Naming the Alamo Dead

“Good name in man and women, dear my lord, / Is the immediate jewel of their souls.”

William Shakespeare, “Othello”

Texas is my rooting ground, so I can’t speak for other places, but in the Lone Star state history is a contact sport—sometimes devolving into a blood sport. Recently, the official Twitter account for the Alamo posted a picture of a young boy dressed in a Crockett costume. One respondent challenged the implication that the folks at the Alamo primarily (if not exclusively) champion the Anglo narrative of what happen there in late February and early March of 1836, to the exclusion of the Hispanic narrative. He decried the “indoctrination” of the coon-skinned clad lad and accused the Alamo historians of a “bias against a more balanced take on history and lack of openness to a more educated portrayal of History.”

The official Alamo’s response was to block him.

Another respondent questioned why Crockett should be more celebrated than the Tejanos who died fighting at Crockett’s side. After all, this gentleman pointed out, Crockett had only been in Texas for two months before his death at the Alamo. When I read this comment I thought, He has a point. I wrote in an earlier piece—“Juan Seguín Buries the Hero Dead of the Alamo”—

It is an unfortunate and inexcusable fact that the heroism of the Tejanos during the Texas Revolution have received so little recognition and praise. It is highly doubtful that without their determination, courage, and sacrifice—known and unknown—Texas would have ever become an independent republic.

But then I thought, Crockett was famous long before he crossed the Sabine River in January 1836. His frontier exploits were the stuff of legend—at least according to the dime novels and plays written about him. As a congressman (and possible presidential candidate), Crockett distinguished himself as a courageous defender of native Americans, particularly in his opposition to President Andrew Jackson’s Indian removal bill—the passage of which resulted in the Trail of Tears. Crockett’s notoriety grew with his famous rhetorical flourish after losing reelection in 1835, telling his former constituents: “You may go to hell, and I will go to Texas.”

But to get back to the point of whether Crockett is more deserving of celebration than the Tejanos who died on March 6, 1836: he isn’t. If it seems he is, it’s become his name is widely known and theirs aren’t. Even at the time, the victorious Antonio López de Santa Anna asked to be shown Crockett’s body. The same cannot be said for any of the Tejanos (nor Anglos) who died with David Crockett, William Travis, and James Bowie—the only other Anglo defenders most folks could readily name.

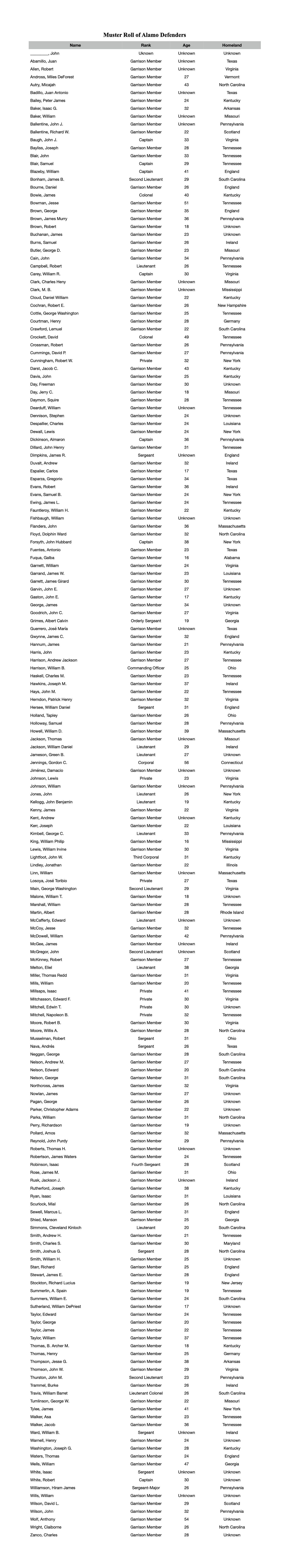

The fact that Crockett, Travis, and Bowie are well known doesn’t make their sacrifice more noble than the sacrifice made by the other 186 men who fell that day. And though historians over the intervening period, nearly two centuries now, have struggled to compile a definitive list of Alamo defenders, all of them have taken care to honor each man by identifying and naming each one.*

