What Is a Texan? Part One

Then the trouble began.

Martha Rash

When my wife Christy and I started dating in high school I knew she was the gal for me. I joined her for the annual Rash family Christmas breakfast our first Yuletide together. In those days it was a packed affair with aunts and uncles and cousins, along with Christy’s folks and two older brothers. All of this was overseen by Grady, the patriarch, whom everyone called Boss, and the matriarch, Martha, affectionately known as Gommie.

Don’t let the grandmotherly name fool you. She was a force to be reckoned with and not to be trifled with, especially when it came to grits and Texas. Like a newborn calf trying to to find its footing, I was attempting at that first Christmas breakfast to figure out the family dynamics. I didn’t want to do or say anything that would make a poor impression on the family I hoped to become a part of one day. Little did I know it wasn’t something I said or did that caused me to plant a foot in a pile of manure in Gommie’s eyes. It’s what I refused to do that did that.

I passed on her grits.

No sooner had I moved on to the bacon and sausage than Gommie began questioning my upbringing and whether I was a true Texan. I knew an appeal to the fact that my mother never served grits would be unpersuasive, but gambled that establishing my Texas bonafides would extract me from the manure pile. I knew from Christy that Gommie’s ancestors had come to Texas in 1829, as part of Austin’s Little Colony. I also knew she was a member of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas. So, to keep myself from being kicked out the door, I told Gommie it appeared I might have an Alamo defender in the family line. Well, that’s all it took. Now and forever more I could turn my nose up to her grits—and could have married her granddaughter on the spot.

Gommie served as the president of the DRT during the Texas Sesquicentennial, but remained active many years after her term in office. What follows is a speech she delivered on a subject she was imminently qualified to address: “What Is a Texan?” These remarks were presented on October 22, 1991, to the wives of certified public accountants at Brookhaven Country Club in Farmer’s Branch, Texas.

The text has been edited for clarity and length.

You have heard that I am a member of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas. I’d like to tell you a little about that organization [since] I probably will refer to it during my talk and I’d like for you to understand what it is. The Daughters of the Republic of Texas is the oldest women’s patriotic organization in Texas and one of the oldest in the United States. We were organized in 1891. Our members are descended from a man or woman who was in Texas before or during the time Texas was a republic. Among our objectives are the perpetuation of the memory and spirit of Texas and the encouragement of historical research into the earliest records of Texas, especially those relating to the revolution of 1835.1 We have been responsible for saving the San Jacinto battleground and marking its important areas. We are custodians for such Texas state buildings as the French Legation Museum in Austin. This is the oldest standing house in Austin and was the French Embassy to the Republic of Texas. We are also responsible for saving the Alamo from destruction when someone wanted to build a hotel on that spot. The State of Texas gave the Daughters custodianship of the Alamo 86 years ago.2 We have restored and maintained the Alamo from the funds the DRT raises and from donation. We have neither asked for, nor received, any funds from the State of Texas. Our organization has marked many historic spots including the only known marker left standing designating the boundary between the United States and the Republic of Texas. This is between Texas and Louisiana. I was fortunate to have served as President General during our Sesquicentennial celebration. It was an exciting time and an opportunity to meet many distinguished people on the state, national, and international level. The DRT is celebrating its 100th birthday this year.

Texans are a curious lot. From the very earliest days of Texas right down to J. R [Ewing of the television show Dallas], people have been curious about what makes a Texan the way he is. There is something special and different about Texas and Texans. Texas is a state of heart and mind. I’m not going [into] facts and figures, a geographical picture or a travelogue of Texas. I am not giving you an apology for this state and its people. For some reason people around the world have been interested in or curious about us. . . drawn to Texas by [a] mystique. . . . When you are traveling and someone asks if you are from Texas, do you find yourself drawling a little more, saying y’all and yep just a might more? You know the saying, “Never ask a person where he is from. If he is from Texas he will tell you. If he isn’t, don’t embarrass him.” Well, I have never been one to pass up a challenge so, how many native Texans are here today? Good, you should already know your Texas history. The rest of you, even though you weren’t born here, are Texans also, either by choice or because the boss transferred you here. Whatever the reason, we’re glad you’re here and we welcome you. Given time you can’t help but love us! You have heard us say, “If you don’t like the weather here just wait a few minutes.” Well, that goes for our land, too. I imagine Texas was a mind boggling area for some of our ancestors. We have the beautiful pine forests of East Texas, our coastal lands, our tropics, our mountains, and our flat prairie lands. Take your choice.

