The Mexican-American Chili War

What was most interesting to our hungry fellows . . . were their steaming pots of chile con carne.

S. Compton Smith

Wars either start in controversy or devolve into controversy. The Mexican-America War was one that began in controversy. Following the annexation of Texas in 1845 the United States inherited an ongoing dispute between the Republic of Texas and Mexico: the location of the border between the two countries. Was it the Rio Grande, as Texas claimed, or was it the Nueces River, as Mexico claimed? President James K. Polk attempted to resolve the dispute by offering Mexico a cash settlement of $25 million for the Rio Grande, if they would also throw in California. The Mexican government under President Antonio López de Santa Anna declined the offer. Polk then sent eighty U.S. soldiers into the contested territory, ignoring Mexican demands for them to withdraw north and east of the Nueces River. When the troops refused, Mexican forces attacked across the Rio Grande on April 25, 1846, repelling the Americans across the Nueces.

President Polk used this attack on American soldiers as the pretext to seek a declaration of war against Mexico from the United States Congress. He claimed American blood had been spilled on American soil by invading Mexican troops. Members of Congress were persuaded and on May 13, 1846, declared war on Mexico.

One wiry congressman, however, had serious doubts about the president’s assertion that Mexico had “shed the blood of our fellow citizens on our own soil,” and demanded the president answer eight “spot” questions concerning the exact location of this supposed bloodshed, as well as the legality of various claims to the disputed territory. The congressman was the Illinois freshman Whig Abraham Lincoln. In a separate speech, Lincoln said of Polk’s (mis)adventure into Mexico:

I more than suspect already, that he is deeply conscious of being in the wrong—that he feels the blood of this war, like the blood of Abel, is crying to Heaven against him. That originally having some strong motive . . . to involve the two countries in a war, and trusting to escape scrutiny, by fixing the public gaze upon the exceeding brightness of military glory—that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood—that serpent’s eye, that charms to destroy—he plunged into it.

Lincoln accused Polk of engaging in “the half insane mumbling of a fever-dream,” claiming “His mind, tasked beyond it’s power, [was] running hither and thither, like some tortured creature, on a burning surface, finding no position on which it can settle down, and be at ease.”

Whether any of that was true of President Polk or not, what is true is that the United States fought a two year war (1846–1848) with its southern neighbor Mexico, resulting in an estimated death toll of 38,000 persons, the settlement of the Texas-Mexico border, and the acquisition of some 525,000 square miles of the American southwest (including New Mexico and Arizona), California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

Men who would later become household names fought in the Mexican War: Zachary Taylor, Winfield Scott, Franklin Pierce, Robert E. Lee, and Ulysses S. Grant. All who fought and died in Mexico were known to families and campañeros. One of those men was S. Compton Smith. Little is known of him other than he was from New York and a surgeon assigned to General Taylor’s regiment. What is better known is the war memoir, in which he wrote:

The following incidents are all matters of fact, and will be readily recognized as such, by those of my readers, who were so fortunate as to have taken part in the exciting scenes of the campaign;—and although, in some instances, they are related in a colloquial style, to render them more attractive to the general reader, they are, nevertheless, truthful.

