The Ghost Dog

“Well, now, I’ll be dog-on’d, that’s the spookedest cuss that ever stole ham.”

John M. Priour

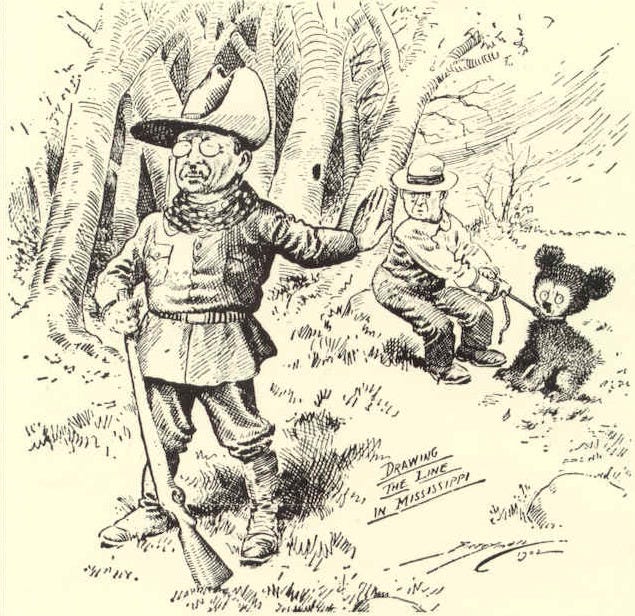

Before American elites like Theodore Roosevelt became fascinated with the exotic game animals of Africa, they were enamored with the exotic game animals of America: buffalo, pronghorn antelope, big horn sheep, mountain lions, and bears—black bears and grizzly bears. Roosevelt killed his first buffalo in 1883. And the Teddy Bear was created as a result of his refusal to shoot a treed and tied bear on a 1902 hunt in the Mississippi delta. The story reached political cartoonist Clifford Berryman. His drawing, depicting Roosevelt, gun in hand, with his back turned and his hand help up to an assistant holding a bear, above the caption, “Drawing the Line in Mississippi,” became famous.

The Washington Post published Berryman’s cartoon on November 16, 1902, where Brooklyn candy shop owner Morris Michtom saw it and got an idea. He and his wife also made stuffed animals for children and Michtom wanted to created a stuffed bear called, “Teddy’s Bear.” Securing Roosevelt’s permission to use his name, Michtom produced the bears and founded the Ideal Toy Company from the proceeds.

Another well-heeled blue blood from the East didn’t have a child’s toy named after him, but he did record his hunting exploits in the wilds of Texas—A Man from Corpus Christi, or the Adventures of Two Bird Hunters and a Dog in Texan Bogs (1894).

Bostonian Dr. Arthur C. Pierce traveled to Texas to hunt game birds. He hired John M. Priour to serve as his guide, who led the good doctor through four hundred miles of Texas bramble, bog, and bush—and mud holes aplenty. Accompanying Dr. Pierce and Mr. Priour was Priour’s beloved hunting dog, Absalom—the most useless hunting dog in Texas, then and now.

Like all good Texans, Mr. Priour entertained his guest with tall tales and plenty of joshing, which is simply built into a Texan’s DNA whenever around Yankees. One of the tales Mr. Priour told Dr. Pierce involved a ghost dog—or as the good doctor titled, “A Canine Spook.”

By the middle of the afternoon San Bernard Creek appeared, and driving a host distance out of the road we camped in the swampy bottoms. Although we had passed many cabins on our way, there were few of them near this stream. But if the settlers kept away from the creek, their dogs did not, and each inhabitant of the settlement was represented about our wagon by one of these animals. Long, yellow, lank and hairless, these four-footed denizens flocked about us as though a part of our own family, and, figuratively, Absalom took each of them by the hand and gave them a hearty welcome to the hospitality of our camp.

Like many people who had called upon us, these dogs could take no hint that they were not wanted, and in several instances the proverbial kick was attempted in order to keep them from overrunning us entirely. They were, however, familiar with such treatment and could dodge a stroke of they foot by a single motion of the body which would invariably leave the animal in the place and portion he was before.

