Texas Tales: Up the Chisholm Trail

I was used to the comforts of home, with plenty of good milk, butter and eggs, chicken, fruits and vegetables, and at night I had a nice soft feather bed to sleep on. –John Taylor Allen

Y’allogy is 1836 percent pure bred, open range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is free of charge, but I’d be much obliged if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber. (Annual subscribers of $50 receive, upon request, a special gift: an autographed copy of my literary western, Blood Touching Blood.)

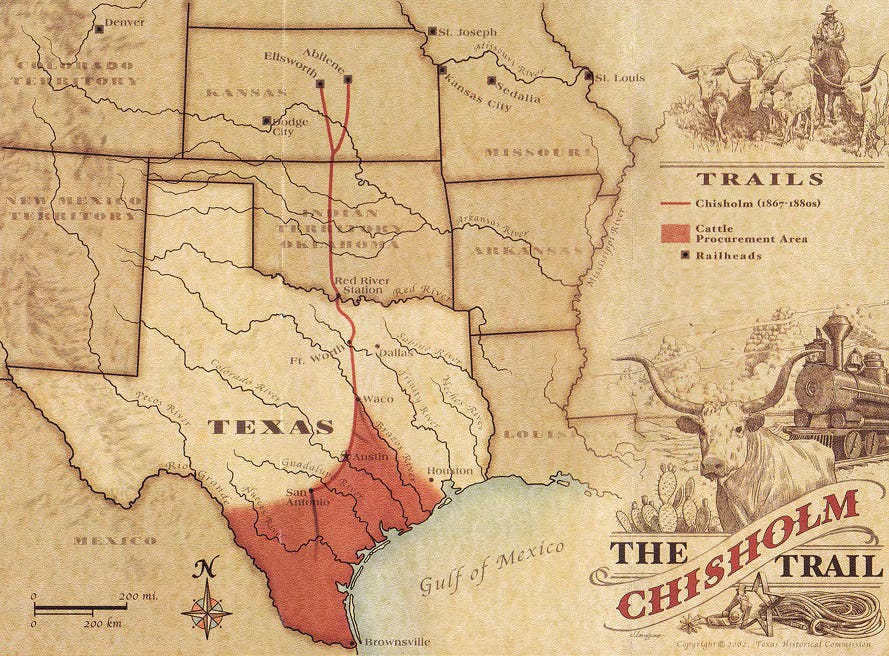

By the time the great Texas cattle trails ended in the mid- to late-1880s, estimates of anywhere from six to ten million longhorns were brought to Colorado and Kansas railheads or pushed into Wyoming and Montana. This included the famed Chisholm Trail.

The first herd of 2,400 steers up the Chisholm Trail, in 1867, belonged to O. W. Wheeler and his business partners. They intended to winter their cattle on the plains, then push them onto California. At the North Canadian River in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) the Wheeler cowboys stumbled on Scot-Cherokee Jesse Chisholm’s wagon tracks, who in 1864 began hauling goods to Indian camps about 220 miles south of his post near modern Wichita, Kansas. This trail was well-known in the Territory and was usually referred to as the Trail, the Kansas Trail, the Abilene Trail, or McCoy’s Trail. When Wheeler’s cowboys discovered this beaten down road they decided to forego California and follow the Trail to Abilene, Kansas.

In time, the Trail, which only applied to the tracks north of the Red River, came to be known as the Chisholm Trail. The earliest references to the Chisholm Trail in print were from the May 27 and October 11, 1870, editions of the Kansas Daily Commonwealth and the April 28, 1874, edition of the Denison Daily News, which referred to it as “the famous Chisholm Trail.”

Texas cowboys soon applied the name to the entire trail from the Rio Grande to Central Kansas. It didn’t take long for the Chisholm Trail to become the preferred nomenclature of cattle gathered in South Texas and punched up the old Shawnee Trail, through San Antonio, Austin, and Waco, before breaking off to Fort Worth, then east of Decatur on to the Red River Station, where herds crossed into Indian Territory. Once in Kansas, cattle could be delivered to railheads in Abilene, Ellsworth, Junction City, Newton, Wichita, or Caldwell.

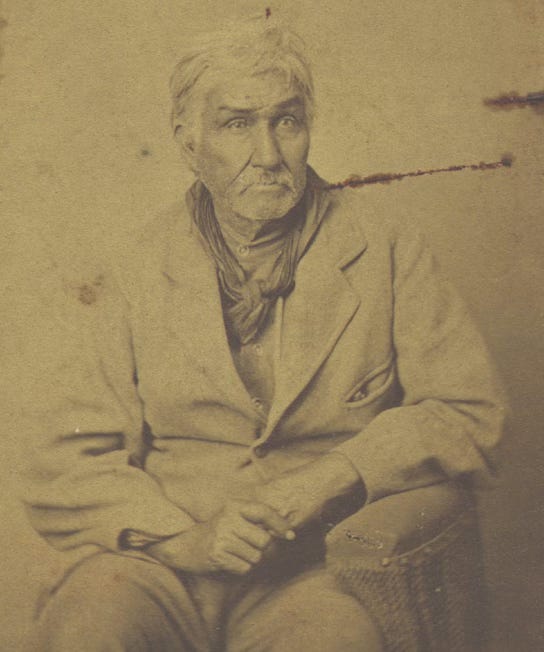

One cowboy, of the estimated 25,000 punchers, who drove cattle up the Chisholm Trail was John Taylor Allen. The following is his first-hand account of driving cattle up the Chisholm Trail, in which he recounts how he got the nickname “Parson,” how bad the chow was, what happened to his brother during a stampede, and how he almost drowned in a river.

