Lone Star Characters: Elizabeth "Lizzie" Johnson Williams

Y’allogy is an 1836 percent purebred, open-range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is free of charge, but I’d be grateful if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber.

There can be no denying that she was not only a gallant frontier Texas woman in the cattle trade but also a pioneer among women in the field of finance—a character so colorful and varied that she has become almost a legend.

Emily Jones Shelton

At the tail end of the Great Depression, in the late 1930s, Ruby Mosley, a writer with the Federal Writers’ Project arrived in San Angelo, Texas to interview Mrs. Ben McCulloch Earl Van Dorn Miskimon.1 During the interview, Mrs. Miskimon said, “My husband was no cowman; I tried to teach him about cows, but he never could learn, not even to feed one. . . . I was pretty much of a businesswoman, as well as a cowpuncher.”

If she had lived longer, or Ruby Mosley had lived earlier and interviewed her, Elizabeth Johnson Williams could have said the same of her husband Hezekiah.

Elizabeth Johnson—Lizzie, as she was called—was born in Missouri in 1843, the second of six children of professor Thomas Jefferson Johnson—“Old Bristle Top”—and Catherine Hyde Johnson. Her family moved to Texas in the latter half of the 1840s to work as missionaries, preaching the gospel to folks whom Stephen F. Austin said had “all the licentiousness and wild turbulence of frontiersmen.” But Thomas, a strict Presbyterian, wasn’t put off by the rawness of the frontier. Within a few years, in 1852, he had established the Johnson Institute in Hays County—the first school of higher learning west of the Colorado River, where you could enter in the first grade and graduate with the equivalent of a Bachelor of Arts degree. He had been offered the original forty acres where the University of Texas would be built, but turned it down because the city of Austin allowed liquor within city limits. Instead, he chose a site seventeen miles southwest of Austin and some thirty miles north of San Marcos.

When Lizzie turned sixteen, she began teaching at the co-ed Institute, earning a reputation as an austere and stern teacher. Like her father, she was a devoted Christian and brooked no rebellion among her pupils. Her subjects included French, arithmetic, bookkeeping, spelling, and music, which she taught on piano—the first in Hays County.

Lizzie left the Institute after a time to teach in Manor, Lockhart, and Austin. She also began writing, earning a tidy sum through the years by submitting stories for newspapers and periodicals like the Frank Leslie Magazine. In what would become a familiar trait, she kept her writing a secret, publishing under a pen name. What she did with her money also became a familiar trait: she invested it. A couple of years after her death in 1924, the Austin-American Statesmen gave readers an idea of her business acumen: “At one time she bought $2,500 worth of stock in the Evans, Snider, Bewell Cattle Company in Chicago; this paid her 100 per cent dividends for three years straight, and she sold it at the crucial time for $20,000.”

Lizzie’s timing was fortuitous. In 1871, when she entered the cattle business, the beef boom was booming. During the Civil War, with men away fighting in the east and unable to tend their herds, cattle roamed freely throughout Texas—unclaimed and unbranded. Estimates indicate the cattle population increased nearly twenty-five percent every year between 1861 and 1864. But even if men had been available there was no market for Texas beef during those years, not even in the Confederacy because of Union blockades of Texas ports and their control of the Mississippi River. As a result, the value of Texas beef fell precipitously. There was more value in the hides and tallow of longhorns than in the meat, leading to the slaughter of thousands in what became known as the “skinning war.” Carcasses became carrion—food for buzzards and coyotes.

In the Union north the situation was exactly the opposite. Demand for beef was high, but there was little to no supply. At war’s end, in 1865, the value of beef in the North was ten times as much as it was in Texas. With men returning to the cattle rich state enterprising ranchers and investors began rounding up unclaimed animals—mavericks—and slapped their brands on them. This was especially true in the brush country of southwest Texas, where brush poppers flushed hidden cattle from the underbrush. Lizzie took advantage of this free-for-all by rounding up free cattle to sell in northern markets, registering her CY brand and ear marks in the Travis County Record Book on June 1, 1871. She was twenty-eight and unmarried.

