On the Death of Deets

“I don’t want to start thinking about all the things we should have done for this man.” –Augustus McCrae, Lonesome Dove

Y’allogy is an 1836 percent purebred, open-range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is free of charge, but I’d be grateful if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber.

Warning: If you haven’t read Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove or seen the miniseries based on it but plan to, you might not want to read this article. There are spoilers ahead.

It’s a common confusion among Lonesome Dove fans that Larry McMurtry fashioned his fictitious characters Captain Woodrow F. Call and Captain Augustus “Gus” McCrae on the historic characters Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving. Readers reach this conclusion because McMurtry has Call toting Gus’s body from Montana back to Texas for burial, something Goodnight did for his friend and partner Loving—though in that case the distance was much shorter: from New Mexico to Texas. Not to dig a gopher hole along the trail of those riding this hobbyhorse, but McMurtry did not develop Call and Gus from Goodnight and Loving. He modeled his characters on two other literary figures: Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.

Though Call and Gus aren’t based on Goodnight and Loving, Joshua Deets, the black Ranger skilled in all manner of frontier arts, is patterned on the real life Bose Ikard, the dependable cowhand who rode with Goodnight. “There was a dignity, a cleanliness, and a reliability about him that was wonderful,” Goodnight wrote after Ikard passed away in 1929.

His behavior was very good in a fight, and he was probably the most devoted man to me that I ever had. I have trusted him further than any living man. He was my detective, banker, and everything else in Colorado, New Mexico, and the other wild country I was in.

We went through some terrible trials during those four years on the trail. While I had a good constitution and endurance, after being in the saddle for several days and nights at a time, on various occasions, and finding I could stand it no longer, I would ask Bose if he would take my place, and he never failed to answer me in the most cheerful and willing manner, and was the most skilled and trustworthy man I had.”

Lonesome Dove puts into action a number of these descriptions of Ikard with Deets at the center of the action. Early in the novel, McMurtry writes, “Deets was a black man. He had been with Call and Augustus nearly as long as Pea Eye. Three days before, he had been sent to San Antonio with a deposit of money, a tactic Call always used, since few bandits would suspect a black man of having any money on him.” Later, while crossing a waterless wasteland, Call pushes the Hat Creek outfit to reach a creek. Call hadn’t slept in three days when he nodded off horseback. McMurtry notes, “When [Call] opened his eyes he saw the Texas bull trot past him. He reached for his reins but they were not there. His hands were empty. Then, to his amazement, he saw Deets had taken his reins and was leading the Hell Bitch,” Call’s horse. When Deets saw Call was awake, he gave the reins back to his boss: “‘Didn’t want you to fall and get left, Captain.’”

The closest link between Deets and Ikard, however, involves the death of both—not in their manner but in the messages on their grave markers. Ikard died on January 4, 1929, from influenza, in Texas. Deets died on some unspecified summer afternoon sometime in the late 1870s, from an act of violence, in Wyoming.

The morning after the Hat Creek crew found water they discovered several horses stolen from their remuda. Call and Gus, along with Deets tracking, rode from camp in search of the thieves. Deets found them in a draw. “‘Mostly women and children,’” he reported. They were Indians—and starving. They stole the horses for food. To scare them away, Call pulled his pistol and fired. They scattered. But they failed to grab a little boy, who was blind and fell over a pile of bloody guts. Deets picked the boy up. “At that moment there was a wild yell from the teepees and Deets looked up to see one of the young braves rushing toward him,” McMurtry wrote. “Deets held out the baby and smiled. . . . Deets kept holding the baby out toward the tribe and smiling, trusting that the young brave would realize he was friendly. The young man didn’t need his lance—he could just take the squalling baby back to its mother.” When Call, Gus, and Deets realized the young warrior wasn’t going to stop it was too late. Call and Gus shot at the same time, but the young brave had already thrust his lance through Deets’s side and into his chest.

