Texas Camel Corps

The camel has his virtues—but they do not lie upon the surface. . . . Irreproachable as a beast of burden, he is open to many objections as a steed.

Amelia Blanford Edwards

It had to be a joke, right? What was the horse and mule dominated cavalry of the United States Army doing messing around with camels? The producer of the 1976 film Hawmps! took it as a joke, placing Slim Pickens, Denver Pyle, and Jack Elam on the humped backs of those hairy beasts as cavalrymen. But it was no joke. In 1836 Major George H. Crossman, who fought in the Indian War in Florida under future president General Zachary Taylor, tried to persuade the War Department to adopt camels as transport animals. His proposal no doubt produced a few chuckles. But Crossman was serious. So was the War Department. It rejected his scheme.

Others, however, saw nothing to laugh about in Crossman’s proposal. To them it was perfectly logical—especially among those who had lived in the Middle East and witnessed the versatility and utility of camels. One such man was George R. Glidden who lived twenty-eight years in the Levant. In 1852 he presented a copy of his memoir to the Senate Committee on Military Affairs. He argued that camels were superior to mules as beasts of burden in arid regions. Mules, he said, would only drink salty or brackish water when pushed to extremes, and even then they might not drink. Camels, on the other hand, though they could endure six or seven days without water, would drink the poorest water as if it flowed from the purest stream. They could eat virtually anything: thistle, prickly pear, and other thorny vegetation. Camels could carry, on average, four hundred pounds. Particularly strong animals could carry 450 to six hundred pounds—and easily make thirty miles a day under that weight. Saddled, carrying two hundred pounds or less, they could travel eight to ten hour a day and make fifty miles.

Another man familiar with the harsh environment of the Middle East and the adaptability of camels was U.S. diplomat George Perkins Marsh. In 1856 he sent a copy of his book The Camel to the War Department in an effort to convince the army to use them as supply animals.* His book received a welcomed patron in Secretary of War Jefferson Davis.

A graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, Davis, who had served under General Taylor in northern Mexico during the Mexican War, met Crossman in Mexico in 1846. The two men discussed the value of camels as a military asset, particularly in the arid regions of the southwest where forts could not be supported by native agriculture, making the movement of supplies over long, dry distances vital. As Secretary of War, Davis tried to mitigate the southwestern water problem by ordering wells dug at intervals where natural watering sources were more than forty miles apart. In the Trans-Pecos of Texas, where surface water is as scarce as hen’s teeth, that proved to be a lot of wells. Though water was struck in some places, it was seldom in sufficient quantities to water troop stock and troopers. So when Marsh’s book arrived at the War Department, Davis didn’t see the joke in utilizing camels as transport animals. In fact, a year before Marsh mailed his book, Davis had succeeded in persuading Congress to allocate $30,000 for “the purchase and importation of camels and dromedaries to be employed for military purposes.”

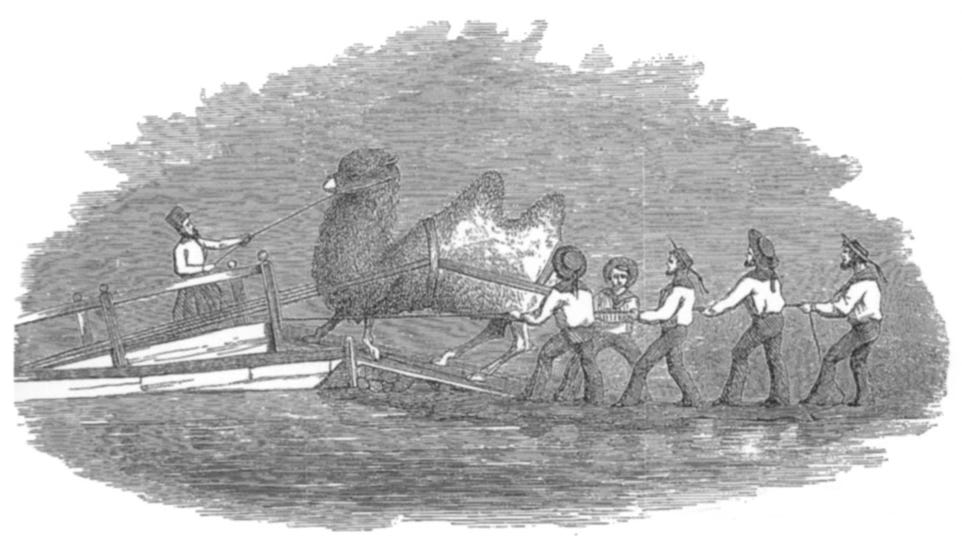

Davis ordered Major Henry Wayne to procure the animals. Wayne traveled to Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia, and Turkey and purchased thirty-four camels, hiring three Arabs in Egypt as drivers and two Turks in Smyrna as saddle makers. The camels were transported by USS Supply, under the command of Navy Lieutenant David P. Porter. The Supply arrived at the port of Indianola (present-day Port Lavaca) on May 14, 1856. Once the animals were offloaded, Porter sailed back to the Middle East and purchased an additional forty-one camels, arriving back in Texas on February 10, 1857.