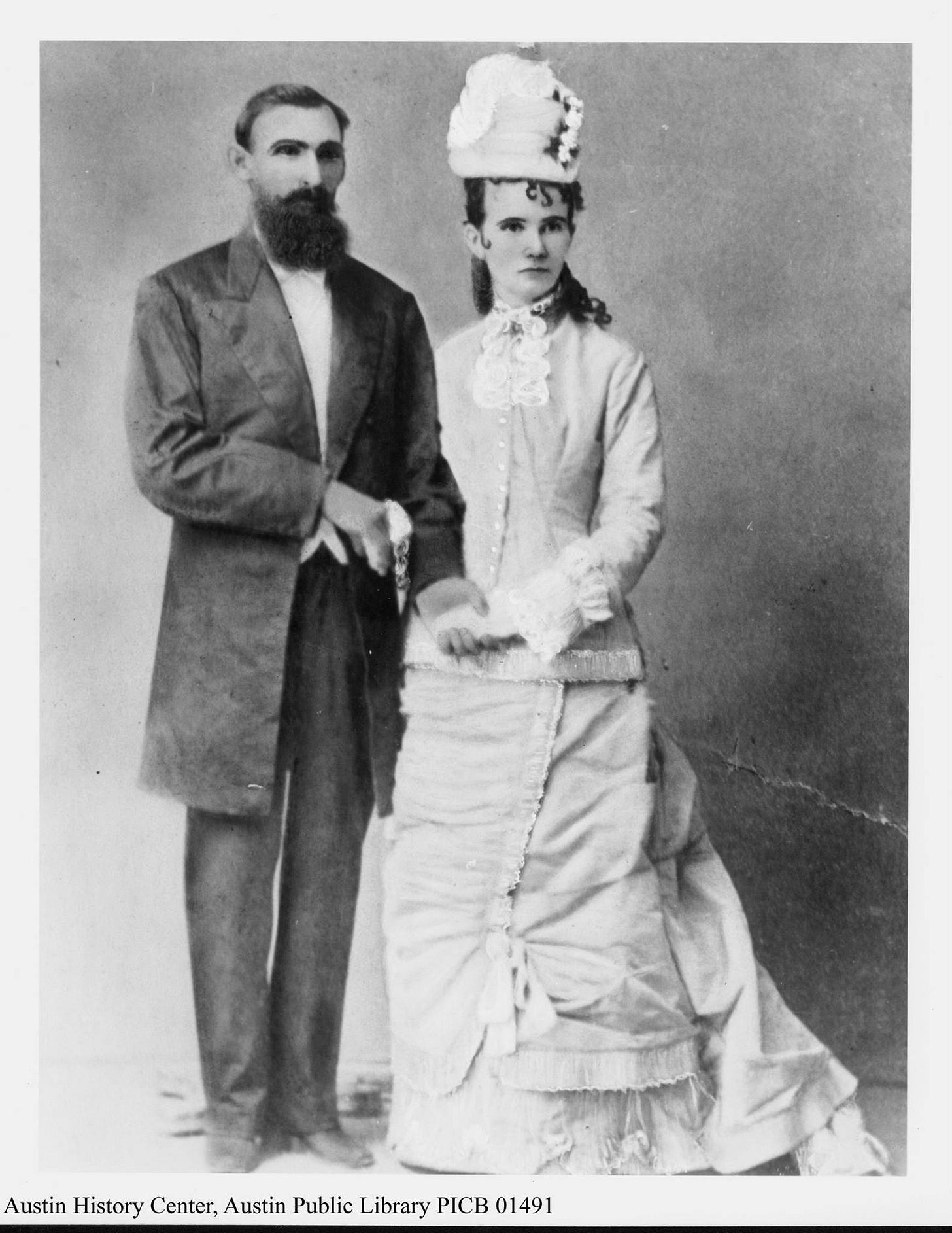

Eight years later, on June 8, 1879, at the age of thirty-six, Lizzie married Hezekiah G. Williams, a preacher and widower with several children. They lived in Austin in a two-story home. Along with her cattle business and publishing pursuits, Lizzie continued to teach, operating a private school in the downstairs portion of her home, while the family lived in the four rooms upstairs.

Before Lizzie agreed to marry Hezekiah she made him sign a prenuptial agreement stating that all her property remained hers and that all future profits produced by her business dealings were hers alone. This was not only well ahead of its time, it also proved wise since Hezekiah, who entered the cattle business in 1881, as the boom was busting, was a poor businessman. She often bailed him out of foolish deals after he had been taken in by unscrupulous bankers. While in Cuba, Hezekiah was kidnapped. The bandits demanded a $50,000 ransom. Lizzie paid it and made Hezekiah pay her back to the penny. She wasn’t about to lose a dime on a foolish husband, even though she was, as was said, “devoted to him to the point of idolatry.”

Hezekiah’s foolish business practices were paired with unethical business practices, if his brother-in-law Will is to be believed. Hezekiah’s profession as a preacher notwithstanding, Will often joked, “While Hezekiah was preaching on Sunday, his sons were out stealing his congregation’s cattle.”

Whether that’s true or not, what is true is that Lizzie and Hezekiah were business competitors. They often bought cattle at the same time, but Lizzie always instructed her cowboys to pick the best ones for her herd. They both used the same foreman and gave him the same instructions: to roundup unbranded calves from the the other’s heard and brand them as their own.

Once branding was done, it was time to drive their herds to market. Hezekiah and Lizzie both went up the Chisholm Trail.2 Though together, their respective herds and cowboys were independent of each other. They rode together behind their respective herds and chuck wagons in a buggy drawn by a team of horses. It’s believed Lizzie was the first woman to drive her own herd with her own brand up the Chisholm.

