The Disappearing Frontier and the Cost of Freedom

A man can be free as a wolf, yet unable to do what he wants at all.

Alan Le May

Sitting in the Jorgensen’s bunkhouse, Ethan Edwards and Martin Pauly argued over their fruitless search for Debbie, Ethan’s niece and Martin’s “step-sister,” who had been captured by Comanches. Ethan was pushing on in the morning, leaving Martin behind to work the Jorgensen’s ranch. “I’m goin’ to keep on lookin’,” Martin says in John Ford’s 1956 film The Searchers. “How? You got any horses or money to buy ’em?” Ethan asked. “You ain’t even got money to buy cartridges.”

At this point in Alan Le May’s 1945 novel by the same title, the basis of Ford’s film, Martin comes to a sobering conclusion—a truth he can’t deny: “A man can be free as a wolf, yet unable to do what he wants at all.”

Martin’s realization could have served as the epigraph for Elmer Kelton’s 1978 comic novel The Good Old Boys—a story about the disappearance of the frontier and the cowboy way of life.

Kelton, of course, isn’t the first to cover these topics. With novels like Horseman, Pass By (1961) and to some extent Lonesome Dove (1985), as well as essays In a Narrow Grave (1968), Larry McMurtry became the Texas chronicler of the passing of the West and of the carefree cowboy. Nevertheless, Kelton’s The Time It Never Rained (1973) and The Good Old Boys are worthy lamentations of a time and country that was, is now no more, and will never be again.

The Good Old Boys is set in 1906, just as a new industrial revolution has introduced the “horseless carriage” (the automobile) to the now not-so-wild lands of West Texas. The loss of the once untamed frontier and the cavaliers who rode their ponies across it raises a question that sits at the heart of the novel: What cost are you willing to pay for personal freedom?

Though Kelton deals with this loss and this question with wit and humor in the character of Hewey Calloway, a fiddlefooted, good old boy who belongs to the vanishing past, readers are keen to Hewey’s increasing concern about how long he can hold on to the past—to the world of open ranges, cattle trailing, and fast horses. As the novel progresses the encroachment of the urban into the rural becomes palpable. It’s a world Hewey doesn’t and doesn’t want to understand. With wishful thinking, he poo-poos the automobile as a passing fancy. And yet, he knows the future belongs to his nephew Cotton, a mechanically minded and skilled young man.

But Hewey can’t divorce himself from the love of the open range. He fears the claustrophobia of farming. He loves the feel of horse reins and rawhide ropes and loathes the feel of wooden hoes and plows. He loves his brother Walter, a onetime freewheeling cowboy like himself, but can’t understand why Walter allowed himself to get caught in Eve’s rope, Walter’s wife, only to be tied to coveralls, crops, and cash commitments. Like all horsemen and cowmen, Hewey despises fenced off parcels and furrowed fields. His feelings are summed up by another onetime cowboy turned writer, J. Frank Dobie: “All ranch work was congenial to me as I grew up, even doctoring wormy calves by day and skinning dead ones by lantern light, but the year we boys tried raising a bale of cotton remains a dark blot.”

To Hewey, Walter and his boys work too hard scratching out a living in the dirt—to pay off the fat banker and his fat son-in-law who own the mortgage on their homestead. Their eyes are always cast down. His are on the horizon. The world he sees is framed by the ears of his cowpony, Biscuit, not by the rear end of a dumbwitted mule. In Hewey’s estimation, his view of the world is the best in the world. He would give a hardy “amen” to this George Sessions Perry sentiment:

To us Texans there is a quality of go and glamor about cowmen that farmers never attain. I don’t know what makes it. Is it the fact that they ride horses? That probably has something to do with it. But I am led for some reason to believe that it is the cowman’s mixture of pride and arrogance—plus his knowledge that he has casually put something over on the rest of us. For while the rancher goes through the violent motions of labor, he is actually having a wonderful time earning a living; doing something he would of spiritual necessity have had to do anyway for the good of his own soul, in order to live up to his own concepts of freedom and dignity. Perhaps that’s it, that the ranchers are the last free men in a swiftly industrializing America, and that they become thereby a noble and enviable symbol of what so many of the rest of us have eternally lost.

Eve, Hewey’s sister-in-law, would scoff, calling such romantic mawkishness foolishness. To her, and to some extent even to Walter, there’s something irresponsible in Hewey’s ambling life and carefree disregard for the claims others make upon his freedom. Eve fears Hewey will end up little more than a saddletramp, falling from his horse dead in some cow pasture or along some road as Boy Rasmussen does, whose death is the saddest and darkest note struck in Hewey’s prophetic rootless future.

The only pull to hanging up his chaps and donning a pair of overalls is Hewey’s love for Spring Renfro, the local schoolteacher. It’s impossible for Spring to live in the saddle as Hewey does—untethered and free as ash in the wind. But can Hewey live on the farm as Walter does—tied to a plow and saddled with a mortgage? Is Hewey willing to pay that price to have Spring? Can he, will he, give up his freedom for love or will he sacrifice love for his freedom? Hewey is like Martin’s wolf, free but unable to do what he wants—to have both. But he can’t. So, he must choose: hold onto the disappearing frontier for one last ride or embrace the future with a loving wife. The cost is high no matter the choice.

