Texas Tales: The Scalping of Josiah Wilbarger

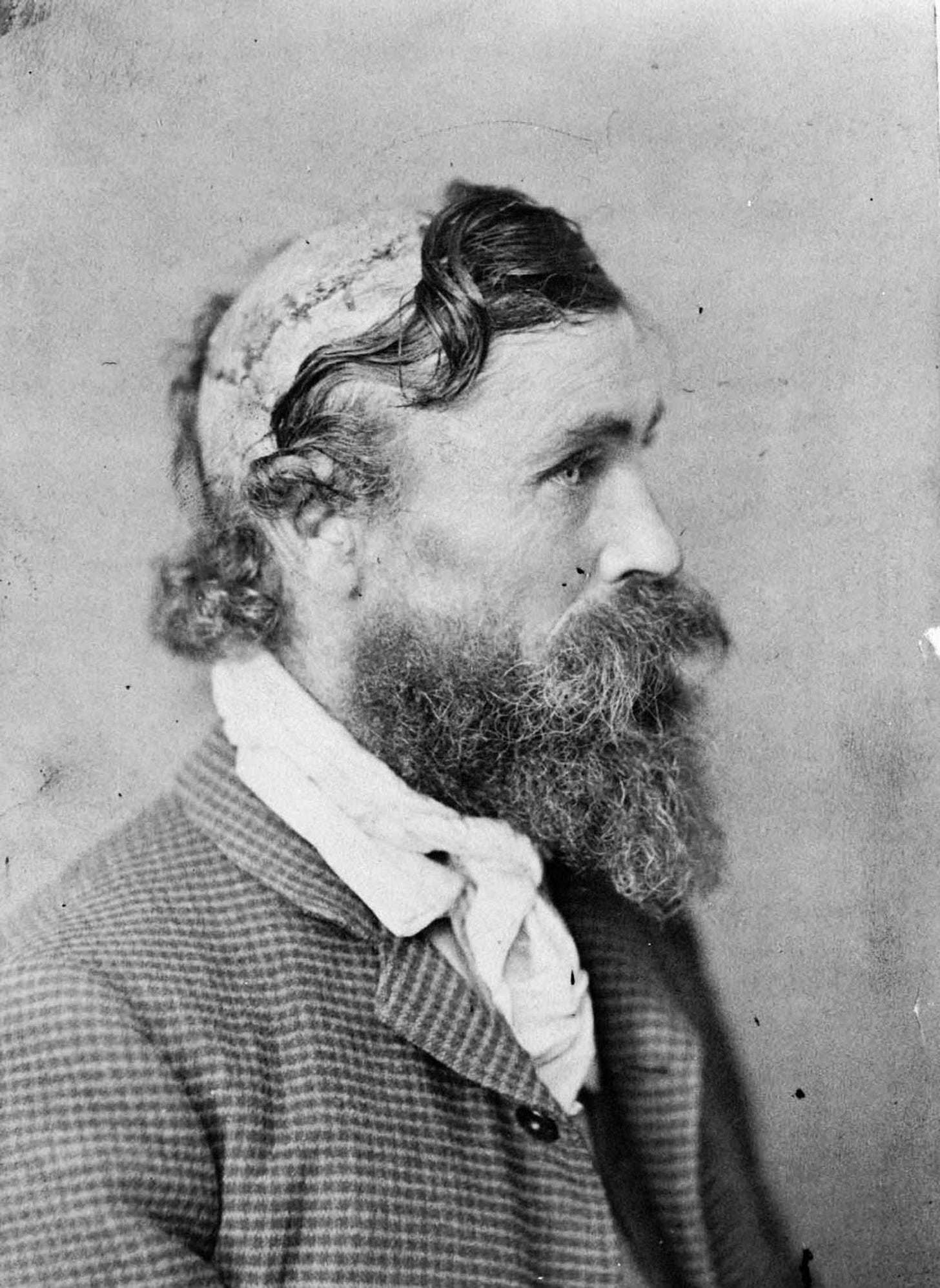

An Announcement and a Warning. First the warning. The following article relates the true story of a scalping, a savage custom that was not uncommon on the Texas frontier. Included is a photograph of a scalped victim. Why tell this story? Two reasons. When I began Y’allogy I determined to present Texas in all her glory and gore—to not shy away from the good, the bad, and the ugly. This leads to the second reason: the announcement.

