Texas Tales: The Lynching of "Moss Top"

The one who had the machete had a mop of frizzy hair that looked like a buffalo’s mop. . . . Right away one of the boys whom we called Chubby Cody, named him Moss Top.

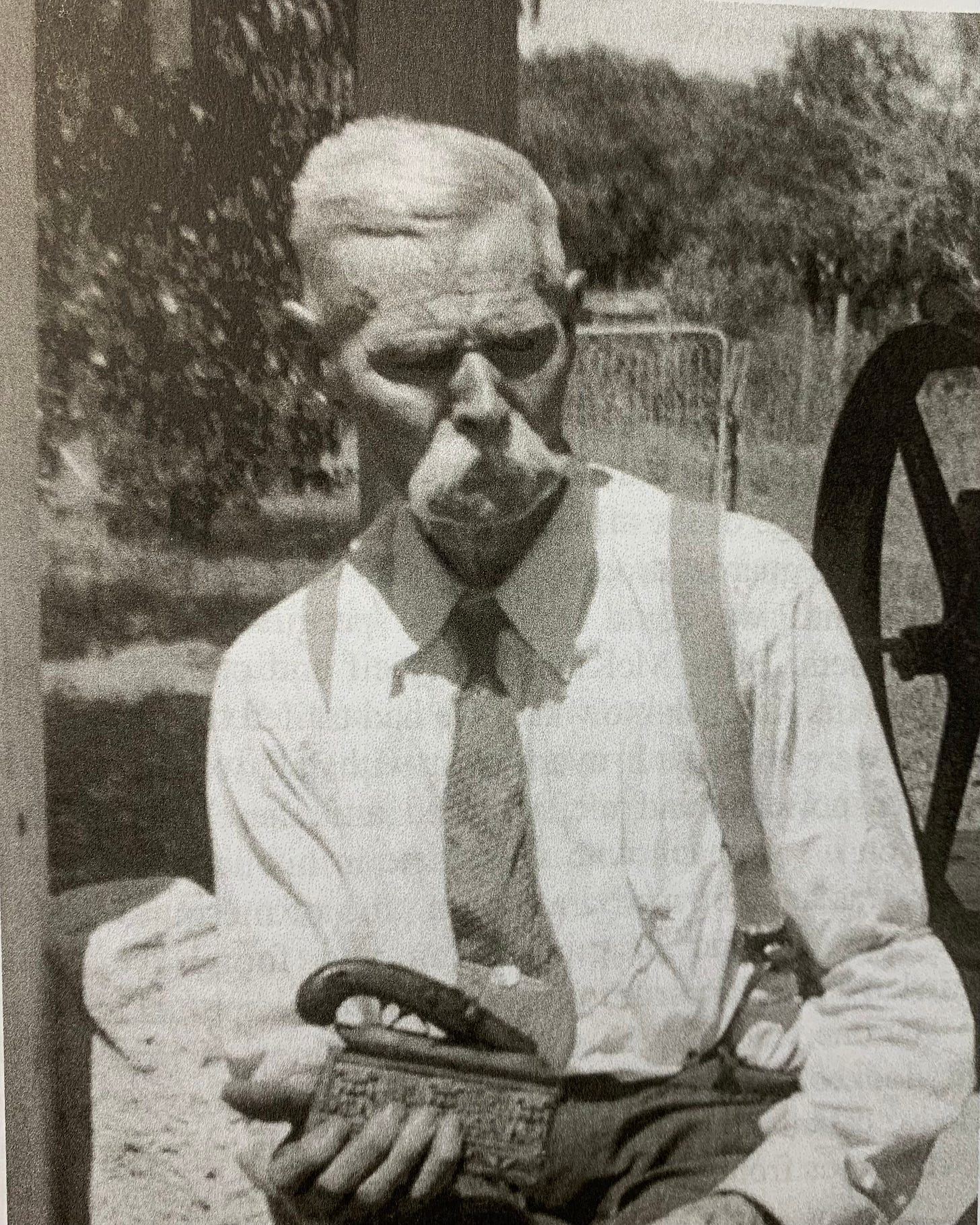

John B. Dunn

Old-time Texas Rangers were a rough bunch. As typical Texans, each one fit this description, at least in the popular mind: “A large-sized Jabberwock, a hairy kind of gorilla, who is supposed to ride on a horse. He is a half alligator, half human, who eats raw buffalo, and sleeps out on the prairie. He is expected to carry four or five revolvers at his belt.”

The hyperbole notwithstanding, some of the rangers who rode the range of the Texas frontier did have a notorious reputation as being just this side of the law than the outlaws they hunted. In a few cases it was near impossible to slide a slip of paper between the activities of those who wore a badge and those who didn’t. In the movie Tom Horn, starring Steve McQueen, Horn, who’s been hired by members of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association and backed by the U.S. Marshal’s office to put an end to rustling by any means necessary, asks Marshal Joe Belle, “What’s the difference between a U.S. Marshal and an assassin?” Belle answers: “A marshal’s check comes in on time.”

The blurring of legal lines on the frontier was a known fact, and one smudged on occasion by individual Texas Rangers who took upon themselves the offices of judge, jury, and executioner. One such individual and episode occurred in the summer of 1874 when ranger John B. Dunn and a group of others lynched a Mexican man accused of taking a machete to a fellow ranger.

Born in Corpus Christi on January 18, 1851, “Red” John, as he was called to distinguish him from his cousin who was also named John Dunn, joined the Texas Rangers at the age of nineteen, under Captain Bland Chamberlain. “Red” John became something of a local legend. One historian described him as “a vigilante, a Texas Ranger, and at times a scoundrel who was quick at the draw and as ornery as a riled up javelina in the Brush Country.”