Wayne marched his original thirty-four beasts from Indianola to a location between Boerne and Kerrville where he established a khan or camel corral (caravansary), which on July 8, 1856, became Fort Verde. For the next ten years, Fort Verde served as the headquarters of the Army Camel Corps. The animals were used to ferry supplies to and from San Antonio, home of the Department of the Army in Texas, as well as taking part in three long-distance expeditions into the west.

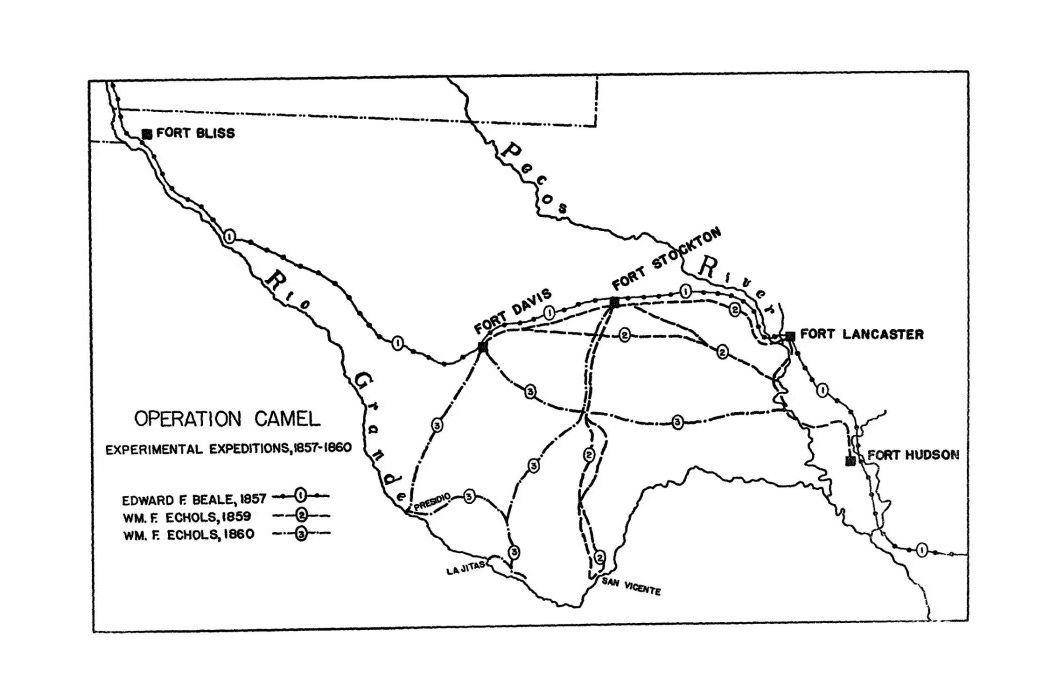

The 1857 Beale Expedition

The first expedition, under the command of Edward Fitzgerald Beale, set out from San Antonio on June 15, 1857, with twenty-five camels carrying six hundred pounds each, including water barrels for troopers and troop stock. The expedition was charged with surveying what became known as the 35th Parallel Wagon Road—later known as historic Route 66. They traveled west along the San Antonio-El Paso Road through Fort Davis and El Paso del Norte, moving up the Rio Grande to Albuquerque, passing through Zuñi territory to Fort Defiance, in western New Mexico, and onto Fort Tejon, north of Los Angeles, California. Describing how his camels handled the brutality of the Trans-Pecos, Beale wrote in his journal:

The character of the road is exceedingly trying to brutes of any kind. . . . The camels . . . have not evinced the slightest distress or soreness; and this is all the more remarkable as mules or horses, in a very short time get so sore-footed that shoes are indispensable. The road is very hard and firm, and strewn all over is a fine, sharp, angular, flinty gravel—very small, about the size of a pea—and the least friction causes it to act like a rasp upon the opposing surface. The camel has no shuffle in his gait, but lifts his feet perpendicularly from the ground, and replaces them without sliding, as a horse or other quadrupeds do.

Beale was so impressed with his camels he said:

Without the aid of this noble and useful brute, many hardships which we have been spared would have fallen our lot; our admiration for them has increased day by day. . . . At times I have thought it impossible they could stand the test to which they have been put, but they seem to have risen equal to every trial, and to have come off every exploration with as much strength as before starting. . . . My only regret is I have not doubled the number.

