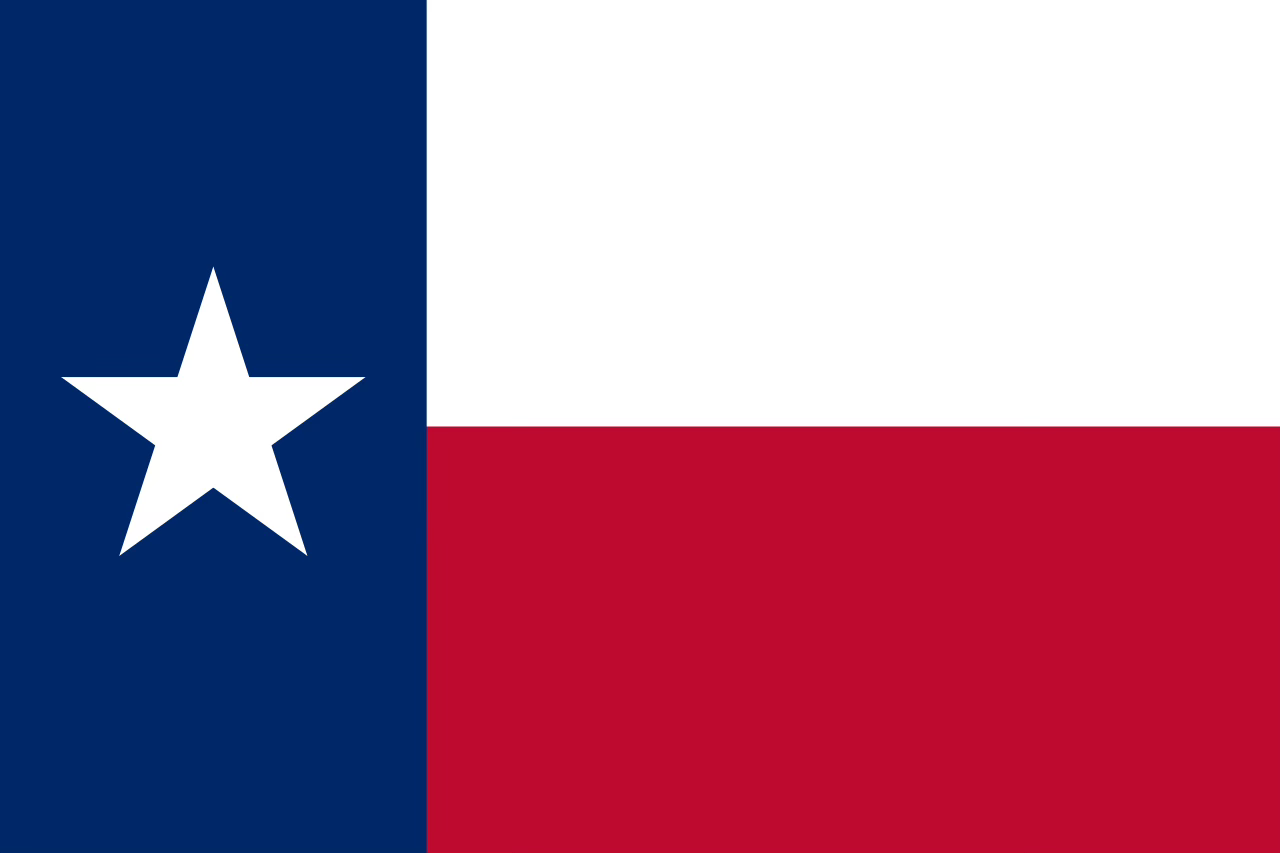

Was Texas the Only Independent Republic Admitted to the Union?

Y’allogy is an 1836 percent purebred, open-range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is free of charge, but I’d be grateful if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber.

Everywhere in the state wonderfully and slightly self-conscious patriots would ask me what Texas reminded me of most. As a rule, I would answer “Vermont.”

