The Sage of Idiot Ridge

If I thought a love affair would give me six months of intense pleasure but that this woman I had a real affinity for would not be in my life ten years from now, I would walk around the love affair. . . . I would go for the long-term friendship.

Larry McMurtry

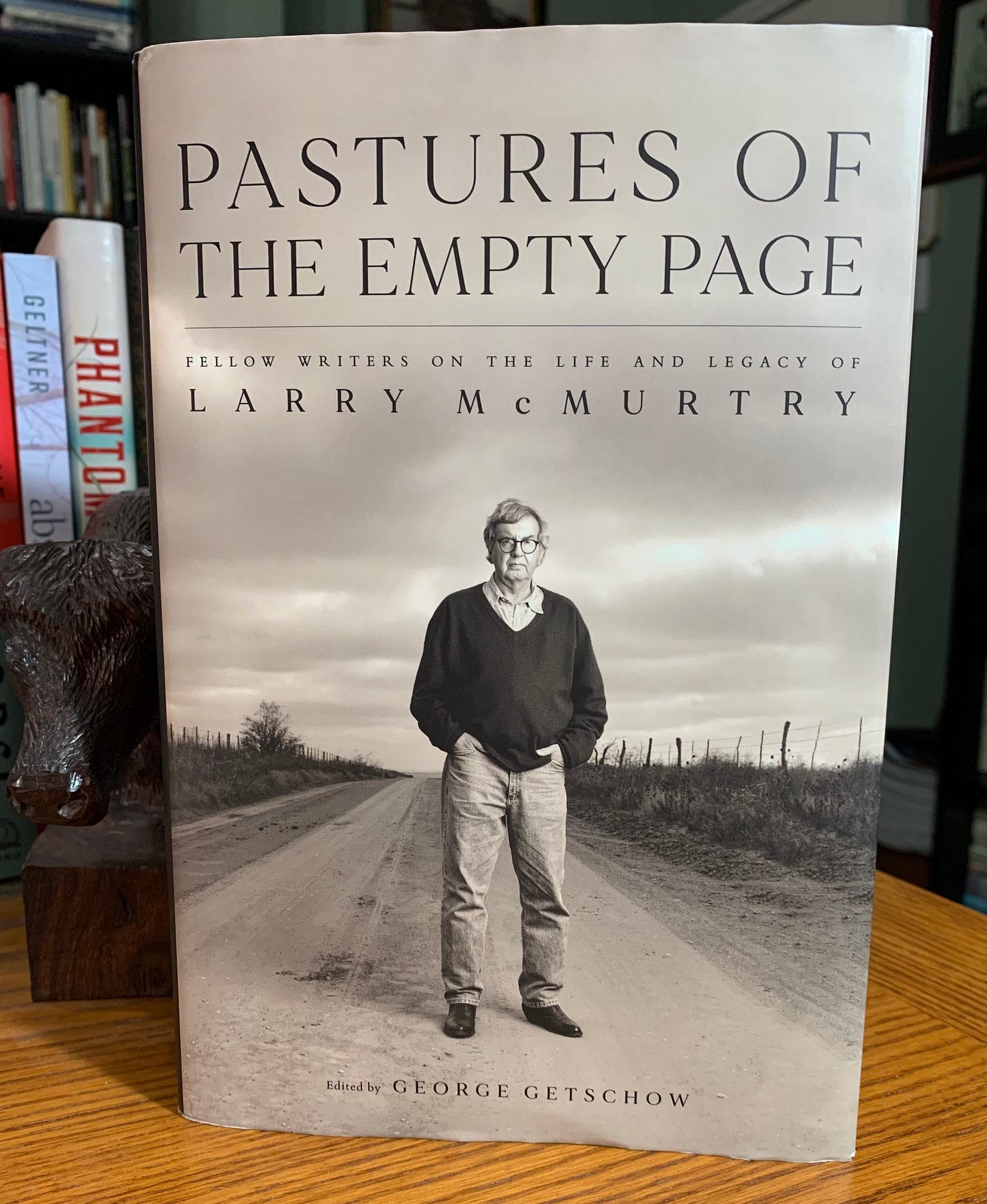

Larry Jeff McMurtry died on March 25, 2021. He was eighty-four-years-old. He was a Texan and cowboy. He was a novelist, essayist, and screenwriter—a literary legend. At his passing his family—James, his son, and Curtis, his grandson—held no funeral or memorial service. The only commemoration to celebrate this titan of Texas letters was a convocation of Texas writers organized by George Getschow, writer-in-residence at the Mayborn Literary Nonfiction Conference at the University of North Texas, and Kathy Floyd, administrator for the Archer City Writers Workshop. The gathering, playing off Larry’s tongue-in-cheek self-depreciating description of himself, was titled Larry McMurtry: Reflections on a Minor Regional Novelist. The group convened on October 9 in the year of McMurtry’s death in Archer City at the Royal Theater of The Last Picture Show fame. The convocation became the catalyst for a collection of essays edited by Getschow: Pastures of the Empty Page: Fellow Writers on the Life and Legacy of Larry McMurtry.

