On the Death of David Crockett

When no one sees a legend die, then the legend lives.

William C. Davis

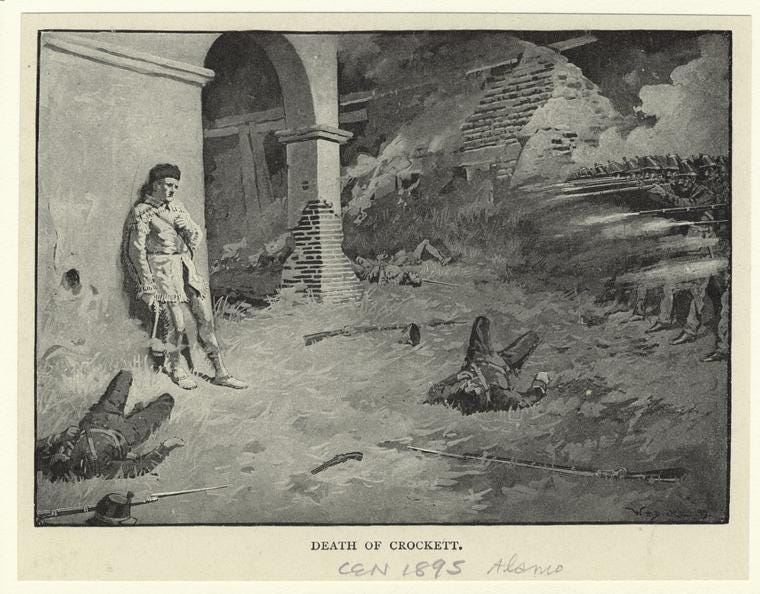

It’s not wise to learn history from movies. This is especially true of the history about the siege and assault of the Alamo. Even less so when trying to ascertain irrefutable facts of how David Crockett died.1 For example, three popular films portray Crockett’s death in three different ways. Walt Disney’s Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier (1955), starring Fess Parker, doesn’t actually show Crockett’s death, but implies he went down swinging “Betsy,” his Kentucky long rifle. John Wayne’s The Alamo (1960), the most famous of the Alamo films, has Crockett blowing himself up, along with the garrison’s powder magazine. The 2004 movie by the same title, starring Billy Bob Thornton, pictures the king of the wild frontier as a prisoner of the Mexican dictator and general Antonio López de Santa Anna, who has Crockett executed.

For years, historians have puzzled over just how Crockett died on that Sunday morning, March 6, 1836. The heroic version depicts him fighting to the last, swinging his rifle, as portrayed by Parker in 1955 and painted by Robert Onderdonk in his 1903 The Fall of the Alamo. Wayne’s “suicidal” version is pure Hollywood bunk. The Thornton version of Crockett surrendering and being put to death, however, does have some historical provenance—sort of. Contrary to popular belief, not all the defenders of the Alamo died in the melee. At least seven were captured or surrendered before the final shot was fired. Each was then executed. Writing from his headquarters in Gonzales on Friday, March 11, Sam Houston informed James Fannin at Goliad that he had “little doubt theAlamo had fallen.” But then added: “After the fort was carried, seven men surrendered, and called for Santa Anna and quarter. They were murdered by his order.”2

Though Houston didn’t mention Crockett by name, a rumor has persisted since 1836 that Crockett was one of the seven, dying either by being shot, bayoneted, or sabered.3 This rumor was invigorated with the 1975 English translation of José Enrique de la Peña’s With Santa Anna in Texas, originally published in Spanish in Mexico City in 1955. De la Peña was an officer in Santa Anna’s Army of Operations and took part in the Alamo assault. De la Peña recounts a speech the General gave immediately after the battle, “lauding [his men’s] courage and thanking them in the name of the country.” Before the speech, however, de la Peña said Santa Anna gave an order that disgusted him.