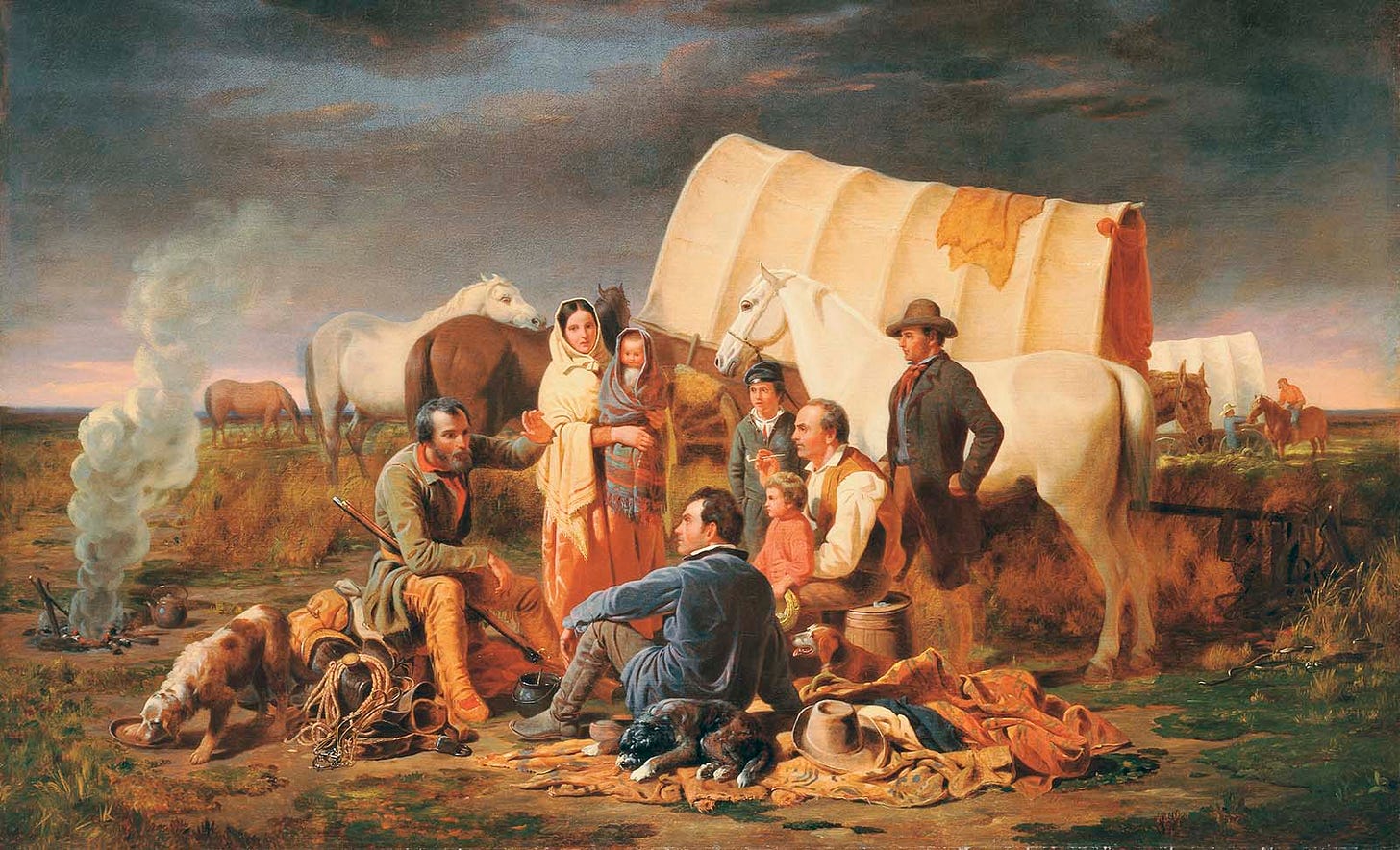

Life is a little easier now than it was when Stephen F. Austin received permission to bring his first three hundred families to Texas. When he was granted permission by the government in 1820 to colonize Texas, it was as much to Mexico’s advantage as it was to Austin’s. The Spanish tried to establish missions and then the Mexican government later tried to bring in colonizers but neither had too much success. The Mexicans would not settle in Texas because of Indian raids. The only successful town was San Antonio de Béxar. In order to get the Indians subdued or moved out the Mexicans decided to let Anglos come in and establish colonies. Austin’s first colony was known as “the Old Three Hundred.” They settled along the Colorado River. They didn’t come in one big body, but came a few at a time. We have heard how the people decided to come to Texas—loaded their wagon and wrote GTT, “Gone to Texas,” on their cabin or house and left. Well, it didn’t happened quite like that. . . . Many times they had to wait until they could liquidate property holdings and sell their household goods to get enough money for the journey. The money was used to buy supplies and a strong wagon that would carry the many hundreds of pounds of supplies. It was best if the wagon was built of hardwood for durability. . . . What they used for the trip to Texas was the classic Prairie Schooner. It was a [small], [light] wagon with straight lines. Typically the emigrants used a firm wagon with a flat bed about ten feet wide and straight sides two feet high. One young son recalled that his father worked for months to build a wagon sturdy enough to withstand river crossings. They had to buy food supplies at the start of the journey such as flour and sugar, as well as bacon, coffee, salt, tallow, rice, chipped beef, tea, dried beans, dried fruit, baking soda, and vinegar, if they could afford it. They also had to have basic kitchen ware: a kettle, frying pan, coffee pot, tin plates, cups, knives, and forks. . . . One of the main items would be a supply of powder, lead, and shot. They also needed rifles and that was an extra sixty to seventy dollars. One of the biggest expenses of the journey was the oxen or horses to pull the wagon.

There was always the need for cash on hand throughout the course of the journey to replenish supplies that were used, to pay for charges if there were ferrymen at river crossings, to buy replacements for wagons that broke down or oxen and horses that had gone lame, and also to buy food for their first winter in a new land. . . . Wagon tongues, spokes, axles, and wheels were liable to break [so] most emigrants traveled with spare parts slung under the wagon beds. Grease and tar buckets, water barrels and heavy rope were essential equipment. It was all tied on the sides of the wagons. As wagons deteriorate from overloading