John Gunther

In the waning days of World War II, journalist John Gunther crisscrossed the country, visiting all of the then forty-eight states of the United States. Shortly after war’s end, he published his reflections on his American tour: Inside U.S.A. A recurring theme on his travels throughout Texas was the braggadocio of Texans. In Forth Worth, while the war still raged, he spied a sign: “buy bonds and help texas win the war.” He also noted that Texans love to tell the tallest of tall tales. He wrote,

Texas is the place where you need a mousetrap to catch mosquitoes, where a man is so hardboiled that he sleeps in sandpaper sheets, where the grapefruit are so enormous that nine make a dozen, where Davy Crockett fanned himself with a hurricane, where a flock of sheep can get lost in the threads of a pipeline, where canaries sing bass, where if you will spill some nails you will harvest a crop of crowbars, were houseflies carry dog tags for identification, where if you shoot a javelina (peccary) it will spit your first bullet back, then race it toward you, and where that legendary creature Pecos Bill, the Texas equivalent to Paul Bunyan, could rope a streak of lightning.

Texas is is the stuff of legend and myth. I’m sure other states and regions have their share of myths and legends, but since Texas is my gathering ground I’ll stick to wrangling the legends and myths of the Lone Star. One of the most persistent myths, despite all attempts to kill it, is what I call the myth of the exlusividad de la República de Tejas—the myth of the exclusivity of the Republic of Texas. It’s the belief that Texas was the only state in the Union that was its own country first.

As an 1836 percent purebred Texan—head, heart, hide, and hoof—it pains me to say this is just not so.

When Gunther travelled through the Lone Star state he was often asked which state reminded him of Texas the most. “As a rule,” he wrote, “I would answer ‘Vermont.’” Vermont? Vermont is nothing like Texas. Texas is gigantic compared to Vermont. At least twenty-eight Vermonts could fit inside of Texas’ borders. Texas is also more geographically diverse than the evergreen state of Vermont. Texas has piney woods, Gulf coasts, rolling hills, high desert mountains, and plains. And I haven’t even touched on the cultural diversity between the Lone Star state and the Green Mountain state.

But Vermont, like Texas, “has a very special individuality and character,” Gunther noticed. He also noted: “Vermont too was . . . an independent republic for some years.” It’s true.

The Vermont Republic

On January 15, 1777, delegates from twenty-eight towns met in what is now called the Old Constitution House in Windsor and declared independence from jurisdictions and land claims of the British colonies of Quebec, New Hampshire, and New York. Sometimes referred to as the State of Vermont, it remained independent for the next fourteen years, though it never received diplomatic recognition from foreign powers. On March 4, 1791, Vermont was admitted to the United States as the fourteenth state.