Shortly before Santa Anna’s speech, an unpleasant episode had taken place, which, since it occurred after the end of the skirmish, was looked upon as base murder and which contributed greatly to the coolness that was noted. Some seven men had survived the general carnage and, under the protection of General Castrillón, they were brought before Santa Anna. Among them was one of great statue, well proportioned, with regular features, in whose face there was the imprint of adversity, but in whom one also noticed a degree of resignation and nobility that did him honor. He was the naturalist David Crockett, well known in North America for his unusual adventures, who had undertaken to explore the country and who, finding himself in Béjar at the very moment of surprise, had taken refuge in the Alamo, fearing that his status as a foreigner might not be respected. Santa Anna answered Castrillón’s intervention in Crockett’s behalf with a gesture of indignation and, addressing himself to the sappers, the troops closest to him, ordered his execution. The commanders and officers were outraged at this action and did not support the order, hoping that once the fury and the moment had blown over these men would be spared; but several officers who were around the president and who, perhaps, had not been present during the moment of danger, became noteworthy by an infamous deed, surpassing the soldiers in cruelty. They thrust themselves forward, in order to flatter their commander, and with swords in hand, fell upon these unfortunate, defenseless men just as a tiger leaps upon his prey. Though tortured before they were killed, these unfortunates died without complaining and without humiliating themselves before their torturers. It was rumored that General Sesma was one of them; I will not bear witness to this, for though present, I turned away horrified in order not to witness such a barbarous scene. Do you remember, comrades, that fierce moment which struck us all with dread, which made our souls tremble, thirsting for vengeance just a few moments before? Are your resolute hearts not stirred and still full of indignation against those who so ignobly dishonored their swords with blood? As for me, I confess that the very memory of it makes me tremble and that my ear can still hear the penetrating, doleful sound of the victims.4

“Everyone wanted to know how Crockett died,” historian William C. Davis wrote. “After all, they knew from Joe [William Barret Travis’s slave] how Travis died, and they knew from several sources how Bowie met his end. But the mystery and uncertainty about Crockett’s death demanded something to fill the void.”5 For many, de la Peña did just that.6 But there’s good reason to be skeptical of the surrender/capture and execution theory, even with de la Peña’s “eyewitness” account.

Crockett’s Attitude the Night Before the Final Battle

While this doesn’t argue directly against the theory that Crockett surrendered, only to be put to the sword (or bayonet), the story (if true) related by Dr. Joseph H. Barnard hardly strikes me as a man looking to save his life at all costs. In a letter written three months after the fall of the Alamo, Dr. Barnard said,

The Americans fought to the last, and were killed to a man. There were several friends who were saved, and who informed me that the men, with the full prospect of death before them, were always lively and cheerful, particularly Crockett, who kept up their spirits by his wit and humor. The night before the storming, he called for his clothes that had been washed, stating that he expected to be killed the next day, and wished to die in clean cloths, and that they might give him a decent burial.7

Crockett’s hope for a “decent burial” went unfulfilled. The bodies of the defenders were consumed on funeral pyres.

Silence of Other Mexican Military Reports8

A more direct argument against the surrender/capture theory are the firsthand accounts written by other Mexican officers that fail to mention Crockett’s execution, including Colonel Juan Nepomuceno Almonte and Ramón Caro, Santa Anna’s personal secretary.

Captain José Juan Sánchez, who stormed the walls of the Alamo, did speak of brutalities he witnessed: “Some cruelties horrified me, among them the death of an old man they called ‘Cochran’ and of a boy approximately fourteen years.” The boy has remained unidentified, though there were a number of young men present, ranging from fifteen to nineteen. The youngest being William Philip King of Mississippi. Concerning “old man . . . ‘Cochran,’” some believe Sánchez, a native Spanish speaker, merely misunderstood the name and must be referring to Crockett, who was forty-nine-years old. Though not “old” at twenty-six, there was a Cochran on the Alamo muster rolls: Robert E. Cochran of New Hampshire. So, did Sánchez mishear the name or misjudge the age of Cochran? Either way, we can’t say with historical certainty that Crockett was the man accompanying the boy to the grave.

