On the Naming of the Gulf of Mexico

I'll continue to call the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of Mexico. –Derrick G. Jeter

Y’allogy is an 1836 percent purebred, open-range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is free of charge, but I’d be grateful if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber.

A note of explanation: Longtime readers of Y’allogy know I rarely engage in political matters, unless it touches upon Texas history. While the subject of this article is historical and touches upon Texas in a sort of way the conclusions I draw are nothing short of political. I chose not to write on this topic when many were offering hot takes, spurring hobbyhorses over cliffs. I wanted time for things to cool and make sure I wasn’t simply riding my own personal hobbyhorse. This reflects my thinking over these many months.

Within a matter of hours of being sworn in as the forty-seventh President of the United States of America, on January 20, 2025, Donald J. Trump signed more than forty Executive Orders (EO). One of them, EO 14172, “Restoring Names That Honor American Greatness,” calls for Mount Denali to be renamed Mount McKinley (§3) and the Gulf of Mexico to be renamed the Gulf of America (§4). Section 1, “Purpose and Policy,” outlines the reason for these name changes:

It is in the national interest to promote the extraordinary heritage of our nation and ensure future generations of American citizens celebrate the legacy of our American heroes. The naming of our national treasures, including breathtaking natural wonders and historic works of art, should honor the contributions of visionary and patriotic Americans in our nation’s rich past.

Thirteen years earlier, Mississippi state representative Steve Holland introduced a bill to rename the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of America. But where Holland was sarcastic, protesting what he saw as xenophobic and jingoistic legislation, Trump was serious.

A state legislative body, even from a state boarding the Gulf, doesn’t have the authority to rename an international body of water.1 Neither does the President of the United States nor Congress—at least in terms of changing the Gulf’s international identification.2 Other nations are not obligated to call the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of America—to change their maps or alter diplomatic documents. In fact, different countries often identify bodies of water or waterways by different names. The river designating the border between the United States and Mexico is such a case. In the United States it’s called the Rio Grande—the great or big river. In Mexico it’s called the Rio Bravo (sometimes Rio Bravo del Norte)—the brave or fierce river (of the north). The name change from the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America only applies to the federal government of the United States—to its maps and papers. It has no binding effect on individual states, private organizations (such as the Associated Press, which refused to revise its style guide), or to citizens of the United States.

We can call the Gulf whatever we want. And at Y’allogy, whenever I’m not referring to the body of water bordering Texas to the south, Mexico to the west, and Florida to the east as the Gulf or the Coast, it will be called the Gulf of Mexico.

Some might ask, Why? Why not follow Trump’s lead and call it the Gulf of America?

It’s not in my nature to jump on bandwagons or fall in line—that’s the Texan in me. Aside from my mulishness, however, I have three reasons not to call the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of America.

First, the executive order offers no compelling historical reason to rename the Gulf of Mexico. There’s an old axiom, “Don’t take down the fence until you know the reason it was put up.” The fence might be there to keep your cattle from eating your neighbor’s grass or to keep your neighbor’s cattle from eating your grass. In the same way, don’t change historic names until you know the history of those names. Learning the history of how the Gulf of Mexico got its name might lead to greater historic intelligence while changing it to the Gulf of America might lead to greater historic ignorance.

Contrary to what some believe, the Gulf of Mexico was not named by Mexico. The Aztecs, the original inhabitants of what would become the country of Mexico, called the Gulf and the Pacific Ocean “Sky Water” because the distinction between sea and sky disappeared over the long horizon. The Mayans, who lived in present-day southern Mexico and Central America, referred to the Gulf as “the red place,” likely because of the reflected sunset upon the water. During the Age of Discovery, bodies of water were often named after destination points by dominant nations as a means of declaring sovereignty over subordinate nations. The Bight of Benin wasn’t named by the people of the Benin kingdom, it was named by Europeans who sailed across the bight (an old English word for bay) to reach Benin. The same is true for the Indian Ocean, the Java Sea, the Irish Sea, and the Gulf of Finland.

The Gulf of Mexico was named by the Spanish because it was the sea they crossed to arrive at New Spain—Mexico, which they learned was a Náhuatl word (the language spoken by the Aztecs), derived from metztli (moon), xictli (navel), and co (place)—the navel of the moon. The Aztecs referred to themselves as the Mēxihcah.