Like most books of collected essays written by disparate writers Pastures of the Empty Page is a mixed bag. Some notable submissions for me, however, are the three essays written by former students, turned friends, Dianna Ossana’s personal peek into Larry’s personal life, Stephen Harrigan and Lawrence Wright’s retrospectives, and Oscar Cásares’s wonderful “Snakes in a River.” What follows isn’t a review, rather it’s the essay I would have submitted if I had been asked.

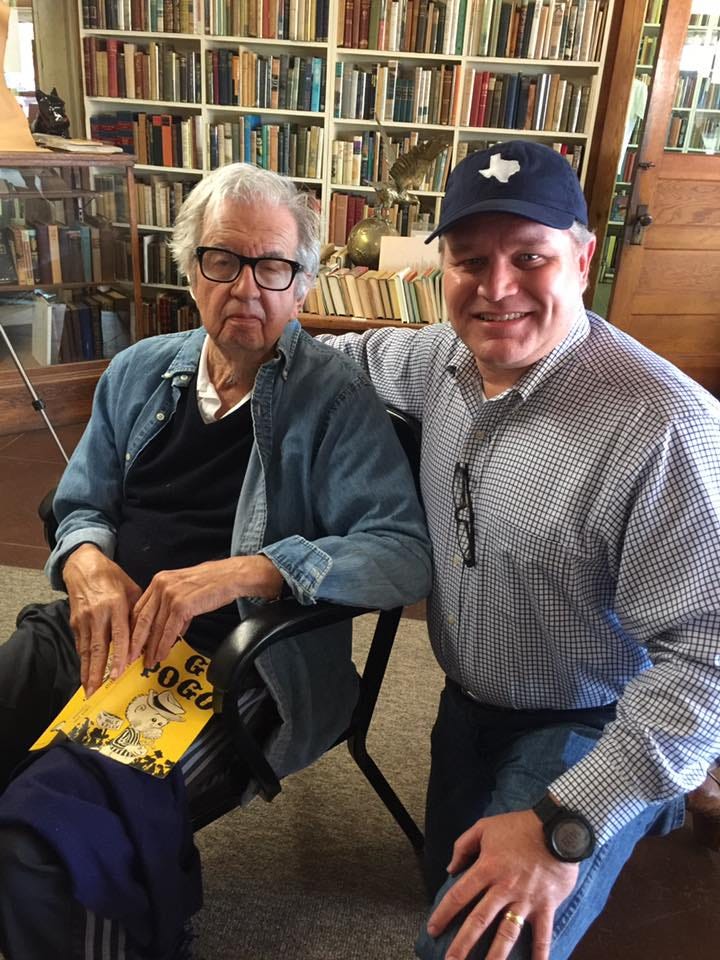

I met Larry McMurtry. Once. It was mid-March 2017 in his Archer City bookstore, Booked Up. He was reading a copy of Mort Walker’s I Go Pogo. My baby sister took a photo of Larry and me. I’m smiling, having met my literary hero. Larry sits expressionless, but with a weariness in his countenance—the showing signs of congestive heart failure and Parkinson’s disease. I had heard Larry occasionally visited the shop, to sit in the lobby and read a book or to work the stacks. We—that is my mother, two sisters, and niece—just happened to visit on one of those fortunate days.

Why my little sister and niece agreed to a day’s outing in Archer City was a bit of a surprise. Unlike my mother and older sister (and myself), neither is a book person. We lunched at Murn’s Cafe, walked through the Spur Hotel, and did some shopping (or the girls did). The real reason for making the drive, however, was to walk through the shelves of Booked Up. I recognized Larry the moment I stepped through the door. Everyone else just saw an elderly gentleman, with the exception of my mother. I’ve written about this before, but knowing I’d never do such a thing my little sister asked Larry for his autograph. She planned to give it to me as a present. “No,” he said. He never signed pieces of paper. He only autographed his books. Since I didn’t bring one, and all the ones in the store were already signed—and expensive, to boot—I didn’t procure his signature. To this day I take myself out to the woodshed for not bringing my beloved copy of Lonesome Dove. If I had, however, I’m sure he would have signed it with an expression of, He’s one of those, the bore. He probably would have much rather autographed one of his Berrybender books—a series he thought highly of. I’m convinced he would have been down right tickled to have signed my copy of Walter Benjamin at the Diary Queen—a favorite of his.