McMurtry makes a subtle shift in the narrative at this point, flipping what we thought we knew about Call and Gus. Throughout Call was the man of action—taciturn and emotionally closed. Gus was the man of inaction—loquacious and emotionally open. Though Deets’s death affects both men, it affects Call the most. The closed-hearted Call takes the baby from Deets, not the open-hearted Gus. The always certain Call “didn’t know what to do.” He asks Gus to remove the lance, instead of doing it himself. Call becomes talkative, Gus remains silent. Though he had dispensed death all his adult life, Call can’t bring himself to believe Deets is dead. He has to asks Gus, “‘Is he dead already?’” “Augustus didn’t answer. He was resting for a moment, wondering if he could get the lance out or if he should just break it off or what.” A man who never doubted himself or blamed himself for the death of men who served under him doubted his slowness to act and blamed himself for Deets’s death. “‘I guess it’s our fault. We should have shot sooner,’” Call said.“‘I don’t want to start thinking about all the things we should have done for this man,’” Gus answered.

When Call and Gus return to the outfit with Deets’s body draped over his saddle the cowboys are shocked. Call and one of the hands dig a grave while Gus wraps Deets in a wagon sheet. Gus then turns away. “‘I hate funerals,’ he said. ‘Particularly this one.’” McMurtry writes:

They expected to start the herd that day, as Captain Call had never been known to linger. But this time he did. He came back from the grave, got a big hammer and knocked a board loose from the side of the wagon. He didn’t explain what he was doing to anyone, and the look on his face discouraged anyone from asking. He took the board and carried it down to the grave. The rest of the day he sat alone by Deets’s grave, carving something into it with his knife. The sun flashed on his knife, and the cowhands watched in puzzlement. They just didn’t know what it could be that would take the Captain so long.

The untalkative Call pours forth words—not with his voice but with his knife. But the talkative Gus is virtually mute. All he says to Newt, the unclaimed orphaned son of Call, “‘Let’s go see what he wrote for old Deets. I’ve seen your father bury many a man, but I never saw him take this kind of pains.’” Here’s what Call wrote:

Josh Deets

Served with me 30 years. Fought in 21 engagements with the Commanche and Kiowa. Cherful in all weathers, never shirked a task. Splendid behaviour.