Coming December 1, 2024: Blood Touching Blood—my first novel. A literary western set in far West Texas in 1880 against the backdrop of the Apache Wars, Blood Touching Blood explores how violence leads to retaliatory violence in like manner, if not in greater degrading degrees. Scalping as a barbaric and dehumanizing practice is a central feature in my story, just as it is in the story of Josiah Wilbarger.

When his scalp was torn from his skull it created no pain from which he could flinch, but sounded like a distant thunder.

John Wesley Wilbarger

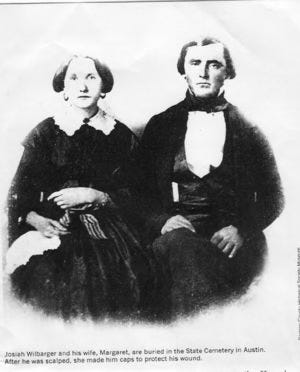

Josiah Pugh Wilbarger was an early Anglo settler of Texas, finding himself in Matagorda County in 1828. By March of 1830, he had settled his family along the Colorado River as part of Stephen F. Austin’s colony. He selected a tract of land about ten miles north of present-day Bastrop, on what is called Wilbarger Creek. His nearest neighbor, Reuben Hornsby, settled his family on the eastern bank of the Colorado River, roughly nine miles south of present-day Austin. Both families were beyond the edge of the frontier, living in a land dominated by the dominate band of natives: Comanches.

Early August 1833: Wilbarger and other men by the names of Christian, Strother, Standifer, and Haynie met at Hornsby’s cabin. Standifer and Haynie, recently removed from Missouri, came to Texas to look the land over. Wilbarger, Christian, and Strother agreed to show them the country.

What happened next was a harrowing tale of death and depredation. The tale is told by Wilbarger’s brother, John Wesley Wilbarger.

[. . .]

[They] rode out in a northwest direction to look at the country. When riding up Walnut creek, some five or six miles northwest of where the city of Austin stands, they discovered an Indian. He was hailed, but refused to parley with them, and made off in the direction of the mountains covered with cedar to the west of them. They gave chase and pursued him until he escaped to cover in the mountains near the head of Walnut creek. . . .

Returning from the chase, they stopped to noon and refresh themselves, about one-half a mile up the branch above Pecan spring, and four miles east of where Austin afterwards was established, in sight of the road now leading from Austin to Manor. Wilbarger, Christian and Strother unsaddled and hoppled [hobbled] their horses, but Haynie and Standdifer [sic] left their horses saddled and staked them to graze. While the men were eating they were suddenly fired on by Indians. The trees near them were not large and offered poor cover. Each man sprang to a tree and promptly returned the fire of the savages, who had stolen up afoot under cover of the brush and timber, having left their horses out of sight. Wilbarger’s party had fired a couple of rounds when a ball struck Christian, breaking his thigh bone. Strother had already been mortally wounded. Wilbarger sprang to the side of Christian and set him up against his tree. Christian’s gun was loaded but not primed. A ball from an Indian had bursted Christian’s powder horn. Wilbarger primed his gun and then jumped again behind his own tree. At this time Wilbarger had an arrow through the calf of his leg and had received a flesh wound in the hip. Scarcely had Wilbarger regained the cover of the small tree, from which he fought, until his other leg was pierced with an arrow. Until this time Haynie and Standifer had helped sustain the fight, but when they saw Strother mortally wounded and Christian disabled, they made for their horses, which were yet saddled, and mounted them. Wilbarger finding himself deserted, hailed the fugitives and asked to be permitted to mount behind one of them if they would not stop and help fight. He ran to over take them, wounded, as he was, for some little distance, when he was struck from behind by a ball which penetrated about the center of his neck and came out on the lift side of his chin. He fell apparently dead, but though unable to move or speak, did not lose consciousness. He knew when the Indians came around him—when they stripped him naked and tore the scalp from his head. He says that though paralyzed and unable to move, he knew what was being done, and that when his scalp was torn from his skull it created no pain from which he could flinch, but sounded like a distant thunder. The Indians cut the throats of Strother and Christian, but the character of Wilbarger’s wound, no doubt, made them believe his neck was broken, and that he was surely dead. This saved his life.

When Wilbarger recovered consciousness the evening was far advanced. He had lost much blood, and the blood was still slowly ebbing from his wounds. He was alone in the wilderness, desperately wounded, naked and still bleeding. Consumed by an intolerable thirst, he dragged himself to a pool of water and lay down in it for an hour, when he became so chilled and numb that with difficulty he crawled out to dry land. Being warmed by the sun and exhausted by loss of blood, he fell into a profound sleep. When awakened, the blood had ceased to flow from the wound in his neck, but he was again consumed with thirst and hunger.

