José de Urrea's Goliad Lament

It was painful to me . . . that so many brave men should thus be sacrificed, particularly the much esteemed and fearless [James W.] Fannin. –José de Urrea

Y’allogy is 1836 percent pure bred, open range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is free of charge, but I’d be much obliged if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber. (Annual subscribers of $50 receive, upon request, a special gift: an autographed copy of my literary western, Blood Touching Blood.)

The fight for independence that took place in the northern Mexican state of Tejas in 1835 and 1836 resulted in the creation of the Republic of Texas—an independent nation dominated by English-speaking citizens. They were the ones who predominately shaped the political contours of Texas’ new government and wrote the histories of the revolution. But Anglo Texians—as they called themselves—weren’t the only players in the Republic’s drama. Tejanos—native Texans from Hispanic descent—also played an important role in that drama: men like José Antonio Navarro and José Francisco Ruiz, signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence, Lorenzo de Zavala, another signer and first vice president of the Republic, and Juan Seguín, who fought with Sam Houston at the battle of San Jacinto.

When it comes to the study of Texas history most students hear very little about these men—and nothing of the Mexican perspective of the Texas Revolution. That’s a shame. There is much to be learned from looking at this period from the other end of the musket. Generally speaking, Anglo Texans throughout the nearly two centuries of Texas history, independent of Mexico, have viewed Tejanos with a jaundiced eye and the Mexicans who crossed the Rio Grande with General Antonio López de Santa Anna as no better than butchers.

