The Death of Days Gone By

“She patted his hand. Gnarled, ropescarred, speckled from the sun and the years of it. The ropy veins that bound them to his heart. There was map enough for men to read. There God’s plenty of signs and wonders to make a landscape. To make a world.”

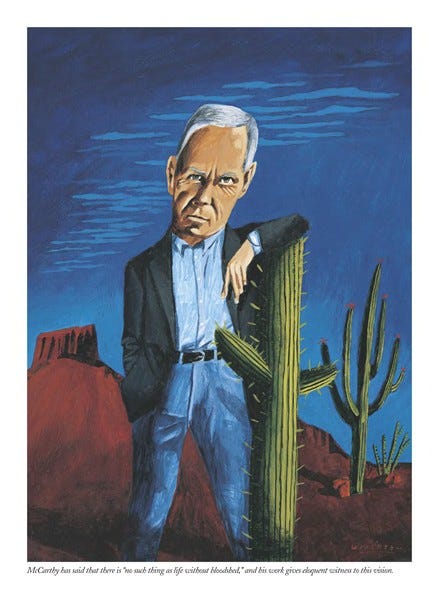

Cormac McCarthy, Epilogue, The Border Trilogy

Once left, home is never the same; not because the location is not the same upon your return, but because you, others, or the times are not the same before your leaving.

This is a central theme in Cormac McCarthy’s trilogy of novels placed along the Mexican-American border. The three novels that make up The Border Trilogy all concern themselves with love and loss, heroes and villains, family and friends, old traditions and new inventions. The trilogy, in many ways, is an epic tale befitting the Greek heroes of ancient days. The heroes—John Grady Cole and Billy Parham—are flawed characters but exhibit flawless cowboying skills. Each goes in quests for something lost—sometimes metaphysical, such as a way of life or a purpose in life; sometimes physical, such as horses, or a brother, or a lover. Each has an Achilles’ heel—John Grady’s is his heart, Billy’s is his brother.

All the Pretty Horses

The trilogy opens with the most famous of the three novels, All the Pretty Horses. Set in South Texas in 1948, sixteen year old John Grady Cole rides into Mexico with his best friend Lacey Rawlins, after everything and everyone John Grady knew was either taken away or deserted him. On their ride south, the boys stumble upon Jimmy Blevins, a young boy with a mysterious past, riding a mysterious horse—one John Grady and Lacey believe stolen.

After John Grady and Lacey are separated from Blevins in a nighttime fracas, the two teenagers come across the vaqueros of the Hacienda de Nuestra Senora de la Purisima Conception, the ranch owned by Don Hector Rocha y Villareal. Both boys prove themselves capable hands, but John Grady possesses an uncanny skill with breaking wild horses and soon finds himself the trusted confident to Don Hector—at least when it comes to horses, not when it comes to his beautiful daughter Alejandra.

John Grady soon falls in love with Alejandra, and she with him. But their love is doomed to fail, especially after John Grady and Lacey are implicated as an associate of Blevins, who is accused of a triple murder. John Grady and Lacey are arrested and sent to prison. Blevins is murdered by the local police. Lacey is released from prison after begging stabled by the leader of a prison gang. And after his own knife fight, John Grady is mysteriously released.

He tried to rekindle his relationship with Alejandra, but she refused. John Grady then decides to steal Blevins’s horse and return it to Texas, in hopes of find its rightful owner. When John Grady returns home he finds that his father and the nurse who took care of him as a child have died.

In typical lyrical fashion, McCarthy’s prose is engaging and challenging. And in All the Pretty Horses the cadence of his writing often sounds like the hoof beat of galloping horses.

The Crossing

The most challenging of the three novels is the second installment: The Crossing. Concerning three different round-trip crossings from New Mexico to Old Mexico, the novel opens with sixteen year old Billy Parham in the years just before World War II. In each of the crossings, Billy is looking for something, but returns home without the object of his quest. In fact, with each crossing, he loses more than the article of his attention—he loses a part of himself. The Crossing is clearly the most mystical of the three novels, as is Billy and his quests across the border.

The first crossing occurs after Billy captures a pregnant she-wolf and ties her muzzle shut. Instead of killing the animal, he determines to release her in the Mexican mountains, or original home. Mysteriously and inexplicable Billy rides off without a farewell to his father or mother, or his fourteen years old brother Boyd. Once in Mexico, Billy is forced to defend the wolf from packs of dogs and men who want the wolf for their own sport or gain. Refusing to sell the wolf, she is finally confiscated by local officials. Placed in a circus as a sideshow curiosity, Billy tracks the wolf to a barn where she is engaged in a dog fight. Billy decides to shoot the wolf. And then he trades his rifle for her dead body. He returns her to the mountains and buries her.

For Billy, the wolf became a mysterious, almost spiritual creature—a thing to bring meaning to his life. On his return to New Mexico, Billy encounters a former priest turned hermit who challenges his ideals of life. When Billy makes it home he discovers his parents have been murdered, presumably by two Mexican Indians, his dog’s throat cut (though still alive), and his father’s six horses stolen. Boyd is boarding at a neighbor’s home.