Though he didn’t agree to sign a scrap of paper, he did agree to the photograph. I asked him if he was currently working on anything. “No novels,” he told me. The Last Kind Words Saloon—his last novel (and by no stretch his best)—came out just three year before. He was working on screenplays. “That’s where the money is.” I knew of his ambivalence toward Lonesome Dove, what he called the “Gone With the Wind of the west.” It was, in his estimation, “a pretty good book . . . [but] not a towering masterpiece.” His ambivalence notwithstanding, I forged ahead and told him the television miniseries (based on the novel) had strengthened the bonds with my grandparents in their waning years. He graciously thanked me and I let him get back to his book.

Having met Larry isn’t the same as knowing Larry. I could tell you a lot about him, but, here again, knowing about him is not the same as knowing him. I didn’t know Larry McMurtry. I didn’t know what he thought about marriage and family, other than he had been married twice. Early in life he wed Jo Scott, which ended in divorce, but not before the birth of their son James, to whom he was devoted. Later in life he married Norma Faye Kesey, widow of fellow novelist Ken Kesey. I didn’t know his opinion on religion in general or Christianity in particular, other than in his bookless home, “There must have been a Bible, but I don’t remember ever seeing it.” And though his maternal grandfather was a Methodist preacher, Larry’s comment on the man in Paradise is less than honorable for a man who was to demonstrate Christlikeness. According to Larry, Oscar Sylvester McIver displayed a too familiar hypocrisy—a “vain, good-looking weak” man “prone to self-pity [and] self-flattery” who “bent a lot, particularly where the ladies of his congregation were concerned.” Diana Ossana, with whom Larry lived (platonically) and worked with for more than thirty years can claim to have known Larry McMurtry. In her wonderful entry to Pastures of the Empty Page, “Stirring the Memories,” she opens the door to the Tucson home she and Larry shared. She gives us a glimpse into his intimate world, particularly during his time of illness and depression.

What I knew was his work—or at least a good portion of his work. I’ve not read his whole oeuvre. Who could? He was the author of thirty-three novels, fourteen nonfiction books (memoir, travel, essay, and history), more than thirty screenplays, and hundreds of articles and book reviews. Outside his book of essays and three memoirs (each devoted to his three professional passions: novelist/essayist, bookseller, and screenwriter) readers ought to be circumspect about seeing too much of the storyteller’s life in the stories he tells.

Larry was born on June 3, 1936, in Archer City, Texas. The son of pioneers and cowboys, he grew up on a ranch east of there, off Texas Highway 25, in Windthorst, on a little rise called “Idiot Ridge.” The ranch is marked with the Stirrup brand—a rusted white-painted saddle stirrup nailed to the gate. That is where Larry first heard stories about cowboys and cowboying from those who lived it. He also dreamed of escaping what he saw as the small confines of ranch life. He would climb the windmill, sitting beneath its spinning blades, and watch cars and trucks weave their way to Dallas and Fort Worth and parts unknown—but always away from Idiot Ridge.

This much I know of Larry McMurtry: It was there, in the dust and heat of that northwestern Texas ranch that he learned the wisdom of hard work, of finishing a task, and of simple, plain language. He applied that wisdom to his own form of ranching: herding words into sentences, sentences in paragraphs, and paragraphs into books. Larry wrote five pages a day, every day (holidays included) without fail. Unlike his contemporary Cormac McCarthy, who published Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West the same year Larry published his Pulitzer-winning Lonesome Dove (1985), Larry didn’t get trapped in the brush or hang up his literary loop over this word or that, or whether a comma, semicolon, or em dash ought to be use here or there. Nor did he, à la McCarthy, use expansive language. “A writer’s prose should be congruent to the landscape he is peopling,” Larry said, and so, “I write plainly.” He worked efficiently and fast. He wrote The Last Picture Show in three weeks. The Last Kind Words Saloon took six. And of All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers, he said, “I just spewed it out, and never . . . looked back.” He was unsentimental about his work. When he was finished, he was finished and moved on. There were other more words to gather and brand. In 2016 there was a reunion of the cast and crew of the 1987 miniseries of Lonesome Dove. Larry had nothing to do with the production, the teleplay written by Larry’s friend Bill Whittliff. In regard to the reunion, I recall Larry writing on Facebook something to the effect, “I suppose some of you will be interested in this. I won’t be in attendance.” He had ridden on.

