I’m going to start, even though this is for students. I have to say that this question keeps coming up and people don’t understand. You’ve produced works of literature about the West that rivals anything else out there. Why do you call yourself a “minor regional writer”?

Larry McMurtry: Because there might not be anything out there that’s not minor. In fact, sub-minor is what a lot of it would be. Understand that in the silver light of history almost all writers are minor. A generation just passing might produce five writers that are not minor, might not produce but two or three. I think when you boil down the Mailer-Roth-Bellow generation, there’s not much, really, that I wouldn’t call minor. I think Flannery O’Conner has the clearest claim to be more than minor. She was a great writer.

Bill Marvel (former journalist for The Dallas Morning News): What about Cormac McCarthy? You didn’t mention him in the pantheon.

Larry: I think that his early books are not very good. His great book, if he has a great book, is Blood Meridian, but I’m not sure it alone lifts him out of the category of being a minor regional writer. I like, for myself, No Country for Old Men better than Blood Meridian. I think Blood Meridian is a little windy. It loses focus sometimes, although I admire it. And the great passages in it are really wonderful.

I think I should say a few more things. Literature moves on from one generation to another generation because of the work of minor writers. People like Dickens and Thackeray that looked like major writers when they were writing, they don’t look so major. They’re not beyond reach. Literature is fed by minor talents. Mine is, certainly.

If I had to point to two books that might lift me out of the minor catalogue it would be Duane’s Depressed and Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen. I think those are both really good, really, really good books. A lot of the rest of them are good, but they’re not earth-shaking. It’s okay to be minor. In fact, if you can be minor you’ve made a considerable achievement, because most people don’t register on the scale of minor or major at all. So I’m not worried about it.

George: You’re one of the few Texas writers who’s looked at the state unsentimentally.

Larry: That is true. I’ve tried as hard as I could to demythologize the West. Can’t do it. It’s impossible. I wrote a book called Lonesome Dove, which I thought was a long critique of western mythology. It is now the chief source of western mythology. I didn’t shake it up at all. I actually think of Lonesome Dove as the Gone with the Wind of the West.

Bill: You’ve dedicated your life both to books and to writing about the West. There’s not a whole lot about the West going on. Certainly Westerns have died as a genre. What is the fate of writing about the West and of books? And do you fret about these things that are disappearing?

Larry: You bet I do. I fret about these things that are disappearing. I don’t know that the Western is. But I’ll tell you what. If anything has destroyed the Western genre it’s The Legend of the Lone Ranger, which I wrote the first script for twenty-six years ago. [It lost] $375 million. Who knows when they’ll make another Western. But I don’t think the Western as a genre is gone. We are working on a couple. And I’ve written another novel that’s a Western and it will be published in the spring. [The Last Kind Words Saloon, published by Liveright in 2014.] It’s still there.

But the big, big, big changes. I’m having a conflicted tussle with Amazon because what they’ve done to the book business is horrible. It’s just horrible. It’s destroyed conventional publishing. As much as I hate them, they came to me the other day with an offer to make a pilot that Diana Ossana and I wrote five years ago. And it drifted around. It went to HBO, they got it and paid for it and then they put it on the shelf. It went to 20th Century Fox and they put it on the shelf. Amazon wants to do it and they have the moxie to do it. They have so much money it’s incredible, and they can do whatever they want to do. They released fourteen pilots to the mainstream in a week. Nobody else can do that.

What I see is everything has become television. Television is smarter than movies, it’s infinitely cheaper than movies, it’s more flexible than movies. I think of the major stuff that’s come out on movies and television, say, in the last decade. Something like Everybody Loves Raymond and The Sopranos. They’re great series, you know? There’s nobody writing novels that good right now. I like them very much.

I’m not sure about the book. The book is a pretty solid technology in itself. It’s pretty hard to better it, as Barnes and Noble has found out to its sorrow. They lost $5 billion. They’re just a bookstore chain. I don’t think bookstore chains can afford to lose $5 billion and stay viable. And it’s extremely crucial that they do if they can. I have this book coming out in March or April. If Barnes and Noble is gone, where are they going to sell it? Where’s it going to be seen? I’d like to feel that the people who say the book is doomed are wrong, but I can’t really say that yet.

George: I’m intrigued that your last book was a Western about Custer, and you said you’re coming out with a book in April that is going to be a Western. It sounds as if you believe Westerns are going to be around for quite a while.