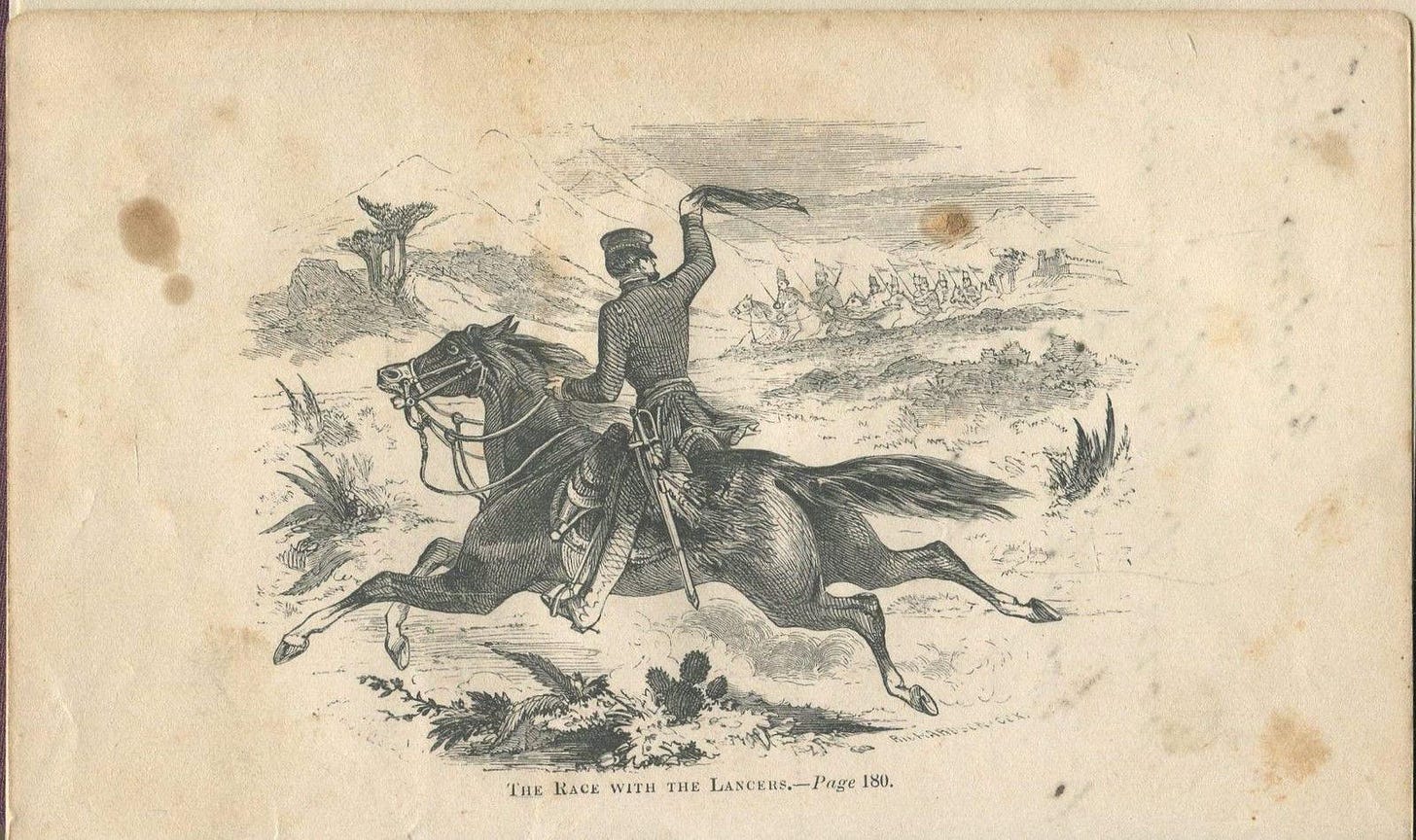

Two of those factual incidents involves chili con carne—a dish that became a favorite among the American soldiers in Mexico. The first occurred outside of Monterey, where Zachary Taylor’s troops were camped and allowed to purchase food and supplies from local merchants. The second occurred on patrol and involves the cowardice of Mexican lancers and the courage of Mexican women.

To this spot [the American camp outside of Monterey], also, would come the rancheros, who had learned that the Americanos del norte were not the cannibals their priests had at first taught them to believe; but were buenos Cristianos as well as themselves. Here would they assemble, and display their stock-in-trade, consisting usually of carne seco and carne fresco, leche de carbo, chile con carne [Footnote: A popular Mexican dish—literally red pepper and meat], tamales, frijoles, tortillas, pan de maiz, and other eatables, with puros, blankets, saddles, etc. These articles found ready purchases among our men, often at most unreasonable prices; for soldiers, as well as sailors, spend their money freely.

During the first day’s march, but a few incidents occurred, save an occasional exchange of shots, between our advanced vedettes and small reconnoitering parties of the enemy.

At Ramos,—one of our usual camping-grounds for the night,—we suddenly came upon one of those parties of Lancers, who, seated around their fires, were in the act of taking their suppers.

Our unexpected arrival somewhat interrupted their arrangements,—so much so, that they immediately took to the cover of the chaparral, without so much as untethering their horses, which, of course, fell into our hands.

But what was most interesting to our hungry fellows, of all the camp equipage they left behind, were their steaming pots of chile con carne, which, in their hurry to “vamos,” they had left upon the embers. Upon the ground were spread their serapes, as they had thrown themselves upon them before their fires. Even their carbines, lances, sabers, and pistols were scattered upon the ground, as they had carelessly thrown them from them, on their first arrival. They had also neglected to place a guard around the camp, and we had thus come upon them unawares.

As our men were greedily feasting upon their chile con carne, we were much amused by a sudden assault upon them, of a party of women, who, thoughtful of the flesh-pots, had desperately returned to the camp, and, in spite of all the efforts of the men to prevent them, rescued from a squad, who had gathered around the savory mess, each a vessel, and again disappeared in the chaparral.

Those Mexican troops seldom move without a crowd of women accompanying them.

The men, who were thus unceremoniously cheated out of their suppers, soon consoled themselves, with the fun we all derived from the incident; and in an hour or two all was forgotten, in the sound sleep that a hard day’s march brings to the weary soldier.

Abraham Lincoln, “‘Spot’ Resolutions, in the United States House of Representatives,” Washington, D.C., December 22, 1847, in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 1, ed. Roy P. Basler (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 420–2.

Abraham Lincoln, “Speech in the United States House of Representatives: The War with Mexico,” Washington, D.C., January 12, 1848, in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 1, 439–441.

S. Compton Smith, Chile Con Carne; or the Camp and the Field (New York: Miller & Curtis, 1857), vii, 99–100, 257–9, emphasis in original.

Y’allogy is an 1836 percent purebred, open-range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is created by a living, breathing Texan—for Texans and lovers of Texas—and is free of charge. I’d be grateful, however, if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber and/or purchasing my novel.

Be brave, live free, y’all.