The wisdom of his work ethic wasn’t the only thing he learned all those years ago on Idiot Ridge. He also learned the wisdom of reading widely and well—promiscuously. The story is well told that Larry grew up in a bookless home, in a bookless town. That all changed when a cousin, bound for bootcamp and the horrors of World War II, stopped by Idiot Ridge and gave young Larry a box of books. It transformed his life. He became a bookman—a collector and seller of books. At one point Book Up housed a shelf busting 450,000 plus volumes. His own personal library, which filled his Archer City home, numbered in the near 30,000 volumes. As a reader he was as well versed in Don Quixote, Madame Bovary, and Anna Karenina (which he considered “the finest novel ever written”) as he was in The Gay Place, Charles Goodnight: Cowman and Plainsman, and I Go Pogo.

The greatest wisdom Larry learned from Idiot Ridge, however, situated as it is (and was) on the vast, windswept Texas plain between the middling town of Wichita Falls (some thirty minutes up the road) and the bustling metroplex of Dallas-Fort Worth (some two hours down the road) was the incalculable value of friendship. Perhaps it was because his father and uncles spent more time with cattle and horses than they did with fellow human beings or because as the bookish son of a rancher Larry never seemed to fit it, but for whatever reason Larry collected friends as assiduously as he collected books. And as with his books, his friends were not thrown away. Rather, they were cultivated and cared for—for a lifetime. Pastures of the Empty Page contain entries from three of Larry’s male friends: William Broyles, Gregory Curtis, and Mike Evans, who helped organize the stacks at Booked Up. All started out as students when he taught creative writing at Rice University in Houston. They remained amigos till the end.

But his greatest friendships—and the most legendary—were with women. They included actors like Diane Keaton and Cybil Shepherd, writers like Susan Sontag and Leslie Marmon Silko, and many you’ve never heard of. He was ever attentive and helpful to each of them and their extended families. He remembered their birthdays, sent flowers and chocolates on Valentines Day, and gifts of jewelry and books for Christmas. With each of these women he maintained lifelong (nonsexual) connections. He once told Maureen Orth, widow of NBC newsman Tim Russert, “If I thought a love affair would give me six months of intense pleasure but that this woman I had a real affinity for would not be in my life ten years from now, I would walk around the love affair. . . . I would go for the longterm friendship.”

Larry understood this ancient truth:“Friendship multiplies Joy and divides Grief.” Or, to put it in terms of a McMurtry-like character, cowboy artist Charles Russell, “Good friends make the roughest trail easy.” This was certainly true as Larry closed out his life. In a nod to his greatest character, Augustus “Gus” McCrae, who on his deathbed wrote letters to his lifelong sweetheart Clara Allen and to the one-time whore he rescued from Blue Duck, Lorena, so Larry wanted to speak to the ten women who had meant the most to him in his long, productive life before he died. Diana Ossana, who was with him in his last moments, dialed each and all expressed their love and admiration with a final adios.

I’ve learned much about writing from the sage of Idiot Ridge, but the greatest lesson he taught, put in the words of Henry Adams, is to “[walk] with one’s friends squarely up to the portal of life, and [bid] goodbye with a smile.”

Thank you for an article on 1 of my favourite authors. 🤠

Beautifully written. I had the pleasure of meeting McMurtry at Booked Up in the 90s. He had recently purchased the entire stock of a closing independent bookstore-in Fort Worth I believe. I found him in the large room just past the small warm room where you paid for your selections. It was a terribly cold day and the large room was poorly heated-if heated at all-and he was standing before a table, pencil in hand, taking out a book at a time which he inspected and priced with the pencil before placing it in a stack on the table. He wore cowboy boots, blue jeans, a nice wool coat and a scarf. I was shocked to see my hero standing before me. I didn’t know what to do or say. I was aware that he wasn’t especially thrilled with the adoration of his readers. Luckily, he paused a second and looked up from the book he was pricing to say, “Hello.” I think I replied, “Hello” and he returned his attention to what was truly important thing in the room--the books. I followed his example and went in search of a treasure to take home. By most people’s standards it wasn’t a very exciting event but for a bibliophile who valued McMurtry’s genius it was perfect-much like your essay.