Sergeant Manuel Loranca did write of finding “all the refugees which were left” in the convento and Santa Anna’s order that these men be immediately “shot, which was according done.” But, again, he fails to name names—Crockett specifically.

General Vicente Filsola, Santa Anna’s second in command, wrote a detailed account of the campaign and Alamo battle. But Neither he nor those he he interviewed, or who provided written testimony, mentioned someone as famous as Crockett coming before Santa Anna and being put to death.

Santa Anna wrote an after-action account just hours after the bodies began to burn. He failed to mention Crockett’s capture or surrender and execution. He did mention the body of Crockett was “among the corpses,” but that is all. Subsequently, in his lengthy 1837 chronicle of the battle, Santa Anna made no comment on Crockett’s death by execution. Later in life, in his memoirs, Santa Anna said of the rebels, “Not one soldier showed signs of desiring to surrender.” That doesn’t mean some weren’t captured. Some were. But as historian James Donovan notes, “Santa Anna would have been eager to brag about killing such a prominent U.S. citizen, particularly since it would have been further evidence of a claim he was constantly making—that many of the rebels were American citizens,” which he often called “pirates,” and not Texian settlers.

After Texas won independence and became a Republic, Santa Anna came under increasing criticism. The story of such a notable person as Crockett having been captured and put to death on the General’s order would have gone a long way to paint him as little better than a cold-blooded murderer. And yet, none of his critics, even in his own ranks, mentioned Crockett’s surrender or capture and ensuing execution. Nor did it come up (or wasn’t recorded) when Santa Anna was captured on April 22, 1836, after the battle of San Jacinto, and interrogated. Nor did Santa Anna say a word about Crockett’s death, other than he was identified among the rebel dead, during his seven months imprisonment in Texas and the United States.

Problems with the De La Peña Narrative

The de la Peña narrative is often presented as a unique eyewitness account from one officer of the Mexican campaign against the Texians, including the battle and aftermath of the Alamo. This notion has little merit, however, given the fact that the “diary,” begun months after the battle, was reconstructed years later into a memoir in which various Mexican accounts from disparate sources were incorporated, including letters and reports written by Texians such as Travis and Houston. Concerning this, and the subject of Crockett’s death, William Davis wrote, “De la Peña openly admitted that he did not see all that he recounted and that he had adopted the recollections of others. The highly derivative and contradictory nature of his Crockett account suggest powerfully that it is one of those episodes ‘to which I have not witnessed.’”9

Though the material in the de la Peña “diary” is authentic, in that it contains his own account (as well as that of others) written in the years after the battle and before his death in 1840, there are a number of inaccuracies when compared with other verified accounts of the battle’s conclusion. For example, de la Peña claims to have seen Travis, “a handsome blond,” shot in the Alamo courtyard. But no historian disputes the testimony of Joe and acting alcalde of Béxar, Francisco Antonio Ruíz, both of whom were asked to identify Travis’s body. Ruíz said Travis lay on or by a gun carriage stationed on the north wall, “shot only in the forehead.” Joe testified Travis was shot in the head on the north wall, atop a cannon rampart.10 De la Peña also wrote, “all of the enemy perished, there remaining alive only an elderly lady and a Negro slave.” Whether de la Peña’s description referred to Joe and Susanna Dickinson, wife of Captain Almaron Dickinson, isn’t clear, but it’s generally accepted that at least fourteen (maybe more) survived the assault.11

Concerning Crockett’s death: The brief description in de la Peña’s “diary” is contained on a single slip of paper—the verso of folio 35—written on a different kind of paper from the rest of the “diary” (consisting of 105 folded “quartos” of four pages each) and in a different hand.12 Folio 35 was tucked into the manuscript, as several other slips of paper were, suggesting it was one of several accounts, rumors, and stories collected from other sources and inserted where they chronologically fit, rather than being an authentic de la Peña eyewitness account of the events of March 6, 1836. This is troublesome. But beyond this, de la Peña didn’t mention the execution of Crockett in his 1839 pamphlet—Una Victima del Despotismo (A Victim of Despotism)—which discusses the execution of “a few unfortunates,” including “a man who pertained to the natural science.” Somehow this unnamed man in the pamphlet becomes “the naturalist David Crockett” in the “diary.” And yet, de la Peña doesn’t claim to be an eyewitness to the executions in his pamphlet. Even more troubling, if you remove the suspected folio 35 from the rewritten diary, the supposed source material for the main narrative, de la Peña did not write about the events of that critical day: March 6. As a matter of fact, the original diary doesn’t contain entries for March 3 through March 7.

