Our Brave Little Band

“Col. Neill & Myself have come to the solemn resolution that we would rather died in these ditches than give it up to the enemy.”

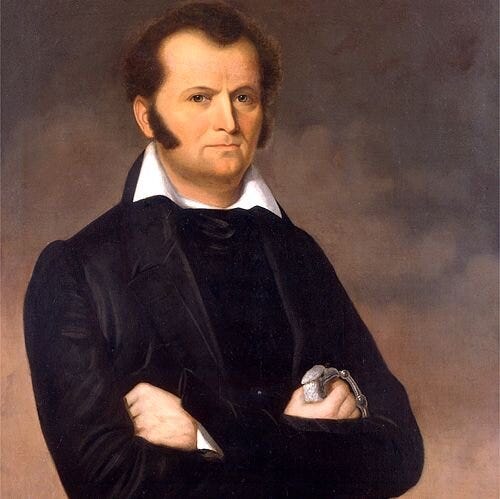

James Bowie

In John Wayne’s 1960 version of The Alamo, James Bowie, played by Richard Widmark, is adamant that the Alamo should be destroyed and that the Texas volunteers adopt a guerrilla-style campaign against the Mexican army. This position becomes the basis of the conflict between Bowie and William B. Travis, portrayed by Lawrence Harvey.

Wayne’s depiction of what took place at the Alamo in February and March 1836 is more myth making than historical fact, but Bowie’s claim that it would be best to blowup the Alamo does have some historical justification. On January 17, 1836, Bowie and General Sam Houston, who was in overall command of Texas’s fledgling army, were together at Goliad. Bowie was ordered to San Antonio Bexár with anywhere from thirty to fifty men to reinforce the small contingent there under the command of James C. Neill. Houston sent a dispatch to Governor Henry Smith, which read in part:

Colonel Bowie will leave here in a few hours for Bexár with a detachment of from thirty to fifty men. Capt. Patton’s Company, it is believed, are now there. I have ordered the fortification in the town of Bexár to be demolished, and if you should think well of it, I will remove all the cannon and other munitions of war to Gonzales and Capano, blow up the Alamo and abandon the place, as it will be impossible to keep up the Station with volunteers, the sooner I can be authorized the better it will be for the country [emphasis mine].

Sam Houston thought it best to strip the Alamo of its munitions, destroy it, and repost its garrison at Gonzales and Capano. But, it appears, he would take no action until he received authorization from Governor Smith. Bowie obviously knew Houston’s mind on the matter.

Bowie arrived in Bexár the following day and was greet by Colonel Neill. No doubt Bowie conveyed Houston’s thinking about the fate Alamo, but would have also told Neill that the General was awaiting consent from the government. Neill, for his part, had no attachment to Bexar or to the Alamo—though he had done much to turn the old mission into a fort. In a letter written to Governor Smith on January 23, 1836, Neill said, “If teams [of draft horses and/or oxen] could be obtained here by any means to remove the Cannon and Public Property I would immediately destroy the fortifications and abandon the place, taking the men I have under my command here, to join the Commander in chief at Capanoe [sic], of which I informed him last night.”

Unfortunately, there was not a single draft animal to be found in San Antonio after the ill-fated Matamoros Expedition absconded with them all. So even thought Neill was of the same mind of Houston, he could not have moved his whole garrison with either abandoning the munitions at the Alamo to the enemy or destroying them along with the Alamo. Either way, much needed weaponry and powder would be lost to the Texian cause.

Bowie was impressed with what he saw at the Alamo. Though the men languished under considerable hardships—their clothing was all but threadbare, they had not been paid in months, and foodstuffs were not ideal—their esprit de corps was high, which was a testament to Neill’s leadership. Bowie began to have second thoughts about leaving the Alamo in ruins. And in fact, within a matter of weeks he and Neill abandoned the idea of blowing up the Alamo, as Bowie’s letter to Governor Smith on February 2, 1836, attests.