Ever since I learned to ride a horse I was trained to work with herds and care for horses and cattle on my father’s homestead near Honey Grove in Fannin County. Even before I could ride, I herded a large flock of sheep. In those days, wolves were so bad it required the utmost vigilance to keep the sheep from being killed and eaten. Sheep were necessary to us then, and profitable. From their wool we carded, spun and wove our clothing and we depended on mutton for our meat. Many a woman made a suit of clothes for her husband and sons from the wool of their own sheep.

As I grew older, I had to herd cattle and horses. On the prairie the luxuriant grasses grew in such abundance that it was profitable to raise cattle. There were no railroads then and to market our stock we would drive them to Kansas.

For several months we would not be under a roof. We slept out in the open, exposed to the weather, through storms and rains, thunder and lightning, and often had to deal with stampeding cattle.

The first trip up the trail I took I shall never forget. I was used to the comforts of home, with plenty of good milk, butter and eggs, chicken, fruits and vegetables, and at night I had a nice soft feather bed to sleep on. But, oh, my! What a change when I started up the Chisholm Trail to Kansas. How I longed for my comfortable home.

It required all my courage and determination to keep me on the way. The brackish water, the coarse cornbread, the fried fatback, the badly made coffee, were no substitutes for the food at home. For the first few days of the drive I almost starved. The cowboys and the cook called me the parson.

They would taunt me because I would not eat their crude food. “Parson,” they said, “you will come to your appetite in time.” And I did. Often after a long hard day, I would arrive in camp, exhausted after chasing cattle in a stampede, with lightning and thunder and rain or sleet beating in my face, and sit down to a meal of corn-pone and fatback, washing it down with bad coffee.

How it lingers in the memory. I would come in tired and ready to eat only to find that other cowboys came in before me and left nothing. The would say, “Wait, Parson, and I’ll start a fire and soon have some bread and coffee.”

Another scene comes to mind in vivid detail. The night was so dark and the storm so menacing that we could not see beyond the length of our arms, except in the brief flashes of lightning. We were feeling our way along, not knowing what we might run into. The frightened cattle were rushing ahead of us, invisible except when lightning pierced the darkness. We had to press on, for fear the cattle would be lost. For three days and nights we had been in the saddle nearly all the time. How we longed for a good sound sleep.

During this stampede my brother’s horse stepped into a deep hole and its feet stuck, throwing the horse and my brother Loss somersaulted over the horse’s head. The horse turned over on my brother as he fell, seriously hurting him. I stopped to help him but he said, “No, go catch my horse.” After falling, the horse got up and ran after the stampeding cattle.

With the steady use of the quirt and spurs I succeeded in reaching the herd and finally found that horse and brought him back to my brother, who was badly crippled by the fall. With some difficulty I got him into the saddle and back to camp, where our wagon and mess tent were. For several days he had to ride in the wagon before he was able to mount his horse again. This accident, I believe, shortened his life, for he never fully recovered from the injury he sustained.

It was hard sometimes to get the herd across a stream, but after we would get one started it would usually result in the rest following without trouble. It was on one of these occasions when I almost lost my life.

We had to swim the rivers on horseback and we usually constructed a raft on which to float across our wagon. The Big Walnut Creek, in the Osage Nation near the Kansas line, was rapidly flowing. We were anxious to cross before night. On the opposite bank was a log raft tied to a tree. I told my brother Loss that I was going to swim across for that raft we could ford our wagon and gun across.

I took hold of the rope with my teeth, after tying two 30-foot variates together, and started to swim across. I got along first-rate until I reached the middle of the stream. The weight of the rope in the water began to tire me and I was pulled under. I was not frightened and kept my presence of mind. My brother yelled for me to let go of the rope, but I was determined to carry out my plan. I would hold my breath when I went under so I would not strangle.

I only had a short distance to go when my strength gave out. I made one strong effort and was just about ready to give in when I found my feet could just touch bottom. I made one more effort and after two or three strokes I got hold of the limb of a bush hanging on the edge of the bank. It saved me from going under.

I was so worn out that I just lay there, half-drowned, holding on to the branch until I gathered enough strength to crawl up on the shore. I did not take long to get the raft over and ferry our traps and grub across, but it sure seemed an age when I was swimming across that dangerous stream. I have often thought that if that river had been a yard wider, I would have reached that other shore, that undiscovered country from which no traveler ever returns.

John was born a few years after Texas statehood, on October 29, 1848, in a log cabin on his father’s homestead six miles northwest of Honey Grove in Fannin County. He married Mary Emma “Mollie” Finch in 1878. They had seven children together. John died in 1927, at the age of seventy-nine, and was buried in the Allens Chapel Cemetery. Mollie died two years later.

John Taylor Allen, “Up the Chisholm Trail,” in 100 Tales of Old Texas, ed. Murphy Givens (Corpus Christi: Nueces Press, 2020), 275–8.

Support Y’allogy—

Much obliged, y’all.

Thanks for sharing this interesting article.

When I read accounts like this I’m often struck by just how well they’re written, especially remarkable given that the writers would have had very little in the way of a formal education.

Thanks. I am 7th generation native Texan. When I was a child I asked my granny what we were; pertaining to a discussion in elementary school about family ethnicity and nations of origin. Granny looked down at me and replied, "We are just Texans." That statement was the foundation of an admiration and pride in my homeland. Hat tip to you amigo.