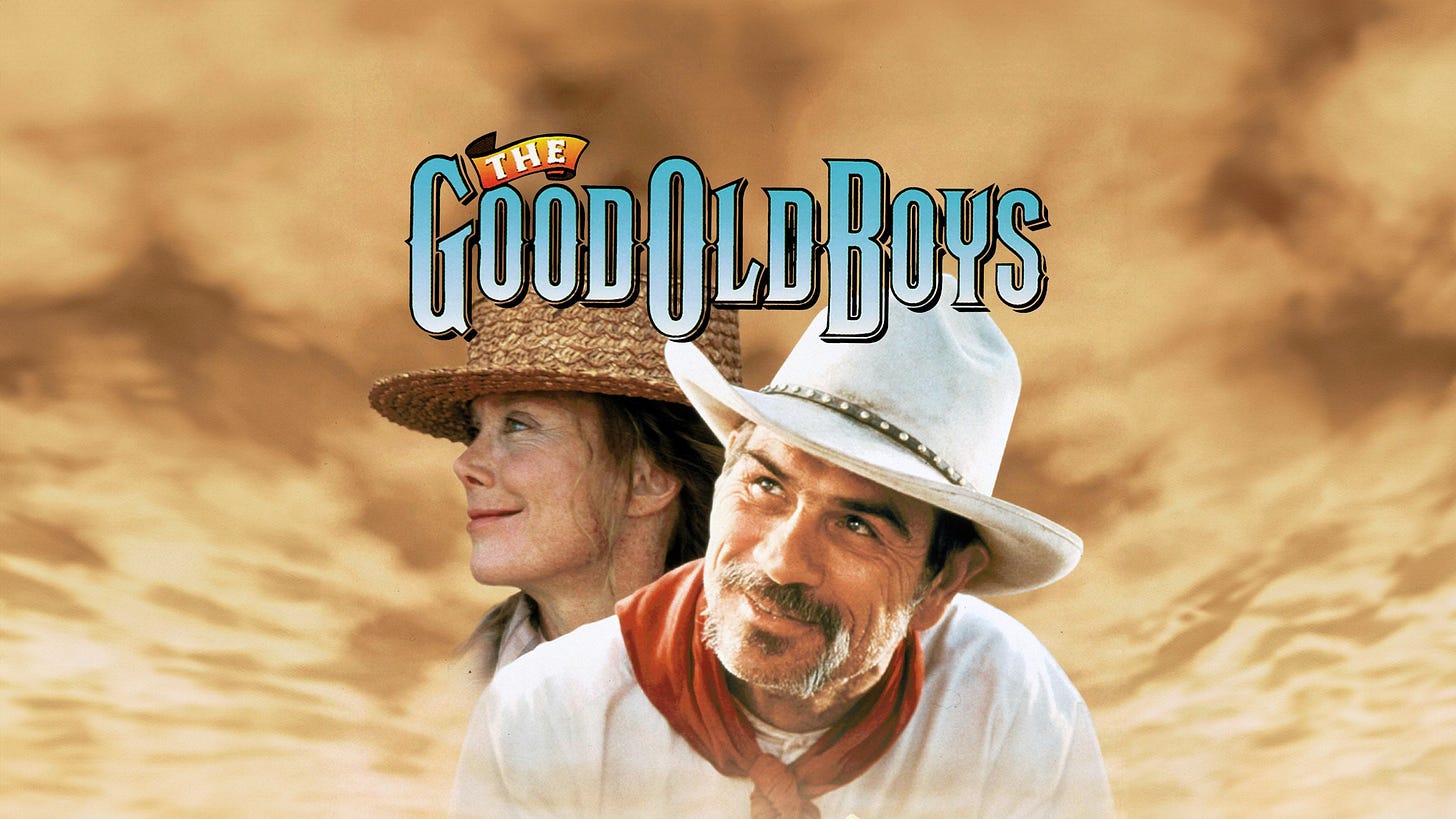

Tommy Lee Jones directed a faithful film adaptation of Kelton’s novel by the same title in 1995, starring Jones as Hewey, Terry Kinney as Walter, Frances McDormand as Eve, Sissy Spacek as Spring, and Matt Damon as Cotton.

J. Frank Dobie, Some Part of Myself (Boston: Little, Brown, 1967), 41.

Alan Le May, The Searchers, in The Western: Four Classic Novels of the 1940s & 50s (New York: The Library of America, 2020), 395.

George Sessions Perry, Texas, A World in Itself (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1942), 73.

Y’allogy is an 1836 percent purebred, open-range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is created by a living, breathing Texan—for Texans and lovers of Texas—and is free of charge. I’d be grateful, however, if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber and/or purchasing my novel.

Be brave, live free, y’all.

Great write-up here Derrick. - Jim