Driving cattle up any trail, including the Chisholm, was a dangerous undertaking, one that “tested the courage and endurance of sturdy men, and was considered entirely too dangerous to be undertaken by a woman,” as Mary Taylor Bunton, who also went up the trail, put it. Drovers could expect heat and dust, thunderstorms and hail, flooded rivers, and hundreds of miles of featureless grasslands through Indian territory. There was no assurance of reaching trail’s end with your herd or yourself intact. Cattle could be rustled or stampeded, horses could throw a man by bucking or pitching him by stepping in a gopher hole. Grub consisted of a coarse diet of sourdough biscuits, sonofabitch stew, and beans.

None of that deterred Lizzie. She thrived in the cattle business.

She also thrived in real estate, owning properties in Austin and in Llano, Hays, and Trinity counties. She own small ranches in Culbertson and Jeff Davis counties, as well as the Williams Ranch of several thousand acres co-owned with Hezekiah near Driftwood in Hays and Blanco counties.3

In 1914, after thirty-five years of marriage, Hezekiah died in El Paso. Lizzie had his body brought back to Austin, where she buried him in a six hundred dollar casket, writing across the bill of sale: “I loved this old buzzard this much.” After Hezekiah’s death, Lizzie continued to increase her business holdings, founding and presiding over the American National Bank in Austin.

Her latter years were Howard Hughes-like. She became a recluse, an eccentric, and a miser. Despite her wealth, she allowed herself no luxuries and few necessities. Late in her seventies, her grandnephew Emmitt Shelton visited her Austin home. Seeing nothing to eat in the house, Emmitt offered to get dinner for her. She refused. She said she had plenty to eat. “Where?” Lizzie picked up an old tin typewriter cover from a near-by table and revealed a small piece of cheese and a few crackers. The cover was to keep the rats from running off with her meal. Emmitt later said,

We knew she was starving to death, but I had children and could not get down to take food to her every day. None of the rest of her family knew much about her. . . . Finally, a restaurant owner, renting her building, would send dinners up to her every day. She thought he was the nicest man because she thought the dinners were free. She never knew that we paid for them.

She was so tightfisted she only burned one stick of firewood at a time, even in the depths of winter—a practice she applied to her downtown Austin tenants. Wood was stockpiled in a locked room and issued stick by stick, even though her woodpile included five hundred neatly stacked pieces.

Lizzie lived ten years after Hezekiah’s death, passing away on October 9, 1924, in Austin. Going through her possessions at the Brueggerhoff Building, which she owned, Lizzie’s family found $2,800 tucked away here and there, and a fortune in diamonds locked way in a box in the basement, which also contained parrot feathers (from a bird picked up in Cuba) and dried flowers from Hezekiah’s funeral wreaths. In total, her net worth was somewhere between $188,000 and $220,000. Her net worth today would amount to $3.4 million to $4.0 million.

She is buried next Hezekiah at Oakwood Cemetery in Austin.

“There can be no denying that she was not only a gallant frontier Texas woman in the cattle trade,” her biographer wrote, “but also a pioneer among women in the field of finance—a character so colorful and varied that she has become almost a legend.”

1 The Federal Writers’ Project was a relief organization associated with the Work Projects Administration that provided federal jobs to white-collar workers (writer, editors, researchers, and journalists) during the Great Depression. Members of the TFW were tasked with compiling information in a guide book to the United States. As the project grew, each state was tasked with publishing its own guide book, filled with facts and lore. The FWP of Texas published Texas: A Guide to the Lone Star State in 1940.

2 The exact year when Lizzie and Hezekiah went up the Chisholm Trail is unknown, but it must have been sometime between 1881 (after she married Hezekiah and he got into the cattle business) and 1889 (when the Chisholm Trail passed out of use). Regardless, it was unusual for women to drive a herd of cattle up any trail. Other women known to do so includes Amanda Burks—“Queen of the Trail Drivers”—who in 1870 pushed cattle up the Chisholm Trail with her husband W. F. Burks, and Mary Taylor Bunton, a bride who went up the trail with her husband in 1886.

3 In time, Hays City would be built on the Williams Ranch.

Mrs. Ben Miskimon, interview by Ruby Mosley, in Texas Cowboys: Memories of the Early Days, ed. Jim and Judy Lanning (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1984), 200, 202.

Emily Jones Shelton, “Lizzie E. Johnson: A Cattle Queen of Texas,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, vol. 50, no. 3 (January 1947), 349–366.

The 1836 Percent Y’allogy Guarantee: This newsletter is created by a living, breathing Texan—for Texans and lovers of Texas. It exists thanks to the generosity of its readers. To ensure it continues, I invite you, if you’re able and haven’t already done so, to ride for the brand as a paid subscriber, give the gift of Y'allogy to a fellow Texan, or purchase my novel.

Much obliged, y’all.

Do you have a map? I'd love to look at the various spots mentioned, especially Hays City, since I'm a Hays County girl.

I enjoy your old stories about old times and brave people