Moreover, there is confusion as to what de la Peña (or someone else) actually witnessed, as recorded on folio 35. The account casts General Ramírez y Sesma—whom de la Peña despised, as he makes clear in other places in his narrative—as the villain who ran Crockett through with his saber or hacked the frontiersman to death. And yet, de la Peña says he “will not bear witness to this, for though present, I turned away horrified in order not to witness such a barbarous scene.” Which is it? Did he witness the execution of Crockett or not? And was Sesma the executioner? It stretches credulity that if this actually happened and de la Peña was present he couldn’t verify the veracity of Crockett’s manner of death and of Sesma’s involvement. Even more, it seems highly unlikely that Sesma was even within the walls of the Alamo at the time since he was in command of the Mexican cavalry outside the fort and was busy overseeing the corralling and killing of some sixty Texians who managed to escape the Alamo.

Mexican and Tejano Testimony That Crockett Died in Battle

The silence of other Mexican reports and the problems with the de la Peña “diary” cast doubt on Crockett being captured or surrendering only to face the wrath of Santa Anna and the blade of a Mexican sword or bayonet. But there’s another reason to doubt the execution theory: testimony of Mexicans and Tejanos who saw Crockett die in battle.

Several Mexican combatants testified that Crockett died during the assault, including Sergeant Felix Nuñez, Captain Rafael Soldana, and an another, though unidentified, captain. And then there’s the testimony of Madame Candelaria—María Andrea Castañón de Villanueva—who claimed “she was nursing Colonel James Bowie who was in bed very ill of typhoid fever.” She said of Crockett, who had dined at her home before the siege and final battle, that he was “one of the strangest-looking men I ever saw. He had the face of a woman and his manner was that of a young girl. I could not regard him a hero until I saw him die.” She asserted he died with “a heap of dead Mexicans at his feet,” outside Bowie’s door in an attempt to protect Bowie.13

Identifying the Body of Crockett

The most compelling and striking evidence against the execution theory is the fact that two men who knew Crockett by sight—Joe and Ruíz—were asked by Santa Anna to identify the frontiersman’s body. Both did so. If Crockett had come before Santa Anna as a prisoner, only to be put to death on the General’s order, why would he need others to identify Crockett?

Susanna Dickinson, in her earliest account said, “[Crockett] and his companions were found surrounded by piles of assailants.” Forty years later, she told James Morphis, “I recognized Col. Crockett lying dead and mutilated between the church and the two story barrack building, and even remembering seeing his peculiar cap laying by his side.”14 Joe, who left the Alamo with Mrs. Dickinson, added that Crockett’s body was found among the bodies of a few of his friends and twenty-four dead Mexican soliders.15 Six years after the fall of the Alamo, in a lecture by Reverend James Hazard Perry, who was present at the battle of San Jacinto, recounted a story Joe supposedly told him about the death of Crockett.

He continue to cheer on his companion till they were reduced to seven. Being then called on to yield, he shouted forth defiance, leaped into the crowd below, and rushed towards the city. Being pursued by two soldiers, he kept both at bay for a time, until he was finally thrust through by a lance.16

A shout of defiance and a leap into the melee doesn’t sound like a man intending on surrendering. Later Joe is quoted as saying, “One man alone was found alive when the Mexicans had gained full possession of the fort; he was immediately shot by order of the Mexican chief.”17 If this man had been as well known as Crockett, whom Joe knew, you would think he would have said so. He didn’t.