Larry: Oh, I do. I don’t think you can sink the Western. Well, Custer is a flashpoint with me. It wasn’t at all what I intended. I intended to write a companion to my Crazy Horse, a short biography or something like that. I never intended for it to be a coffee table book with hundreds of photographs. There was a change of executive structure at Simon and Schuster. The new person didn’t want it, and so they held it a year and a half, they tarted it up with all those photographs and I’m very disappointed in it. But that doesn’t mean the end of the Western. There will still be Westerns.

Bill: So there is room to write about the West for young writers?

Larry: Sure. The West is an inexhaustible subject, I think. I don’t see any slackening of interest in the West. I get asked to blurb or review Western books almost every week, two-three a week sometimes. People are still curious about it. Most people don’t know much about it. I don’t know much about it for that matter. But I know enough to be reasonably accurate.

Amy Burgess (writer whose work has appeared in The Dallas Morning News): You’re one of the few writers who’ve had equal success in the different genres, with TV and movies and books. Which ones get you the most excited when you have a new project that gets picked up?

Larry: They’re so different, it’s very hard to compare them. I’ve written thirty-two novels. I can’t say that I get excited when I start to write a novel. I get to work, but it’s not a daily thrill. And neither is working in movies. Working in movies has become harder and harder and harder. I’ve had three or four very successful movies. Average time on making those movies was ten years. Ten years to make Terms of Endearment, ten years to make Brokeback Mountain. It doesn’t come quick. You have to get the money. and to get the money you have to get the actors that can bring the money. It’s very slow.

We have several projects right now that I don’t understand why nothing is happening. Two years go past, no checks come in the mail. It just sits there. We have a project with Ridley Scott right now that’s set in this part of the country. So, there are stories out there. But it’s really, really hard to make Westerns. The thing that’s so hard about it is that they involve animals—cattle, buffalo, horses—and animals are so expensive. The reason it’s more likely to happen on television—the reason Lonesome Dove was on television instead of film—is that it’s so much cheaper. It’s all about money.

I’m kind of apprehensive. I’ve done this for a long time. I wrote my first screenplay in 1961. I know the studio world pretty well. I know the acting world pretty well. I know my way around Hollywood pretty well. I just think the movies have backed themselves into a corner. You can’t go on having $375 million productions. They don’t have that kind of money anymore. They wish they did, but they really don’t.

What they’re doing now, the last three projects we’ve been offered as screenwriters, all of them wanted us to write a spec script first. That means write a script that will enable them to get enough money to pay for the script. We can’t do that. Other than writing a good script, we can’t help them get the money. Or at least we’re not going to.

I’m always grateful that I’ve worked in a cheap art, which is fiction. Say I do want to write a book about Billy the Kid. It’s not hard. I don’t have to invest a whole lot into it. I have a book or two about him and that’s all I need to get started. And enough rent and grocery money to get three or four months while I write it. That’s real cheap. In the movies to even get to the first step, which is some kind of outline of what the story will be, you’re up to half a million right away.

So, I’m very lucky. I got started just at a time when it was possible to get a book or two published and it didn’t cost so much. More and more books are being self published, and being self published credibly. We had one here in town, Jim Black wrote a novel called, There’s a River Down in Texas. He published it himself and Viking liked it so much that they published it in New York. Self publishing is not necessarily the end of the road. It can be the beginning of the road.

Amy: Would you ever self publish?

Larry: Yeah, I was just about to self publish this weird little novel, then somebody bought it, strangely enough. [The Last Kind Words Saloon.] To my intense surprise. Someone bought it and saved me the trouble.

Harry Hall (writer whose work has appeared in Texas Monthly): Why were you going to self publish?

Larry: Because I didn’t think anybody wanted it. It’s a quirky, very quirky book. It’s a form that you don’t see any more, which I call a pastiche—which is somewhere between realism and parody. My own publisher had been so negative about it that I thought, Maybe they’re right. Maybe it is awful. Then two years passed and I got it out and read it, and I rather liked it. I told the agents to say bye-bye to Simon and Schuster and shop it around a little bit. It sold instantly.

It’s an end-of-the-West Western. Most of the Westerns that you read or have read are end-of-the-West Westerns. This one is just a little more clearly an end-of-the-West Western. I felt that there were stories and people like Charles Goodnight, people like Wyatt Earp, people like Buffalo Bill, that could use a little coda of some kind, one more pass. So I did it. I think it’s pretty good. I don’t think it’s a world masterpiece, but it might be. You never know for sure.