The second crossing, with Boyd in tow, is an attempt to recover their father’s horses. After much searching—and after rescuing a young and beautiful girl from rape—they discover some of the horses are in the possession of a one-armed man. The Parham brothers have two altercations with the man. The second altercation results in the one-armed man falling from his horse, breaking his back, and later dying. Cowboying their horses out of Mexico, Billy and Boyd are overtaken by the one-armed man’s compatriots. Boyd is shot. Billy is only able to save Boyd’s life by enlisting the help of local farmers, who nurse the boy back to health in their village.

The farmers and villagers make up mythical tales about Boyd, and when he’s strong enough he and his sweetheart disappear into the mountains, leaving Billy as ignominiously as Billy left Boyd at the first crossing. Billy searches for his brother, but to no avail. He returns to America just after December 7, 1941. Billy’s three attempts to enlist in the Army are unsuccessful due to a heart defect.

For the next few years, Billy bounces around the southwest, working on various ranches as a cowhand. Determined to find Boyd, Billy makes his third crossing into Mexico. Once there, he hears about the revolutionary exploits of a young gringo and his lover. Eventually, Billy understands the stories are about Boyd, who had died years before. Finding Boyd’s bones, Billy decides to return them to New Mexico.

On the return trip, Billy is waylaid by bandits who desecrate Boyd’s bones and stab Billy’s horse. The horse doesn’t die, and with the help of kindly men the horse recovers from his wound. Billy recrossed the Rio Grande back to New Mexico where he buries Boyd’s bones, just as he buried the she-wolf after his first crossing.

The novel ends with a nuclear test in the New Mexican desert and Billy weeping after chasing away an old dog. Simpler times, when men rode horses and “the godmade sun” shone in the sky, had ended. The world had become a new and strange place.

Cities of the Plain

The trilogy ends with the apply titled Cities of the Plain. Taken from the book of Genesis and the destruction rained down on Sodom and Gomorrah, Cities of the Plain opens after World War II, in the aftermath of the atomic bomb, on the federally condemned Cross Fours Ranch of Mac McGovern in Alamogordo, New Mexico. The novel brings together John Grady Cole, now twenty, and Billy Parham, now twenty-eight. Some of Billy’s mystery is revealed and is portrayed more realistically, while John Grady grows more mysterious.

Leading with his heart more than his head, John Grady falls in love with another beautiful Mexican girl. This time an epileptic whore, Magdalena. Her beauty and isolation is what first attacks his attention, but her condition is what makes him fall in love with her. As he does throughout the novel, John Grady must rescue those in need—Magdalena, a near unbreakable horse, and the runt from a litter of puppies.

Billy leads with his heart too. But his heart is not set on women, it is set on John Grady. The younger man reminds him of his brother Boyd—the one he couldn’t save. But in Cities of the Plain, Billy is determined to save John Grady, if from nothing else at least from himself.

The tension in the novel comes in fact that Magdalena’s pimp, Eduardo, is also in love with her. John Grady convinces Billy to drive to Mexico and speak with Eduardo, to try and buy Magdalena. When that fails, John Grady tries to convince a blind pianist, whom he calls the maestro, to become the girls padrino or godfather. The maestro refuses and warns John Grady that Eduardo will kill the girl before he let her leave.

Undaunted, John Grady bribes a cabdriver, Ramon, to pick Magdalena up on a certain day at a certain cafe. Magdalena agrees to escape the whorehouse where she works and rendezvous with Ramon at the cafe. But something goes wrong. Ramon doesn’t meet her, another man does—he says he’s Ramon’s cousin. The cabdriver promises to take her across the border where John Grady is waiting for her, but instead he drives her to the river where one of Eduardo’s henchmen is waiting for her.

When Magdalena doesn’t show, John Grady crosses the border and finds her in the morgue. He confronts Eduardo and the two pull knives. Eduardo is the more expert, slashing John Grady many times, carving a deep “E” into his thigh, and opening his gut. John Grady is only able to kill Eduardo through blind rage and by drawing his nemeses in close.

Bleeding profusely, John Grady is helped by a boy into a clubhouse. Billy shows up later, but is unable to save his friend—his brother. And as he did with Boyd, Billy carries the body of John Grady back to New Mexico.

The Epilogue

The trilogy ends fifty years later. Billy is now seventy-eight—a vagabond. Under an overpass in Arizona, Billy encounters a mysterious man who tells him of a dream, and a dream within the dream, of a traveler in the Mexican mountains sacrificed by pagans. Billy struggles to understand the meaning of the dream, but finally gives up and moves on. The epilogue ends with Billy, having been taken in by a kindly woman, suddenly awakens out of a dream about Boyd. The woman comes to check on him. He tells her that he doesn’t understand who he is or the purpose of his life. She assures him that she understand, and tells him to sleep. “I’ll see you in the morning.”

The epilogue offers a sense of redemption for Billy. He wasn’t able to save the wolf or Boyd or John Grady. He wasn’t able to save the way of life he’d grown to love. Time had passed him by and he no longer had a place in the world. His was the death of days gone by. All that had happened before was but now a dream. But the woman, she was real and alive, and as long as Billy lived he had a place in the world—a place to belong and others to love. He had a home.