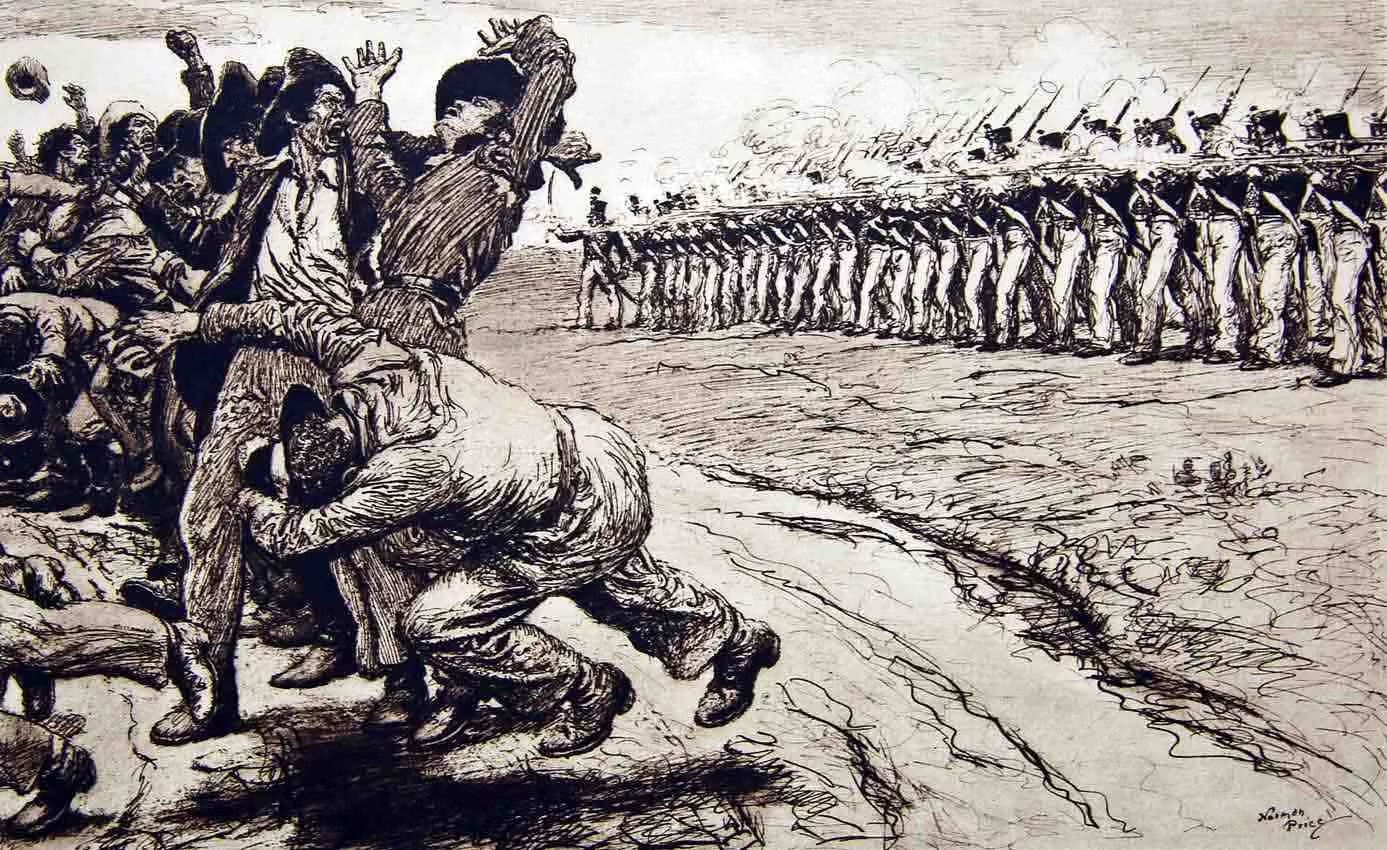

The image of Mexicans as blood-hungry savages became well established when stories spread throughout Texas of what took place within the walls of the Alamo, when the few surviving defenders attempted to surrender and were summarily put to the sword and bayonet. The image became indelibly stained on the Texian mind following Mexican atrocities on the plains outside Presidio la Bahía, when three hundred and forty-two men were executed on Santa Anna’s order. Both events are historical fact. There’s no denying it. But the image of the Mexican butcher applied to every soldado is spreading the butter too thin. There were Mexican officers who didn’t have the stomach for such bloodletting. This was also true of any number of soldados.

At the Alamo, José Enrique de la Peña, who was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Mexican army, expressed his disgust of Santa Anna’s order to execute Alamo survivors. In With Santa Anna in Texas, de la Peña called the order “base murder.” General Manuel Fernandez Castrillón concurred, pleading for the lives of the survivors.

When it came to the massacre at Goliad, which is exactly what it was, the man who actually carried out Santa Anna’s order,1 Colonel José Nicolás de la Portilla, wrote, “There was a great contrast in the feelings of the officers and the men. Silence prevailed,” indicating that fulfilling this order was distasteful. Of the officers who clearly viewed Santa Anna’s order as distasteful was Colonel Francisco Garay, who along with Francita Alavez—the “Angel of Goliad”—saved Major William Parsons’s Nashville Battalion, which was captured at Copano on March 20, 1836, and marched to Goliad.

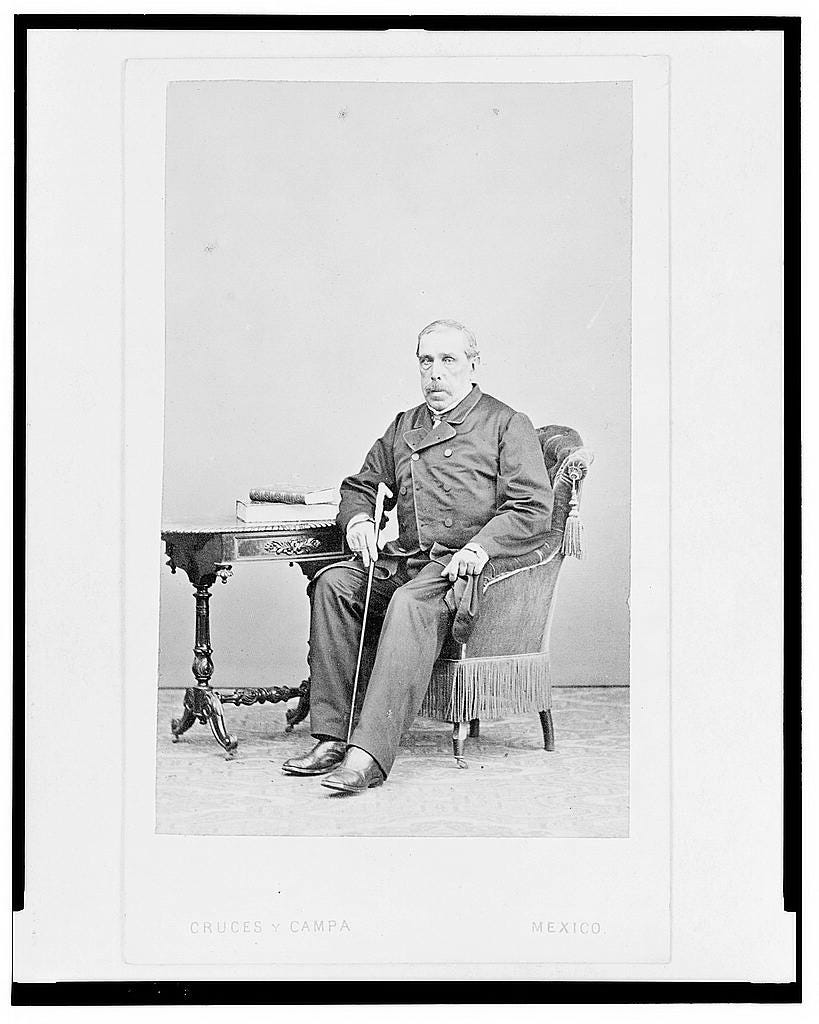

And then there was General José de Urrea, the commander of the troops holding the prisoners at Goliad. He recorded in his diary that the order was a “barbarous and inhuman decree.” Here’s his account of what transpired leading up to the massacre on March 27, 1836—Palm Sunday.

[March 22, 1836] I will proceed with my diary. The active battalions of Querétaro and Tres Villas arrived in Goliad to-day and brought a twelve-pounder.