A. A. Gray, writing in 1930 in the California Historical Society Quarterly, said, “[Beale] had driven his camels more than 1,200 miles, in the heat of summer, through a barren country where feed and water were scarce, and over high mountains where roads had to be made in the most dangerous places. . . . He had accomplished what most of his closest associates said could not be done.”

The 1859 Echols/Hartz Expedition

The second expedition, led by Lieutenants William E. Echols and Edward Hartz, departed San Antonio in early May, 1859. Echols, a U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, accompanied by an escort under the command of Hartz, was ordered to survey the Trans-Pecos from the Comanche Trail—a network of hunting trails carved by generations of mounted warriors—from where it crossed the San Antonio-El Paso Road southward to the Rio Grande. They had a pack train of twenty-four camels and as many mules. The camels carried fodder for the mules, as well as water for the stock and the men. The camels carried no provisions for themselves. They subsisted on ocotillo, creosote, prickly pear, and catclaw, drinking whatever surface water could be found.

Some mules had to be abandoned because they had worn through their metal shoes and couldn’t be replaced. The camels’ feet also suffered, Echols reported, but continued on and eventually healed. After following hundreds of miles along the Comanche Trail and surveying the area, Echols and Hertz arrived at Fort Stockton with all their camels accounted for. Echols wrote, “If it were not for the camels, surely our expedition would have failed.” And Hartz recorded in his journal: “The patience, endurance and steadiness which characterize the performance of the camels during this march is beyond praise, and when compared with the jaded and distressed appearance of the mules and horses, established for them another point of superiority.”

The 1860 Echols Expedition

The third and final long-distance expedition was under Lieutenant Echols’s command once more. On May 31, 1860, Colonel Robert E. Lee, commandant of the Department of Texas, ordered Echols to venture into the Big Bend region from Fort Davis to the Rio Grande, one of the most hostile environments in the United States. He took an equal amount of camels and mules: twenty-five each. The undertaking proved arduous on both men and animals.

The expedition passed through a trail-less wilderness interlaced with mountains, arroyos, canyons, and buttes, becoming rougher and sparser with each passing mile. Grass, what there was of it, was dry and dead—then disappeared all together. No water. Echols recorded: “The mules will not fare well, the camels have performed most admirably today. No such march as this could have been made with any security without them. It is with difficulty that the mules can be kept from the water barrels [carried by the camels], particularly when the water is being issued. I might say the same of the men.”

The expedition endured nearly four months of such barren harshness before reaching Fort Stockton. They had lost nine mules but no camels. When Lee received Echols’s report he commended the “endurance, docility and sagacity” of the camels.

Camels were not without their headaches, however. They were stubborn and ill-tempered, making it difficult for horse soldiers to handle. They also terrified horses and mules. They stunk. And their gait, in the saddle, could induce seasickness.

During the Civil War eighty camels and two Egyptian drivers were conscripted into the Confederate army, packing salt from the flats above Brownsville and carrying cotton into Matamoros, Mexico, but the animals soon fell out of favor. After the War anything championed by Jefferson Davis was considered anathema, including the camel corps. It was abandoned in 1866. Many of the camels were auctioned off to private owners. Sixty-six going to Bethel Coopwood of San Antonio, for $31 each, who then sold some of the animals to circuses. Others were used to ship supplies between Laredo and Mexico City.

* John Russell Bartlett, a member of the United States Boundary Commission following the Mexican-American War, was under orders from President James K. Polk to carry out the provisions of the Treaty of Hidalgo and survey the border between Mexico and the U.S. He was also convinced camels would be ideal pack animals for the forage depleted lands of the high desert of far West Texas.

Gerry Doyle, Camels in Texas (n.p.: The San Jacinto Museum of History Association, 1956).

Chris Emmett, Texas Camel Tales, reprint of original 1932 edition (Austin: Steck-Vaughn Company, 1969).

Chris Heller, “Whatever Happened to the Wild Camels of the American West?” Smithsonian Magazine, August 6, 2015.

Frank Bishop Lammons, “Operation Camel: An Experiment in Animal Transportation in Texas, 1857–1860,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, vol. 61, no. 1 (July 1957), 20–50.

Y’allogy is an 1836 percent purebred, open-range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is created by a living, breathing Texan—for Texans and lovers of Texas—and is free of charge. I’d be grateful, however, if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber and/or purchasing my novel.

Be brave, live free, y’all.

They are ill tempered and even spiteful but very suited for survival West of the Pecos. There is water out there but you have to know exactly where to find it. During the initial exploration I'm sure they missed the remnants of ice age forests atop the desert peaks. Great beauty and a silent desolation to inspire any prophet. If you cannot hear the still small voice there then you're deaf both inside and out. That forbidding part of Texas is is home of my soul and an inspiration to me. Climb a peak out there and see forever. Find a silence that will sing.