or breakage, repairs were made. The coverings of the wagons were a strong and sometimes double thickness of canvas, as rainproof as oiled linen, muslin, or sailcloth could be made. We have all seen the Western movies where the wagons come to a river crossing. Do you remember how they did it in Hollywood? If the river was more than wheel deep they would crack the whip and drive the animals into the water and the wagon would float across. Not so in real life. If pioneers hoped to keep goods in the wagon dry, they made camp and unloaded everything from the wagon. Remember, I told you they carried a tar bucket on the sides of the wagon? They heated the tar bucket over a fire and caulked all the slats on the bottom and sides of the wagon to waterproof it for the crossing.

For the men, the routine chores of the journey included driving the wagons and swimming the cattle across innumerable rivers. There were always wheels to be taken off and soaked overnight, others to be greased, broken locks to be tightened up, whiplashes to be spliced and cut. They also had, at times, to watch for and protect their families from raiding Indians.

Routine chores for the women included cooking in the wind and rain, using weeds or buffalo chips to make their fires. If river waters were high, then everything inside the wagon, supplies and possessions, might have to be unloaded, placed on rafts, taken across, and repacked again on the other side by the women and children. Every bit of ingenuity and physical stamina that women could muster was needed. Have you ever seen a picture in that era of a beautiful woman in Texas? The women who pioneered in Texas were not much for having their hair styled or their nails manicured. Their hair was usually severely pulled back and finished with a knot or braids. I’m sure their nails were not long and shapely. Their dresses were homespun and colored with dye made from berries or minerals. It was later, when the towns and social life were established, that the curls and lace made their appearance.

Life was hard in those early years. . . . The women worked hard beside their husbands, bore many children, and welcomed any and all to sit at their table and partake of their food. Today, we still practice one of their rituals. They did the laundry for their families. They called it “wash.” I don’t mean they dropped the clothes in the automatic washer, threw in the soap, and left to keep a luncheon date. Their way was to haul water by buckets, either from a stream or a well, build a fire outside to heat their water, and used some sort of board to scrub their clothes with the lye soap they had made. All this with a rifle close at hand to ward off Indians. It was a wife’s duty to protect home and children when her husband was not close by. . . . She did her cooking in the fireplace of her home or over a fire built on the side of the trail. . . .