Lori Dann (journalism professor and student media adviser at Tarrant County College): Can you talk about your writing process?

Larry: It’s simple. I write five pages a day in the early morning, usually through by 9 or 9:30. I’ve done this over my whole career, and five pages a day adds up. I’ve filled several warehouses with all the writing I’ve done. Because I’ll do three drafts, seven or eight drafts of screenplays usually. A lot of paper gets typed on.

Lori: Do you have people who read that for you before you submit it?

Larry: My writing partner Diana [Ossana] reads most of my books. She’s a very good movie producer. She reads with an eye to see what’s going to work and what’s not going to work, and what’s going to be too expensive and what’s not going to be too expensive. Almost everything is too expensive.

George: Do your drafts consist of cutting?

Larry: Yeah, one is cutting out mistakes, repetition, stuff like that. The other, the last, is for style. I give it a little polish.

Bill: Do you ever write something and realize within a day or two that it’s really dead? That it’s not going to come to life and essentially you’ve wasted two or three days on a trail that plays out?

Larry: No, that doesn’t happen to me much. I usually write what I think I’m going to write. I don’t start until I have an ending in mind. It’s much easier to write toward an ending than it is to write away from a beginning. You see two people in a situation like the closing of the picture show in a small town, that’s an end to some story, or a lot of stories maybe. And it’s something you can write toward.

Bill: So you must spend a long time letting the plot kind of unroll in your mind.

Larry: It depends on circumstances. I wrote—and I don’t remember what year this was—I wrote a little novel called Cadillac Jack about an antique scout. The world of scouting has always interested me. I’ve been a book scout for a long, long time. I thought that was it. I thought it would pay my income tax. It was the first of March, or late February. And by golly, it didn’t pay my income taxes. And I wrote another novel between then and April. It’s called The Desert Rose. It’s one of my very favorite books of mine. It’s a beautiful story about a great show girl in Las Vegas in an era when show girls were being phased out. And I wrote it in three weeks.

Amy: Do you ever have writer’s block?

Larry: Never have, fortunately. I wrote it in three weeks. I’ve written two or three books in very short periods.

Amy: That’s pretty impressive to think, “I’m going to pay my taxes, so I need to write a book,” and just be able to sit down and do it.

Larry: I wouldn’t do it every time. You get away with stuff like that once.

Bill: I’m interested in the internal process of plotting a novel. You get an idea of maybe a situation, or maybe the ending, and then as you go through the following days, you stand in front of the mirror shaving or you’re doing something else, and suddenly an incident pops into your mind? Or how do you begin to assemble that plot?

Larry: You know, I don’t think about it at all until the next morning when I get up and write my five pages. I don’t think about it all day. If it’s a screenplay I usually get it to Diana by 8:30 and she works on it as long as she wants to and I don’t have anything more to do with it until the next day. Same way with fiction. I don’t think about it. Of course I imagine that I’m thinking about it somewhere in my subconscious, but I’m not ever aware of thinking about it at all during the day.

Bill: Is one of you good at dialogue and the other good at plot? How do you do you divide that up?

Larry: Yes, she’s very good at structuring and I’m very good at dialogue. For movies, that is.

Bill: So these students are going to be talking about dialogue later today. What would you tell writers about writing dialogue?

Larry: Well, I would say trust your ear. I trust mine. Maybe your ear isn’t trustworthy. Then you’re in trouble. I don’t know. I don’t think there’s any set way to do it. You either have an ear or you don’t. I don’t know many people who have ever acquired an ear.

Amy: Kind of like music?

Larry: Yeah, kind of like music.

I met George Getschow at a book signing event on August 23, 2025, at Neighbor Books in McKinney, Texas, and asked a question about McMurtry’s opinion of McCarthy, which prompted him to send me this interview, which I lightly edited and is published with George’s gracious permission. Please checkout the Larry McMurtry Literary Center. And if you find yourself in Archer City be sure to drop in at Larry’s bookstore. Better yet, make it a point to find yourself in Archer City.

Y’allogy is an 1836 percent purebred, open-range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is created by a living, breathing Texan—for Texans and lovers of Texas—and is free of charge. I’d be grateful, however, if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber and/or purchasing my novel.

Be brave, live free, y’all.

That was a great interview - thanks for sharing it.

Hard for me to believe that it’s been four years since LM died.

Terrific stuff. Thanks for sharing, Derrick. - Jim