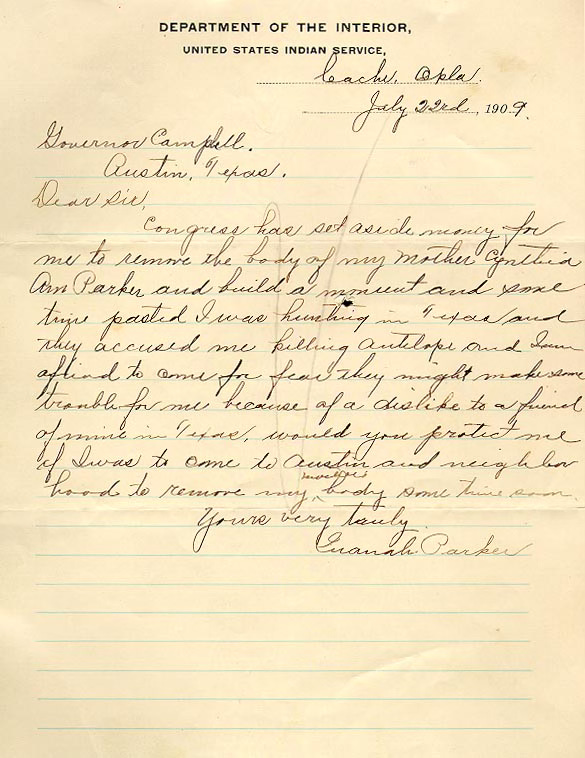

Quanah Parker Asks for the Body of His Mother

Would you protect me if I was to come to Austin . . . to remove my mother’s body some time soon.

Quanah Parker

Life on the Texas frontier was fraught with dangers. The greatest among them was the terror of Indian raids

especially from Comanches. That fear was realized by the Parker family on May 19, 1836, when a coalition of Kiowa and Comanche braves raided a settlement situated on the Navasota River in Limestone County (near present-day Groesbeck) known as Fort Parker. A number of settlers were killed. Five were taken: Elizabeth Kellogg, probably in her thirties, seventeen-year-old Rachel Parker Plummer and her fourteen-month-old son James Pratt, as well as seven-year-old John Richard Parker and his nine-year-old sister Cynthia Ann. Though Rachel and her son’s story is harrowing, Cynthia Ann’s story became the stuff of Texas lore.

While her brother John Richard was ransomed from the Comanches in late 1842, Cynthia Ann grew up among them and became throughly Comanche. She was given the name Nautdah—“Someone Found”—and married the warrior Peta Nocona.

Twenty-four years later, on December 18, 1860, Texas Rangers under the command of Lawrence Sullivan Ross raided the then thirty-three-year-old Nautdah’s camp. Though she had the appearance and bearing of a Comanche, her blue eyes identified her as a white captive. “Rescuing” her from what whites considered a fate worse than death, the Rangers returned Cynthia Ann, and her two-year-old daughter Prairie Flower (Toh-tsee-ah), to her white family. But to Cynthia Ann a life among white society was a fate worse than death. It certainly was one of misery. Prairie Flower died in 1863 and was buried in Asbury Cemetery in Van Zandt County. Cynthia Ann only lived another eight years, starving herself in 1871. She was buried in Fosterville Cemetery in Anderson Country.

Quanah was twelve-years-old when his mother and sister were taken from him. He grew to become a great warrior, the last chief of the Comanches. When he discovered the locations of their gravesites, he petitioned Texas governor Thomas Mitchell Campbell for permission to have their remains removed to Post Oak Mission Cemetery in Indiahoma, Comanche County, Oklahoma.

Department of the Interior

United States Indian Service

Cache, Okla.