It is said that the Texas men were rude and on the wild side until their families started to arrive, bringing the influence of the women and their refining traits. Sam Houston was in Philadelphia in 1851, and he brought up the subject of the rights of women in Texas when he addressed an audience in a church fund-raising speech. He was rankled at what he considered longtime, unfair slander of the state’s good name. I quote, “I know very well that Texas had a very bad reputation and that she had not the sympathies of everybody because it was said that all the vagabonds and all the culprits that fled from this country went to Texas.” To continue,

A new country is where men of enterprise, of daring, of rude and rough character, resort. Females will avoid the perils of the tempestuous life. The men that congregate there have not the restraints of society upon them; they trample down all the higher refinements of ladies, who are the chasteners of morals and the purifiers of the heart. Their company inspires a love of property and virtue, and whatever is noble, generous, gallant, brave or honorable.

We had not their society; and when evening came, after the day’s toil was over, whether in their village or in the country, there was no female circle for a man of genius or of spirit to resort to and pass the evening. . . . He loses their chastening influence, and becomes rude and wild and either gives way to champagne and debauchery of some kind, or to the card table.

To bring in a better class of women and their “chastening influence” to Texas the state was the first “that took up the great subject of homestead possessions to the ladies. Our laws are that, if a lady marries, her husband has no control, without her consent, over her estate, he cannot dispose of any portion of it, nor can it be taken for the satisfaction of his debts, incurred either before or after marriage; if he dies owning the whole estate, and she owns nothing, she has her homestead and improvement, and farms, protected by the amount of 200 acres, or to $2,000.00. That cannot be attached. Now, if you can beat that, I will give up.”3

In the early 1820s and 30s when the families started coming to join Austin and other empresarios in taking up land in Texas, the women brought some change in their areas. Men may have remained rough when they were not around women but they respected women and the men cleaned up their language when a woman was present. Still, life was very hard. They didn’t have time to wear latest styles and the fine clothes of the Eastern United States. Men in Texas wore homespun or clothes made from the skin of animals. The leather pants, jackets and hats served them well in the life they lived in the wilderness. They were never without a gun or two.

Now we know why the colonist came to Texas. The Mexican government needed them to settle the area and drive out Indians. They and the Spaniards before them had been unsuccessful. They opened the territory to the Anglos under the Constitution or agreement of 1824. This had certain restrictions. [Colonists had to obey] Mexican laws and embrace the Catholic religion. On this last [point] the Mexican government looked the other way. As an inducement, they were free from all tithes, taxes, [and] duties for six years. The colonists came to Texas for the promised land grants and a chance to start over. I must tell you here of one of my ancestors. She came to Texas in 1829 and was married when she was of age. In fact, she married five times. Always to the same man. Every time the government changed, she insisted on another marriage ceremony. She was afraid she wouldn’t be legally married. . . .

When Stephen F. Austin received permission to colonize, he too was willing to become a Mexican citizen and obey their laws. The people who applied to join his colonies had to have a letter of recommendation concerning their character. When the conditions of the Constitution of 1824 were drawn up, this, too, was agreeable to them. They had every intention of observing the contract. When Santa Anna led a revolt and became head of the government, he was heading the Federalist government. Later, he abruptly changed and was advocating a Centralist government and ruled as a despot. The Constitution of 1824 was broken and it became very hard on the colonist. Then the trouble began.

What Is a Texan? Part Two will be published next week.

Notes:

1 Though the Texas Revolution officially began on October 2, 1835, with the battle of Gonzales, I believe she may have meant the Revolution of 1836, since the most significant events of the revolution took place during that year and that’s generally how the revolution is known.

2 The Alamo remained in the hands of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas until 2011, when the Texas legislature transferred their responsibility to the General Land Office. The GLO initially contracted with the DRT to continue day-to-day operations, but in 2015 the GLO terminated its contract with the DRT and transferred responsibility for daily operations to the non-profit Alamo Trust.

3 Sam Houston, “A Lecture on Trials and Dangers of Frontier Life,” speech delivered at Musical Fund Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, January 28, 1851, quoted in The Writings of Sam Houston, 1813–1863, vol. 5, ed. Amelia W. Williams and Eugene C. Barker (Austin: The University of Texas Press, 1941), 277, 278–9.

The piece you just read was 1836% pure Texas. If you enjoyed it I hope you’ll share it with your Texas-loving friends to let them know about Y’allogy.

As a one-horse operation, I depend on faithful and generous readers like you to support my endeavor to keep the people, places, and past of Texas alive. Consider becoming a subscriber today. As a thank you, I’ll send you a free gift.

Find more Texas related topics on my Twitter page and a bit more about me on my website.

Dios y Tejas.

Thanks for another great slice of Texas history! 🤠 ⭐