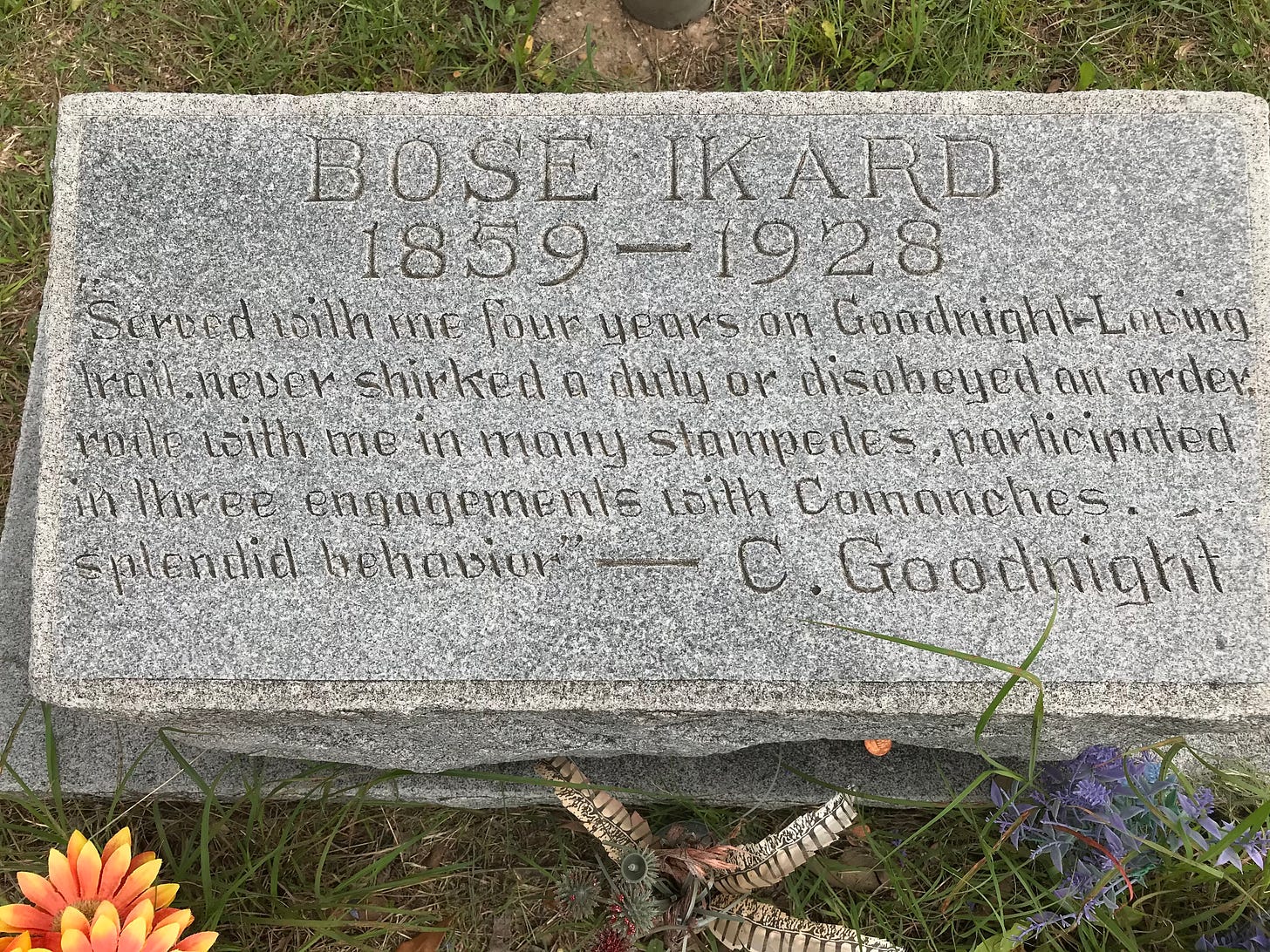

This is nearly a direct quote from the epitaph Goodnight wrote for Ikard:

Bose Ikard

Served with me four years on the Goodnight-Loving Trail, never shirked a duty or disobeyed an order, rode with me in many stampedes, participated in three engagements with Comanches, splendid behavior.

Earlier in the narrative, after the death of a young Irish boy, Gus gave a eulogy but at Deets’s grave he couldn’t speak. He acted. “Augustus took something out of his pocket. It was the medal the Governor of Texas had given him for service on the border during the hard war years. . . . The medal had a green ribbon on it, but the color has mostly faded out. Augustus made a loop of the ribbon and put the loop over the grave board and tied it tightly. Captain Call had walked away.”

And “Augustus followed.”

J. Evetts Hailey, Charles Goodnight: Cowman and Plainsman (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1949), 243.

Larry McMurtry, Lonesome Dove (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985), 18, 690, 695, 697–8, 702.

Bruce M. Shackelford, “Bose Ikard: Splendid Behavior,” in Black Cowboys of Texas, ed. Sara R. Massey (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2000), 137.

The 1836 Percent Y’allogy Guarantee: This newsletter is created by a living, breathing Texan—for Texans and lovers of Texas. It exists thanks to the generosity of its readers. To ensure it continues, I invite you, if you’re able and haven’t already done so, to ride for the brand as a paid subscriber, give the gift of Y'allogy to a fellow Texan, or purchase my novel.

Much obliged, y’all.

Whew. On the page and on the screen, these were powerful moments. Didn’t know about Deets’ real-life inspiration!

Great article - thanks for sharing it.

I loved those books.