Another eyewitness to the battle was eleven-year-old Enrique Esparza, whose father, Gregorio, died with Crockett, Travis, Bowie, and the other Alamo heroes on that Sunday morning. Enrique placed Crockett’s body in front of the church’s large double doors, surrounded by a heap of dead soldados. And Ben, servant to Mexican Colonel Almonte, said there were “No less than 16 dead Mexicans around the corpse of Colonel Crockett, and one across it with the huge knife of Davy buried in the Mexican’s bosom to the hilt.”

Historian James Donovan places Crockett’s body in the western lunette. He writes,

The honorable David Crockett was located with some of the other Tennessee men in the small lunette midway down the west wall, the bodies of several soldados scattered around them. Crockett’s coat and rough woolen shirt were soaked with blood—either a musket ball or a bayonet had ripped into his chest. He had sold his life dearly, dying in the open air, as he wished—and, as he put it in the final words of his last letter, “among friends.”18

Reuben Potter, an early Alamo researcher, agreed that Crockett’s corpse was located in the area of the lunette. According to interviews conducted with Mexican soldiers who participated in the assault, “Crockett’s body was found, not in an angle of the fort, but in a one-gun battery with overtopped center of the west wall, where his remains were identified by Mr. Ruíz, a citizen of San Antonio, whom Santa Anna, immediately after the action, sent for and ordered to point out the slain leaders of the garrison.”19 Two years later, Potter wrote the editors of The Century correcting some facts about Crockett’s death the magazine got wrong in a piece about Sam Houston. The editors published this correction: “Captain Ruben M. Potter, U.S.A., writing to correct some statements in an account of the fall of the Alamo . . . states that Crockett was killed by a bullet shot while at his post on the outworks of the fort, and was one of the first to fall.”20

The placement of Crockett’s body isn’t settled history, as these accounts attest—though I believe the most likely area was in or around the western lunette. Nevertheless, none of these statements indicate Crockett was captured or surrendered to be put to death on Santa Anna’s order. The only reasonable conclusion is to judge the “evidence” and arguments in support of the execution theory as failing to meet the demands of historic fact. When the guns died and the smoke cleared, Crockett may have surrendered or been captured and put to the sword, but until better evidence and stronger arguments come to light, let history show that David Crockett died fighting “among friends”—his fellow Texians.

Notes:

1 Crockett biographer Michael Wallis includes a humorous list of “implausible and ludicrous” conspiracies theories about Crockett surviving the final assault at the Alamo. See David Crockett: The Lion of the West (New York: W. W. Norton, 2011), 300–301.

2 “Sam Houston to J. W. Fannin, Commanding at Goliad,” March 11, 1836, in 100 Days in Texas: The Alamo Letters, ed. Wallace O. Chariton (Plano: Wordware Publishing, 1990), 358–9.

3 See The Alamo Reader: A Study in History, ed. Todd Hansen (Mechanicsburg: Stockpile Books, 2003), 730.

4 José Enrique de la Peña, With Santa Anna in Texas: A Personal Narrative of the Revolution, trans. Carmen Perry, expanded edition (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1997), 52, 53–54.

5 William C. Davis, Three Roads to the Alamo: The Lives and Fortunes of David Crockett, James Bowie, and William Barret Travis (New York: HarperCollins, 1998), 737n.

6 See for example Stephen L. Hardin, Texas Iliad: A Military History of the Texas Revolution (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994); James E. Crips, Sleuthing the Alamo: Davy Crockett’s Last Stand and Other Mysteries of the Texas Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005); Dan Kilgore and James E. Crips, How Did Davy Die? And Why Do We Care So Much? (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2010); Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and Jason Stanford, Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth (New York: Penguin Press, 2021).

7 Joseph H. Barnard, June 9, 1836, in James Donovan, The Blood of Heroes: The 13-Day Struggle for the Alamo—and the Sacrifice That Forged a Nation (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2012), 441n.

8 Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes in this and the following sections are from Donovan, 446–453n.