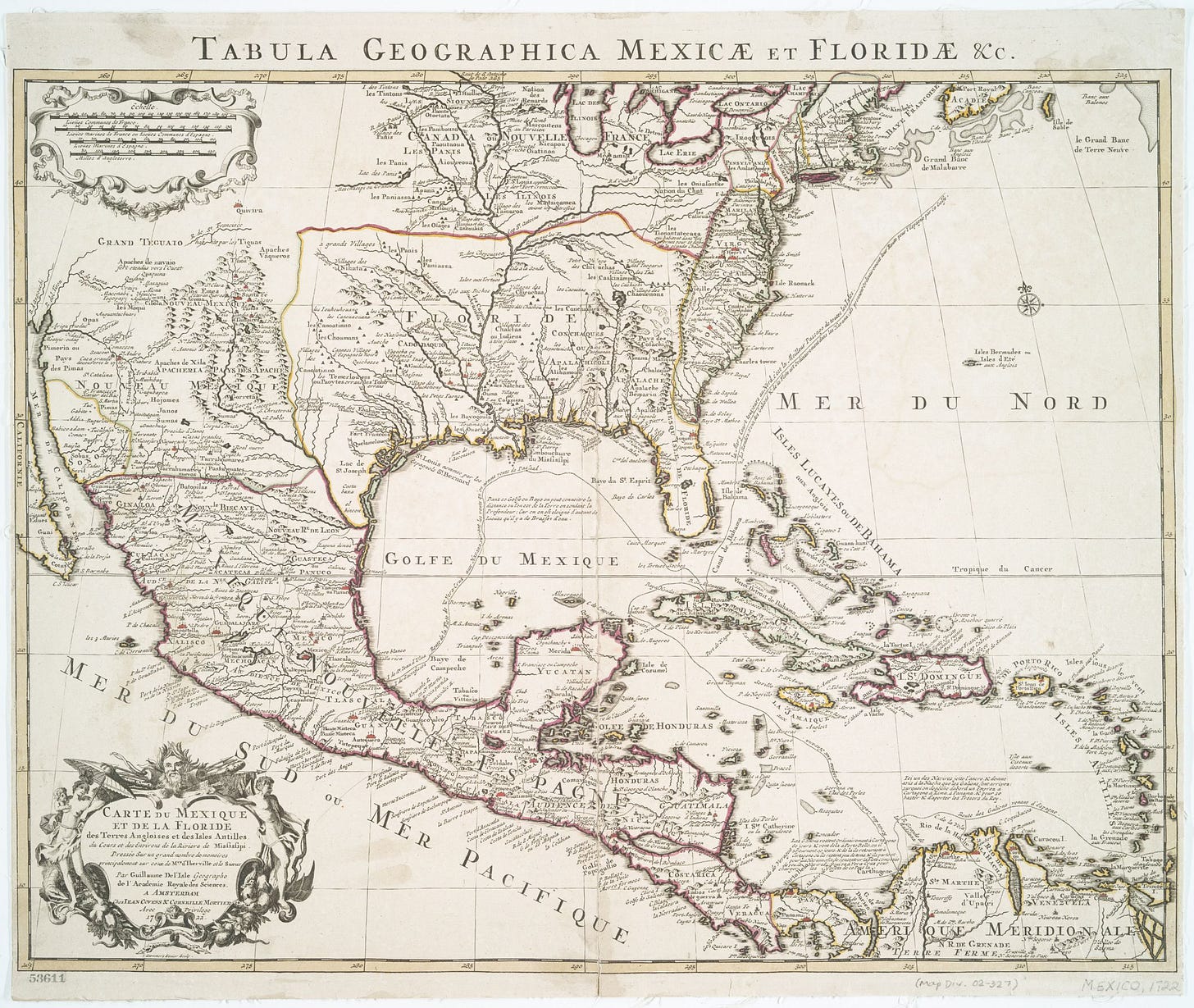

The first explorer to circumnavigate the Gulf was Alonzo Álvarez de Pineda in 1519—the first also to sail the Texas coast. He produced a crude map of the Gulf region, with a workable outline of the coastline from Mexico to Florida, identifying a number of tributaries, including the Mississippi River, which he named Esparto Santo. He didn’t name the Gulf. Hernán Cortés, who conquered the Aztecs for the Spanish crown (1519–1521), called the Gulf Mar del Norte—“The North Sea.” Others referred to the Gulf by other names. The Italian cartographer Sebastian Cabot (1544) called it Golpho de la Nueva España—“Gulf of New Spain.” Diogo Homen, Portuguese mapmaker, gave it perhaps the most uncreative name of all: Sinus Magnus Antiliarum—“Large, Round Bay” (1558).

The first time the Gulf’s name was associated with Mexico was in 1541 when an unknown mapmaker dubbed it Seno de Mejicano—“The Mexican Sound.” Since then, other mapmakers and writers have associated the Gulf with Mexico. Italian cartographer Baptista Brazio, who created a map for Sir Francis Drake’s 1585–1586 naval campaign against Spanish colonial holdings in the Americas, called it the Baye of Mexico. Englishman Richard Hakluyt, in his collection of naval explorations, Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, and Discoveries of the English Nation (1589), labeled it the Bay of Mexico. The first appearance of Golfo de México on a world map, however, was in 1550.3

And so it has been called since—that is until January 20, 2025.