Bejar 2d Feby 1835 [1836]

To His Excy. H Smith

Dear Sir

In pursuance of your orders, I proceeded from San Felipe to La Bahia and whilst there employed my whole time in trying to effect the objects of my mission. You are aware that Genl Houston came to La Bahia soon after I did, this is the reason why I did not make a report to you from that post. The Comdr. in Chf. has before this communicated to you all matters in relation to our military affairs at La Bahia, this make it wholly unnecessary for me to say any thing on the subject. Whilst at La Bahia Genl Houston received despatches from Col Comdt. Neill informing that good reasons were entertained that an attack would soon be made by a numerous Mexican Army on our important post of Bejar. It was forthwith determined that I should go instantly to Bejar; accordingly I left Genl Houston and with a few very efficient volunteers came on to this place about 2 weeks since. I was received by Col Neill with great cordiality, and the men under my command entered at once into active service. All I can say of the soldiers stationed here is complimentary to both their courage and their patience. But it is the truth and your Excellency must know it, that great and just dissatisfaction is felt for the want of a little money to pay the small but necessary expenses of our men. I cannot eulogise [sic] the conduct & character of Col Neill too highly: no other man in the army could have kept men at this post, under the neglect they have experience. Both he & myself have done all that we could; we have industriously tryed [sic] all expedients to raise funds; but hitherto it has been to no purpose. We are still labouring night and day, laying up provisions for a siege, encouraging our men, and calling on the Government for relief.

Relief at this post, in men, money, & provisions is of vital importance & is wanted instantly. Sir, this is the object of my letter. The salvation of Texas depends in great measure in keeping Bejar out of the hands of the enemy. It serves as the frontier picquet [sic] guard and if it were in the possession of Santa Anna there is no strong hold from which to repell [sic] him in his march towards the Sabine. There is no doubt but very large forces are being gathered in several of the towns beyond the Rio Grande, and late information through Senr Cassiana & others, worthy of credit, is positive in the fact that 16 hundred or two thousand troops with good officers, well armed, and a plenty of provisions, were on the point of marching, (the provisions being cooked &c). A detachment of active men from the volunteers under my command have been sent out to the Rio Frio; they returned yesterday without information and we remain yet in doubt whether they entend [sic] an attack on this place or go to reinforce Matamoras. It does however seem certain that an attack is shortly to be made on this place & I think & it is the general opinion that the enemy will come by land. The Citizens of Bejar have behaved well. Col. Neill & Myself have come to the solemn resolution that we would rather die in these ditches than give it up to the enemy. These citizens deserve our protection and the public safety demands our lives rather than to evacuate this post to the enemy. — again we call aloud for relief; the weakness of our post will at any rate bring the enemy on, some volunteers are expected: Capt Patton with 5 or 6 has come in. But a large reinforcement with provisions is what we need.

James Bowie

I have information just now from a friend whom I believe that the force at Rio Grande (Presidia) is two thousand complete; he states further that five thousand more is a little back and marching on, perhaps the 2 thousand will wait for a junction with the 5 thousand. This information is corroberated [sic] with all that we have heard. The informant says that they intend to make a decent [sic] on this place in particular, and there is no doubt of it.

Our force is very small, the returns this day to the Comdt. is only one hundred and twenty officers & men. It would be a waste of men to put our brave little band against thousands.

We have no interesting news to communicate. The army have elected two gentlemen to represent the Army & trust they will be received.

James Bowie

Colonel Neill was not at the Alamo when it fell to Mexican forces under the command of Santa Anna on March 6, 1836. Neill had received permission for a twenty-one day leave to attend to a personal matter—a sickness in his family—and left the garrison for Bastrop on February 11. Until his return, Neill placed Travis in temporary command. Neill never made it back to Bexár. He did, however, command the Twin Sisters—two match six-pounders—on April 20, in the skirmish that preceded the battle of San Jacinto. During this engagement, his artillery corps repulsed the Mexicans who were attempting to probe the woods that concealed the main Texian army. Neill was severely wounded in the hip from a canister blast preventing him from taking part in the decisive battle that won Texas’s independence.