Mr. Priour tried to punish one of the dogs which had his nose in our stew-pot. Several vigorous kicks were given in rapid succession. To me, standing a short distance away, it appeared as if the man’s foot went right through the body of the animal, but the dog did not remove his nose from the dish nor did my partner’s foot meet with any resistance. Whether the trained beast dropped flat upon the ground, allowing the intend blow to pass over him, or leaped high in the air above the danger, I could not tell, for the motion was too quick to follow with the eye.

“Well, now, I’ll be dog-on’d,” said the unsuccessful kicker, “that’s the spookedest cuss that ever stole ham. It wa’n’t never meant for him to be killed, and we couldn’t do it if we tried. Now, you year my words.”

“Why couldn’t we kill him? I don’t believe he could dodge a charge of shot.”

“Well, I wouldn’t kill that dog now for a million skunk skins.”

“Why not?”

“Why not? Why, I all you, he’s some spiritual descension, and what’s more, he didn’t dodge my foot either.”

“Yes, he did. You didn’t strike him.”

“I know I didn’t strike him.”

“Then he must have dodged you.”

“No, he didn’t dodge me.”

“What did he do then?”

“He just ghosted every time; now, I’ll be dog-on’d if I don’t know it, and I’m going to keep him along with us for good luck.”

“He dodged your foot, for I saw him slide under it.”

“No, you didn’t see him slide under it. I’m no elephant, I know, but when my foot starts, it generally gets there except in spooks. I tell you, that dog just all goes into spook when he wants to, and you might as well strike at your shadow with a club.”

“I don’t believe in spooks.”

“Well, what of that! I knew a man once that didn’t believe in bulls till he had a two-foot horn run through him, and was carried around on the bull’s head for a week, then he just begun to believe in bulls.”

“Were you ever tackled by a spook?”

“No, but I’ve know them to scare a man to death who might just as well been owned by a bull.”

“Well, did you ever see a spook?”

“Yes, I’ve seen a spook!”

“Where was it?”

“When I was living on the Aransas River.”

“What was the spook doing?”

“It cut around as though ’twas crazy; kept running and ramming into the fence, and brought up there kersmack every time. I thought once ’twas going to knock the boards all down.”

“What did it look like?”

“Looked like a big white goose.”

“Did anybody around there keep geese?”

“Yes, the man that lived near by had a whole pen full of them.”

“Wasn’t that a goose you saw?”

“No, ’twas a spook.”

“Why didn’t you run it down?”

“I did.”

“Did you catch it?”

“Of course I did. Did you ever know me to let a thing get when I once doubled down to get after it?”

“What did it look like after you’d caught it?”

“Looked like a goose just as it did before.”

“What did you do with it?”

“Picked the feathers off and had it for dinner next day. That’s what I did with it after I wrung its neck.”

“You stole a goose, that’s what your spook was.”

“No, ’twas a spook; but I tell you what, it looked and tasted so dog-on’d much like a goose that most anybody but me’ been deceived. But I took it for a spook when I first saw it, and I wa’n’t no such fool as to change my mind just because it had feathers; and besides there ain’t any law against sealing spooks.”

“I guess that was the same kind of a spook this dog’ll prove to be; one with something to it.”

“Well, don’t kill that dog anyway, he comes near enough a spook.”

This sealed the question on the champion dodger, and he was allowed—during his new friend’s presence—various privileges refused other and less active visitors.

We took a short stroll about the camp, and were lucky enough to shoot a few yellow squirrels which make a nice stew for our supper, which proved to be the best meal we had eaten for many days. Absalom got none of it nor did the other dogs, not even our new acquisition, now christened “Dodger.” We had by this time discovered that this latter reinforcement was built something like other Texan dogs—of skin and air principally. We had also discovered that a large and sweeping bush was a much better article for defending the camp than a club or foot, and we kept a dozen of the form weapons lying about camp, available for immediate use.

After a long evening our ten was spread upon the ground, and surrounded by a circle of canine guards, a dozen strong, we turned in for the night.