9 William C. Davis, “How Davy Probably Didn’t Die, Journal of the Alamo Battlefield Association, vol. 2, no. 1 (Fall 1997).

10 Joe later testified that the gunshot to Travis’s head wasn’t immediately fatal. A Mexican officer, whom Joe identified as Colonel Esteban Mora, seeing Travis alive rushed at him with a drawn sword. Travis, however, was able to thrust his sword into Mora’s body before dying. See Ron J. Jackson Jr. and Lee Spencer White, Joe: The Slave Who Became an Alamo Legend (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015), 191, 238. This story is highly suspicious, if for no other reason than the standard Mexican infantry musket, the 0.753 caliber Brown Bess, fired a ball a half inch in diameter. If the shot wasn’t fatal, it had to be a glancing shot, which seems unlikely since Travis was shot in the forehead.

11 Known survivors include Susanna Dickinson, Angelina Dickinson (daughter), Joe, Mrs. Horatio Alexander Alsbury (Juana Navarro Alsbury) and her baby boy, her sister Gertrudis Navarro, Mrs. Gregorio Esparza and her four children, Trinidad Saucedo, Petra Gonzales, and Brigido Guerrero, who claimed to have been a prisoner of the Texians and was set free by Santa Anna. See Hansen, 730–31, who claims there’s strong evidence that Henry Warnell lived through the assault, escaped, and died of wounds sustained three months later.

12 You would never know this by reading the English translation, and presumably the original Spanish manuscript, since it’s presented as a unified whole.

13 Bill Groneman, Eyewitness to the Alamo, revised edition (Lanham: Republic of Texas Press, 2001), 137. Hansen (731) asserts that Madam Candelaria “definitely was not in the Alamo.”

14 James M. Morphis, History of Texas from Its Discovery and Settlement (New York: United States Publishing Company, 1874), 177.

15 William Fairfax Gray, From Virginia to Texas, 1835: Diary of Col. Wm. F. Gray, Giving Details of His Journey to Texas and Return in 1835–1836 and Second Journey to Texas in 1837 (Houston: Gray, Dillaye & Co., 1909), 137.

16 J. H. Perry, “Lecture on Texas,” New-York Lyceum, New York, New York, November 23, 1842, quoted in the New-York Daily Tribune, November 24, 1842, column 5, page 2.

17 John M. Niles, A History of South America and Mexico (Hartford: H. Huntington Jr., 1838), 327.

18 Donovan, 292; Robert L. Durham agrees that Crockett probably fell in the small semicircle lunette along the western wall. See “Where Did Davy Die?” Alamo Anthology: From the Pages of The Alamo Journal, ed. William R. Chemerka (Fort Worth: Eakin Press, 2005), 110.

19 Reuben Potter, Magazine of American History, February 1884, 177, in Donovan, 444n.

20 The Century, October 1886, in Donovan, 444n.

The piece you just read was 1836% pure Texas. If you enjoyed it I hope you’ll share it with your Texas-loving friends to let them know about Y’allogy.

As a one-horse operation, I depend on faithful and generous readers like you to support my endeavor to keep the people, places, and past of Texas alive. Consider becoming a subscriber today. As a thank you, I’ll send you a free gift.

Find more Texas related topics on my Twitter page and a bit more about me on my website.

Dios y Tejas.

See "Death of Legend - the Myth and Mystery Surrounding the Death of Davy Crockett."

Growing up in Texas and attending public school here, we were taught Davy's Crockett's motto: "First make sure you are right, then go ahead". It is a good motto. It speaks to having the humility to consider the fact that you may not be right and that maybe you should not act unless you are likely right about whatever you are acting upon. It also requires what we used to call 'gumption', which is a word I see used differently by people who do not seem to be from Texas.

As I was taught, gumption is the correct mixture of good judgment and assertiveness, so that one can be sure your actions are in the right. Do not be a coward, but do not be foolhardy either. Fools who do not ascertain the facts first end up getting people killed.