July 22nd, 1909

Governor Campbell

Austin, Texas

Dear Sir,

Congress has set aside money for me to remove the body of my mother Cynthia Ann Parker1 and build a monuent and some time pasted I was hunting in Texas and they accused me killing antelope and I am afriad to come for fear they might make some trouble for me because of a dislike to a friend of mine in Texas.2 Would you protect me if I was to come to Austin and neighborhood to remove my mother’s body some time soon.3

Yours very truly

Quanah Parker

Quanah selected the site for the burial of his mother and sister. He chose the lot next to his mother for his own resting place. When the remains of Cynthia Ann and Prairie Flower were reinterred at Post Oak Mission Cemetery, on December 4, 1910, Quanah hosted a memorial service. He delivered the following remarks in English to the whites and Indians in attendance.

Forty years ago my mother died. She captured by Comanche, nine years old. Love Indian and wild life so well no want to go back to white folks. All same people any way, God say. I love my mother. I like white people. Got great heart. I want my people follow after white way, get educate, know work, make living when payments stop. I tell um they got to know pick cotton, plow corn. I want um know white man’s God. Comanche may die tomorrow, or ten years. When end come then they all be together again. I want to see my mother again. That’s why when Government United States give money for new grave I have this funeral and ask white folks to help bury. Glad to see so many my people here at funeral. That’s all.

Quanah lived only a few months after this ceremony. He died on February 23, 1911, and was buried next to his mother. In 1957, Quanah’s, Cynthia Ann’s, and Prairie Flower’s bodies were relocated to the Chief’s Knoll in the Fort Sill Cemetery, in Lawton, Oklahoma.

1 On March 3, 1909, Congress approved an authorizing for the Secretary of the Interior to apportion a thousand dollars for the removal of the bodies of Cynthia Ann Parker and Prairie Flower, her daughter and Quanah’s sister, from Texas to Oklahoma. Of the total amount, not over two hundred dollars was to be expended for the actual removal of the bodies. The rest was to be used for a granite monument and iron fence. Congressman John Stephens of Texas introduced the bill and Quanah Parker lobbied hard for its support.

2 The friend of which he spoke is unknown, but on the issue of killing an antelope the Texas state legislature passed a law on April 19, 1907, making it illegal to kill antelope outside of the months of November and December, the limit of which was two animals per person each year.

3 Oklahoma historian Paul Wellman argued Quanah didn’t actually travel to Texas to oversee the removal of his mother’s and sister’s remains. Biographer S. C. Gwynn disagrees: “[Quanah] traveled to Texas, met some of his white family, and found the cemetery where she lay” and accompanied her body, and Prairie Flower’s, back to Oklahoma.

Daniel A. Becker, “Comanche Civilization with History of Quanah Parker,” Chronicles of Oklahoma, vol. 1 (1921–1923), Oklahoma Historical Society, 247.

Quanah Parker to Thomas Mitchell Campbell, July 22, 1907, in James M. Day, “Two Quanah Parker Letters,” Chronicles of Oklahoma, vol. 44, no. 3 (Fall 1966), Oklahoma Historical Society, 318. Parker’s original handwritten letter can be found at the Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

S. C. Gwynn, Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History (New York: Scribner, 2010), 316–7.

Paul I. Wellman, “Cynthia Ann Parker,” Chronicles of Oklahoma, vol. 12, no. 3 (June 1934), Oklahoma Historical Society, 163–70.

Y’allogy is an 1836 percent purebred, open-range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is created by a living, breathing Texan—for Texans and lovers of Texas—and is free of charge. I’d be grateful, however, if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber and/or purchasing my novel.

Be brave, live free, y’all.

Nice post!

When Quanah’s good friend Charles Goodnight heard about the plans to bury Quanah next to his mother, he wrote, “It is proper that he should be buried by his mother as he, one time, had six wives and . . . could not easily be buried by the side of all.”

Hey Derrick, do you know anything about The Texas Devils? I was researching the outfit last year and didn’t find too much about them except they were a mean bunch of Rangers. But I am English so I don’t have much to go on here. The internet was a bit sparse.