Naming is an act of sovereignty. Historically, however, when it came to naming bodies of water the sovereign act was always stamped upon a conquered people by a conquering people. In an act of historic irony, by the stroke of his pen, Trump has, in the words of David Frum, reduced the United States to “a country that [no longer] stamps itself upon history, but a country upon which history is stamped.”

Second, the executive order offers no compelling patriotic reason to rename the Gulf of Mexico. No doubt the executive order is couched in patriotic sounding language, but patriotism is more than shouting “USA, USA, USA!” and hugging the American flag. Patriotism means to love the country for what it has been, what it is, and what it can be, but only when it promotes the “better angels of our nature.” Patriotism also means to loath our country’s sins—past and present—and to labor to rectify those sins by forming “a more perfect union” in the present and future.

As it is, the patriotic sounding phrases in the executive order do none of these things. In truth, the language is so vague as to render its purpose devoid of meaning. Nothing in this executive order accomplishes its stated goal—to “ensure future generations of American citizens celebrate the legacy of our American heroes” and to “honor the contributions of visionary and patriotic Americans in our nation’s rich past.” One could perhaps make an argument the renaming of Denali fulfills this purpose, since its name change is in honor of an individual American—President William McKinley. But that’s not the case with renaming the Gulf of Mexico. American children, to say nothing of Americans generally, today or in generations to come, learn nothing about America or her visionary and patriotic citizens simply by stamping “America” on a body of water.

To put a finer point on it, the language of the executive order speaks of “American heroes” and of “visionary and patriotic Americans.” It speaks of the specific—of individuals—in general terms. What visionary or patriotic American hero is in view with the renaming of the Gulf of Mexico? This is the language of patriotism in shadow not substance. Some may argue I’m being overly literal and critical. “It’s just semantics,” you might say. “We all know what’s meant. The important thing is to focus on the spirit of the language.” Ah, no. If I write a love letter to my wife and say, “I loath you” instead of “I love you,” I assure you I can’t make the argument—even for a notoriously poor speller like myself—“What difference does it make, sweetheart? It’s just spelling. You know what I mean.”

Here’s the rub: You cannot honor those whom you do not name by name. It’s that simple.

Third, the executive order offers no compelling political reason to rename the Gulf of Mexico. Renaming the Gulf is politically decontextualized. It asserts no political or legal authority or rights to the United States vis-à-vis Mexico, or any other nation. No one was yammering for it to be renamed—no petitions from Congress or citizens were calling for a new designation. So why go to the bother, and the expense of renaming government maps and documents?

I believe the answer is twofold. First, this executive order represents one man’s antipathy toward Mexico. Second, this man truly believes this silly little piece of shibboleth is a grand statement of American glory and that all Americans ought to agree with it. It’s not and I don’t. It’s small and petty. So, as a principled conservative, I reject it and will practice the first principle of conservatism: to conserve. As a true Texan, following in the footstep of my forebears, I draw a line in the sand and will continue to call the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of Mexico.4

1 Though a state doesn’t have the authority to rename an international body of water, it can call for a name change in regards to its own documents. That’s what Texas sate senator Mayes Middleton of Galveston has done. He introduced Senate Bill 1717 in the Texas senate to rename the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America in all official references made by state agencies, resolutions, rules, or publications. The bill pass in the senate 31 to 20. As of this writing, it awaits a vote in the House State Affairs Committee.

2 On May 8, 2025, the United States House of Representatives, in a party-line vote (211 to 206), passed H.R. 276, “The Gulf of America Act,” renaming the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of America. As of this writing, it awaits a vote in the U.S. Senate.

3 The word “gulf” comes from the Latin gulphus, indicating a body of water partially enclosed by land. The French picked up on the Latin and the word evolved into golfe. In Spanish it became golfo or golpho.

4 On a more humorous note, Don Solomon offers other possibilities for renaming the Gulf. See “If We’re Renaming the Gulf of Mexico, Let’s Consider All the Options,” Texas Monthly, January 28, 2025.

Jack E. Davis, The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017), 41–50.

Paul S. Galtsoff, “Historical Sketch of the Explorations of the Gulf of Mexico,” in Gulf of Mexico: Its Origin, Waters, and Marine Life, Fishery Bulletin of the Fish and Wildlife Service, vol. 55, United States Department of the Interior (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1954), 3–36.

The 1836 Percent Y’allogy Guarantee: This newsletter is created by a living, breathing Texan—for Texans and lovers of Texas. It exists thanks to the generosity of its readers. To ensure it continues, I invite you, if you’re able and haven’t already done so, to ride for the brand as a paid subscriber, give the gift of Y'allogy to a fellow Texan, or purchase my novel.

Much obliged, y’all.

I thought there was more Gulf between Yucatan and Cuba than that, but Grok says it’s 130 miles.

Love the map!