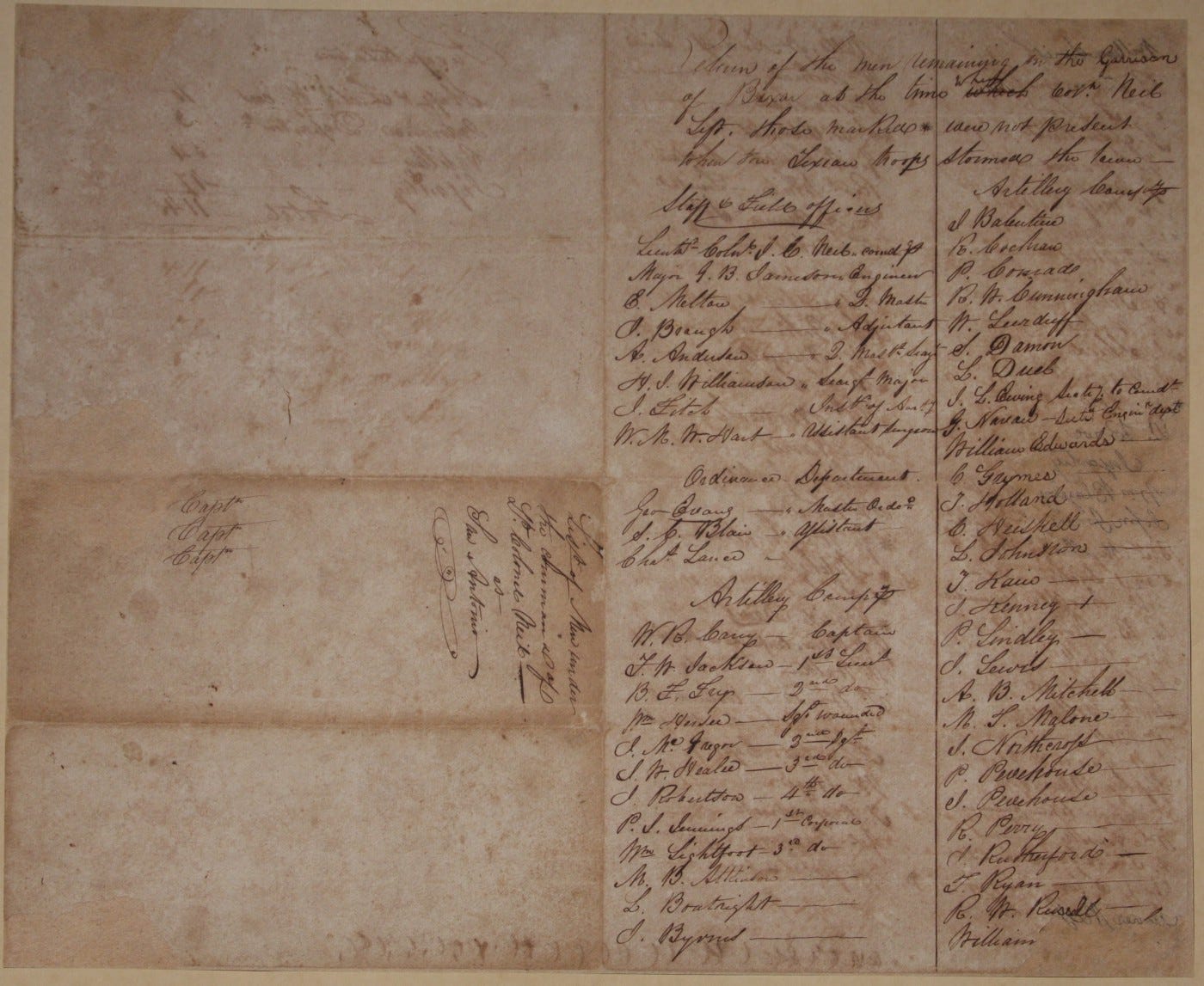

The trouble in creating an authoritative list comes from a number of factors. The the Alamo’s garrison was in a state of flux from the time Lieutenant Colonel James C. Neill took command in December 1835, to his departure in February 1836, and up until the final assault on March 6. Couriers came and went practically throughout the thirteen-day siege, including many Tejanos under the command of Juan Seguín. And some volunteers entered the Alamo as late as March 4, two days before the decisive battle. Compounding the difficulty in nailing down an undisputed list is the fact that a muster roll on or around the garrison’s final day does not exist. If Travis had written one it was either taken by a Mexican solider (and has yet to surface) or was destroyed in the final attack or when Santa Anna had the bodies burned. The best we can do is reconstruct the names of the garrison from muster roles from the Alamo prior to the battle, during Neill’s command, from newspaper reports, first-hand accounts of those who were at coming and going from the Alamo prior to March 6, as well as the testimony of the women, children, and slaves, like Joe, who survived the predawn assault, and from land grants claimed by descendants of Alamo defenders.

The current “official” list from the Alamo places the number of defenders at 189, hailing from the United States, Europe, and, of course, Texas. Here are their names, ranks, ages, and homelands.

Howdy, folks. If you’re reading this from a post off social media, or a friend shared this with you, welcome. Pull up a chair, put your boots up, and stay awhile—and consider becoming a subscriber. If you’re already a subscriber, and like what you read, think about becoming a partner to keep Y’allogy going and growing by upgrading as a paid subscriber. But whatever y’all choose to do, I’m much obliged y’all are here.

By naming the dead, we, with Juan Seguín, “honor . . . the valiant heroes who died in the Alamo.”

* On my last visit I was disappointed to see gentleman and boys were no longer required to remove their hats or ball caps while walking through the chapel. It is my sincere hope this requirement be reinstated and enforced. Regardless of what one thinks about those who died at the Alamo, the dead deserve more respect—Anglo, Tejano, and Mexican alike.