Besides the tale told here, he also took part in tracking down Mexican raiders in what became known as the Nuecestown Raid, rescuing a number of Anglo men who had been taken captive. His exploits were published in his Perilous Trails of Texas (1932), including this one.

A word of warning: His references to Mexicans and blacks are tinged with racial overtones that were typical of that time and place among white Texans.

The Shooting of Mark Judd—One day three or four of us left camp to go to town, that is, the village of Concepción which was about two miles from where we were stationed. On our way in we met two of our boys riding on their way back to camp. One of them was riding a race horse that belonged to Lieutenant [Lark] Ferguson. The rider, who was pretty full of booze began wallowing around on his horse and talking very loud. His actions excited the horse, and as the other horses began moving, he thought it was a race that was coming off and wheeled and ran in the opposite direction, as fast as he could go. We knew it would only make matters worse if we tried to catch him, as this would only make him ride faster and he had the fastest horse in the company.

In a few moments both he and the horse disappeared into the chaparral and we rode on in the direction of Concepción. When we got in sight of the captain’s quarters, we saw the horse going there in a dead run, with the rider, Mark Judd, hanging over on the horses shoulder. Both Judd and the horse were covered with blood.

When the horse halted at the door of the captain’s quarters, we eased Judd down and saw that he had been shot in the eye with a small caliber pistol, and that one side of his face was laid open with a machete. (Mexican knife.) He was unconscious and could say nothing.

We got on the trail of the blood and followed it to a Mexican jacal (house) where even the door was splattered with blood. We found no men within, but only women and children who denied any knowledge of the affair.

The Fight at the “Jacal”—We threw guards around this “jacal” and several others in the vicinity until more of the boys came so that we could search the premises thoroughly. Dave Odem, Billie McIntosh, myself and one other man guarded the first “jacal” to which we had trailed the blood.

We were in a vacant garden or path overgrown with tall weeds, when I heard a noise behind me. I turned around and there lying on his stomach with a machete in his hand, was a Mexican. About ten feet from this one was another Mexican grasping a club of mesquite wood.

We captured and disarmed them and found that they had crawled about thirty yards toward us before we spotted them.

The one who had the machete had a mop of frizzy hair that looked like a buffalo’s mop than anything else. Right away one of the boys whom we called Chubby Cody, named him Moss Top. The latter was in his shirt sleeves and his body was covered with awful sores from which the stench was terrible.

We lost no time in getting to camp with our prisoners. When we arrived there, a scout under Steve Burleson came in and asked us what we had with us. We told him the circumstances and he thereupon threw a noose around Moss Top’s neck and began throwing the other end of the rope over a tree. Just then Captain [Warren W.] Wallace and some more of the boys came running up. At first the captain tried to bluff the boys out of hanging the prisoner, but when that did not work, he gave his word of honor as a gentleman that if they would desist, he would keep him under guard until the Grand Jury was in session and would turn him over to the law.

The Captain Breaks His Word and Its Consequences—A few days later we learned that Moss Top had been liberated. The boys put spies on his track and found that at a certain time every evening he took a rope and machete and went after wood to the creek.

The next day, two of the boys hid in a gully that ran into the creek and caught him easily. They made him mount behind one of them and tied his legs underneath the horse’s belly so that if he happened to fall or jump, he could not escape.

They struck a run for a small lake in the mesquite brush which was surrounded by mesquite timber, but they could not find a tree large enough or high enough to swing him clear of the ground. After losing considerable time trying to find one, they sighted a tree that forked high enough from the ground to fasten his head in the forks and leave his toes about four inches from the ground. They then jammed his head into the fork of the tree, took the end the rope and put it around his neck and one of the forks of the tree. They tied the other end of the rope around the horn of the saddle and made the horse pull until the man’s neck was broken. After this they removed the rope that they had used and tied him with his own rope.

He was not found for several days and it was in the month ofAugust; the weather was very warm and showery. Consequently the body was a terrible sight, swollen beyond recognition and emitting a terrible odor.

The Mexicans pretended that they were afraid to take him down and the Rangers refused to do so, so they sent to Santa Gertrudis (King’s Ranch) for a detail of negro soldiers who came and buried him.

Mark Judd, the man who [Moss Top] had shot and stabbed, recovered, but he was blind in one eye and carried a scar from his hair down the side of his neck.

In later life, “Red” John settled in Corpus Christi as a dairyman and married Lelia Nias, who died on November 12, 1920. He kept a private museum of war relics he began collecting at seventeen in his Shell (UpRiver) Road home. He died on November 3, 1940, and is buried in Rose Hill Cemetery next to his wife.

Ruth Dodson, “The Noakes Raid,” Frontier Times, vol. 23, no. 10 (July 1946), 175–87.

J. B. (Red) John Dunn, Perilous Trails of Texas, ed. Lilith Lorraine (Dallas: Southwest Press, 1932), 81–84, original spelling and grammar retained.

Manuel Flores, “Texana Reads: J. B. “Red” Dunn: Vigilante, Texas Ranger, scoundrel, gentleman,” Caller Times, August 7, 2020.

Alexander Sweet and John Armoy Knox, “That Typical Texan,” Sketches from Texas Siftings, reprint (1882; Corpus Christi: Copano Bay Press, 2018),104.

Y’allogy is an 1836 percent purebred, open-range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is created by a living, breathing Texan—for Texans and lovers of Texas—and is free of charge. I’d be grateful, however, if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber and/or purchasing my novel.

Be brave, live free, y’all.