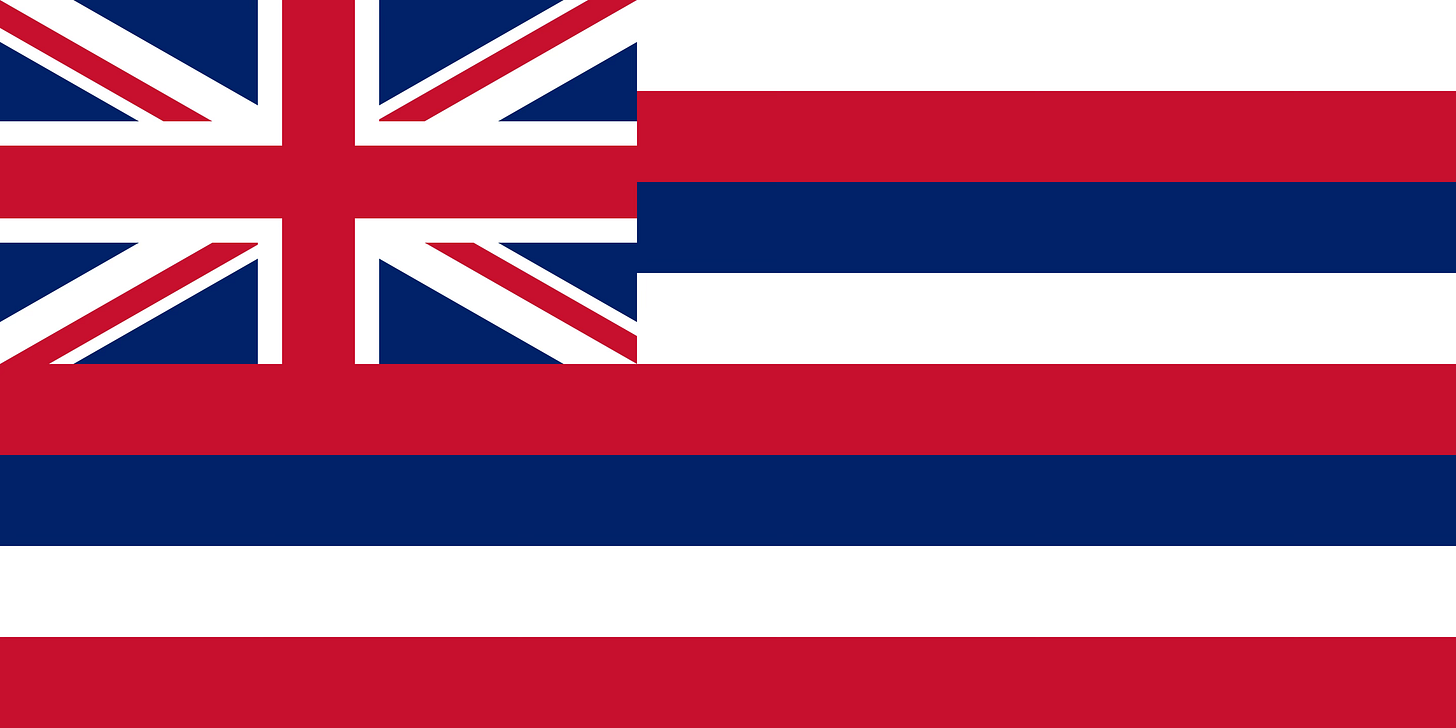

The Hawaiian Kingdom

Vermont and Texas weren’t the only states that were independent countries before joining the United States. So was Hawaii. It was actually a kingdom and a republic. From 1795 until 1893 Hawaii was under the rule of a monarch. Then, after a provisional government (1893–1894), Hawaii became an independent republic (1894–1898), when it became an American territory. Hawaii remained an American protectorate for the next sixty-one years, until it became the fiftieth state to join the Union on August 21, 1959.

The California Republic

It hardly seems worth mentioning—and is a blow to my Texcentric ego—but technically California was also an independent republic, even if they didn’t have a declaration of independence and it lasted only twenty-five days.

The annexation of Texas by the United States on December 19, 1845, was a match to an international haystack. Not only did the annexation of Texas lead to the conflagration of the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), it also sparked an uprising in California, known as the Bear Flag Revolt (so named when American rebels adopted a flag emblazoned with a grizzly bear and red star against a white field, which became the basis of California’s modern flag adopted in 1911). On June 14, 1846, thirty armed Americans entered Sonoma, a small town in Alta California, Mexican territory. They met no resistance. When they encountered the Mexican commander, Colonel Mariano Vallejo, he invited the Americans to share a brandy as part of his official surrendered.

Twenty-five days later, Commodore John Slot and his U.S. fleet captured Monterey on July 7, 1846, declaring California a part of the United States. The Bear Flat Revolt (the California Republic) officially ended on July 9. Four years later, California became the thirty-first state on September 9, 1850.

So you see, Texas wasn’t the only independent nation to join the United States. But in good old Texas fashion we still have bragging rights over Vermont, Hawaii, and California. None of the other republics gained independence through armed conflict. They can boast of no Alamo-like heroics, Goliad-like tragedies, or San Jacinto-like grandness. And perhaps with the exception of Hawaii, neither did they receive international recognition, while Texas did. So, in the words of one Texan, all these other republics are “bush league by comparison.”

John Gunther, Inside U.S.A. (New York: Harper Brothers, 1947), 815–6, 820

W. F. Strong, Stories from Texas: Some of Them Are True, vol. 2 (Columbus: Gatekeeper Press, 2021), 127.

The 1836 Percent Y’allogy Guarantee: This newsletter is created by a living, breathing Texan—for Texans and lovers of Texas. It exists thanks to the generosity of its readers. To ensure it continues, I invite you, if you’re able and haven’t already done so, to ride for the brand as a paid subscriber, give the gift of Y'allogy to a fellow Texan, or purchase my novel.

Much obliged, y’all.

25 days? LOL. That doesn't count. And an independent republic would have to have diplomatic recognition from other countries or it isn't really an independent republic. I appreciate the attempt at humor! :)

My direct line traces back through Vermont. They were there at the time of that republic, I think.

Something to check out!

Thank you, kindly.