After going back to the pool and drinking, he crawled over the grass and devoured such snails as he could find, which appeased his hunger. The green flies had blown his wounds while he slept, and the maggots were at work, which pained and gave him fresh alarm. As night approached he determined to go as far as he could toward Reuben Hornsby’s, about six miles distant. He had gone about six hundred yards when he sank to the ground exhausted, under a large post oak tree, and well nigh despairing of life. Those who have ever spent a summer in Austin know that in that climate the nights in summer are always cool, and before daybreak some covering is needed for comfort. Wilbarger, naked, wounded and feeble, suffered after midnight intensely from cold. No sound fell on his ear but the hooting of owls and the bark of the coyote wolf, while above him the bright silent stars seemed to mock his agony. . . .

[Here the author relates a strange story of Wilbarger seeing the spirit of his sister Margaret Clifton, who, unbeknownst to him, died the day before in Missouri. She said to him: “Brother Josiah, you are too weak to go by yourself. Remain here, and friends will come to take care of you before the setting of the sun.” She then moved in the direction of the Hornsby cabin and disappeared.]

Haynie and Standifer, on reaching Hornsby’s had reported the death of their three companions, stating that they saw Wilbarger fall and about fifty Indians around him, and knew that he was dead. . . .

[Here the author relates another strange story. This time a dream by Mrs. Hornsby, who woke her husband saying, “I know that Wilbarger is not dead.” She told Mr. Hornsby that she had seen Wilbarger naked, wounded, and scalped, but alive. She was insistent on the matter and wouldn’t let her husband sleep. Before daybreak, she had cooked breakfast and sent the men off in the predawn light.]

The relief party . . . approached the tree under which Wilbarger had passed the night. . . . [He] was sitting at the root of the tree. He presented a ghastly sight, for his body was almost red with blood. . . . [Mistaking] him for an Indian, [they] said: “Here they are, boys.” Then Wilbarger rose up and spoke saying: “Don’t shoot, it is Wilbarger.” When the relief party started Mrs. Hornsby gave her husband three sheets, two of them were left over the bodies of Christian and Strother until the next day, when the men returned and buried them, and one was wrapped around Wilbarger, who was placed on [a] horse. Hornsby being lighter than the rest mounted behind Wilbarger, and with his arms around him, sustained him in the saddle. . . .

When Wilbarger was found the only particle of his clothing left by the savages was one sock. He had torn that from his foot, which was much swollen from an arrow wound in his leg, and had placed it on his naked skull from which the scalp had been taken. He was tenderly nursed at Hornsby’s for some days. His scalp wound was dressed with bear’s oil, and when recovered sufficiently to move, he was placed in a sled . . . because he could not endure the motion of a wagon, and was thus conveyed several miles down the river to his own cabin.

Josiah’s wounds to his leg, hip, and neck healed. The place where his scalp was taken, however, never fully recovered. His brother John wrote, “The scalp never grew entirely over the bone. A small spot in the middle of the wound remained bare, over which he always wore a covering. The bone became diseased and exfoliated, finally exposing the brain. His death was hastened, as Doctor Anderson, his physician, thought, by accidentally striking his head against the upper portion of a low door frame of his gin [grain] house many years after he was scalped.” Josiah lived twelve additional years, dying on April 11, 1845. He was forty-four-years old.

Source:

J. W. Wilbarger, Indian Depredations in Texas (Austin: Hutchings Printing House, 1889; n.p.: The Pemberton Press, 1967), 8–12.

Josiah Wilbarger’s story is also told in Biographical Encyclopedia of Texas with minor variations.

Y’allogy: Texan Spoken Here.

To support Y’allogy please click the “Like” button, share articles, leave a comment, and pass on a good word to family and friends. The best support, however, is to become a paying subscriber.

I'm a descendant of Margaret Clifton, and this story has long been a part of our family lore. I was startled and thrilled to find such a complete and compelling narrative in the words of a contemporary of Josiah's. Thank you for posting it.

For those further interested: in Bartholomew District Park, at the corner of 51st Street and Berkman Drive in northeast-ish Austin, there is a plaque commemorating this event. There is also a "Wilbarger House" in Bastrop, complete with an historical marker.

Great story. Looking forward to your book.