That Woman Will Fight

General, if you’re going on to the Nacogdoches Road, you can have my oxen, but if you go the other to Harrisburg, you can’t have them, for I want them myself.

Pamelia Mann

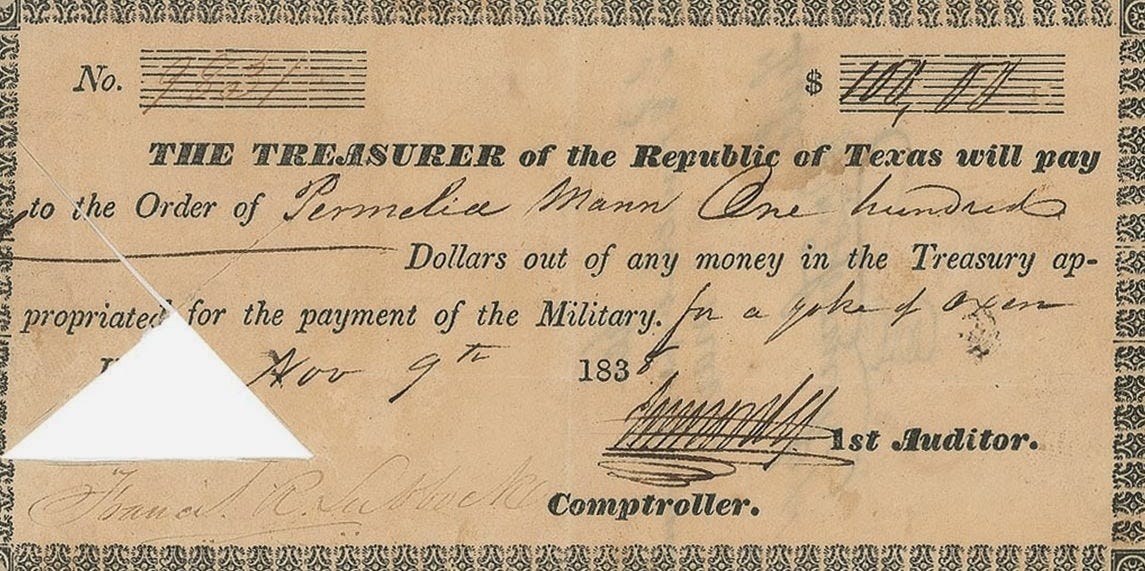

Pamelia Dickinson Mann, like most Texas women, was not one to tangle with—especially when she got her tail up. She ran a popular inn at Washington-on-the-Brazos. But when General Antonio López de Santa Anna and his Mexican Army crushed the defenders at the Alamo—and the delegates at Washington skedaddled—she and her two sons (and presumably her husband Marshall Mann, though he doesn’t factor into this story) fled in the Runaway Scrape. She managed to get away with two large freight wagons, laden with personal effects, pulled by two four-team oxen, along with an additional yoke of oxen.

Early spring had been exceedingly wet, turning the roads into a slushy, slick bog. And though the fine folks in Cincinnati, Ohio provided two cannons to aid the cause of Texas Independence, moving them was near impossible without the muscle of either oxen or mules—neither of which General Sam Houston had. When the “Twin Sisters,” as they were dubbed, arrived at Groce’s Plantation Houston met with Mrs. Mann and persuaded her the use of one of her teams to pull the cannons over the muddy roads. She had one caveat: they were not to be taken to Harrisburg. She said to Houston, “General, if you are going on to the Nacogdoches Road, you can have my oxen, but if you go the other to Harrisburg, you can’t have them, for I want them myself.”

Mrs. Mann intended to reach Nacogdoches, where the road lay open to the safety of the United States. Harrisburg was hemmed in with creeks and swamps, perfect for trapping an army, which Houston did at San Jacinto, not for fleeing an army—and that was what Mrs. Mann was doing.

Houston assured her he had every intention of taking the Nacogdoches Road. What he didn’t tell her was how far down that road he planned to travel. About six miles from Groce’s the road forked—one leading on to Nacogdoches, the other leading to Harrisburg. Houston took the Harrisburg fork. About ten or twelve miles down that road Mrs. Mann caught up with the Texas Army. As Private Bob Hunter put it, who witness the scene, “Mrs. Mann over took us out on the big prairie hog wallow and full of water . . . a very hot day.” She was hot, too—mad enough to eat the devil, horns and all.

“General, you told me a damn lie. You said that [you] was going on the Nacogdoches Road. Sir, I want my oxen.”

Houston tried to reason with her. “Well, Mrs. Mann, we can’t spare them. We can’t get our cannon along without them.”

He might as well have thrown kerosene on a live fire. “I don’t care a damn for your cannon. I want my oxen.”

Recounting this encounter years later, Private Hunter wrote, “She had a pair of holster pistols on her saddle pummel and a vary large knife on her saddle. She turned around to the oxen and jumped down [from her horse] with the knife and cut the rawhide tug that the chin was tied with.” She remounted “with whip in hand and away she went in a lope with her oxen.” “Nobody said a word,” Hunter noted, not even Houston.

After Mrs. Mann rode away, the wagon master, Captain Conrad Rohrer, protested to Houston: “General, we can’t get along without them oxen. The cannon is done dogged down.” Houston said they would have to do the best they could to drag the cannons themselves. But Rohrer wouldn’t hear of it. He said, “Well, General, I will go and bring them oxen back.” He wheeled his horse and set his spurs in pursuit of Mrs. Mann and her oxen, with one of his teamsters trailing behind. As he rode off, Houston stood in his stirrups and hollered, “Captain Rohrer, that woman will fight.”

“Damn her fighting,” Rohrer shouted back.

With nothing else to do to get the Twin Sister unstuck, Houston dismounted and said, “Come on boys. Let’s get this cannon out of the mud.” According to Hunter, “The mud was very near [Houston’s] boot tops” as he put his shoulder to the wheel of the limber. Eight or ten others joined in and forced the cannons from the muddy road. Men were pressed into service to pull them throughout the afternoon until they reached the oak and pine woods around Matthew Burnett’s homestead, about six miles down the road, where the Army made camp for the night.

About nine or ten o’clock that evening Captain Rohrer and his teamster arrived in camp mud splattered, wet, and hungry—and empty-handed. He announced that Mrs. Mann refused to return the oxen. Some of the men noticed the Captain’s shirt was cut up in several placed. “How come your shirt tore,” they asked. He explained that Mrs. Mann had asked for strips of his shirt to use as baby rags. None of the soldiers believed him. They knew what happened. He demanded the return of the oxen and she took her knife to him, cutting pieces off of his shirt.

According to Private James Winters, “The boys had a good joke on the wagon master, and they did not forget to use it.”

I’m sure they didn’t.

After the Revelation, with Texas an independent nation, Mrs. Mann opened one of the first hotels in the city of Houston—the Mansion House. In 1839, however, a curious thing happened to her: she was found guilty of forging the name of William Barret Travis on legal documents. It was a strange verdict, not only because Travis had been dead for three years by that time but also because she couldn’t write. She received an excessive penalty: death. However, Sam Houston’s law firm, along with a delegation of Houstonians and The Morning Star newspaper, persuaded President Mirabeau Lamar to grant her a full pardon. She died a year later of yellow fever, on November 4, 1840, a free woman, leaving an estate valued at $40,000, including the Mansion House and other real estate holdings, to her two sons.