23. I returned to Victoria with the prisoners taken with [William] Ward [who surrendered on March 22] and received news at this place that eighty-two men had surrendered at Cópano with all their arms and munitions. I sent scouts to Lavaca Lake and the stream bearing the same name, as well as to that of La Navidad. I dictated ten orders for the security of Cópano and the prisoners at Goliad, the establishment of hospitals, and the rebuilding of the fort there by the prisoners, excusing from this work only those who were officers. I gave instructions also for all the forces with which I was to continue the campaign to join me, bringing the artillery and corresponding ammunition. Among the instructions given on this day I ordered that a thorough investigation be undertaken to determine the views and principal aims that moved the officers who are our prisoners to take up arms. The finding of this investigation are among my papers.

I spent the 24th, 25th, 26th, and 27th in organizing my forces, equipment, and ammunition, and in drawing up many instructions for the security of the military posts that I was leaving on our rear, as well as for the better care of the wounded who have been up to now in the hands of a bad surgeon. As among the prisoners there were man skilled in all trades, I secured surgeons from among them who were very useful to us as well as to the sick in the hospital at [San Antonio de] Béxar, where I sent those that were needed.

On the 25th I sent Ward and his companions to Goliad. The active battalion of Querétaro joined me on the 26th. On the 27th, between nine and ten in the morning, I received a communication from Lieut. Col. Portilla, military commandant of that point, telling me that he had received orders from His Excellency, the general-in-chief [Antonio López de Santa Anna], to shoot all the prisoners and that he was making preparations to fulfill the order.

This order was received by Portilla at seven in the evening of the 26th, and although he notified me of the fact on the same date, his communication did not reach me until after the execution had been carried out. All the members of my division were distressed to hear this news, and I no less, being as sensitive as my companions who will bear testimony of my excessive grief. Let a single one of them deny this fact! More than 150 prisoners who were with me escaped this terrible fate; also those who surrendered at Cópano and the surgeons and hospital attendants were spared. Those which I kept, were very useful to me as sappers.

I have come to an incident that has attracted the attention of foreigners and nationals more than any other for which there have not been lacking those who would hold me responsible, although my conduct in the affair was straightforward and unequivocal. The orders of the general-in-chief with regard to the fate decreed for prisoners were very emphatic. These orders always seems to me harsh, but they were the inevitable result of the barbarous and inhuman decree which declared outlaws those whom it wished to convert into citizens of the republic. Strange inconsistency in keeping with the confusion that characterized the times!

I wished to elude those orders as far as possible without compromising my personal responsibility; and, with this object in view, I issued several orders to Lieut. Col. Portilla, instructing him to use the prisoners for the rebuilding of Goliad. From this time on, I decided to increase the number of the prisoners there in the hope that their very number would save them, for I never thought that the horrible spectacle of that massacre could take place in cold blood and without immediate urgency, a deed proscribed by the laws of war and condemned by the civilization of our country. It was painful to me, also, that so many brave men should thus be sacrificed, particularly the much esteemed and fearless [James W.] Fannin [the Texian commander at Goliad]. They doubtlessly surrendered confident that Mexican generosity would not make their surrender useless, for under any other circumstances they would have sold their lives dearly, fighting to the last. I had due regard for the motives that induce them to surrender, and for this reason I used my influence with the general-in-chief to save them, if possible, from being butchered, particularly Fannin. I obtained from His Excellency only a severe reply, repeating his previous order, doubtlessly dictated by cruel necessity. Fearing, no doubt, that I might compromise him with my disobedience and expose him to the accusation of his enemies, he transmitted his instructions directly to the commandant at Goliad, inserting a copy of the order to me. What was done by the commandant is told in his diary.2 Here, as well as in his communication, are seen the motive that made him act and the anguish which the situation caused him. Even after this lamentable event, I still received a letter of the general-in-chief, dated on the 26th, saying: “I say nothing regarding the prisoners, for I have already stated what their fate shall be when taken with arms in their hands.”

In view of the facts presented, and keeping in mind that while that tragic scene was being enacted in Goliad I was in Guadalupe Victoria, where I received news of it several hours after the execution, what could I do to prevent it, especially if the orders were transmitted directly to that place? This is to demand the impossible, and had I been in a position to disregard the order it would have been a violent act of insubordination.

If they wish to argue that it was in my hand to have guaranteed the lives of those unfortunates by granting them a capitulation when they surrendered at Perdido [Creek], I will reply that it was not in my power to do it, that it was not honorable, either to the arms of the nation or to myself, to have done so. Had I granted them terms, I would then have laid myself open to a trial by a council of war, for my force being superior to that of the enemy on the 20th and my position mere advantageous, I could not admit any proposals expect a surrender at discretion, my duty being to continue fighting, leaving the outcome to fate. I believe that I acted in accordance with my duty and I could not do otherwise. Those who assert that I offered guarantees to those who surrendered, speak without knowledge of the facts.

1 “I am informed that there have been sent to you by General Urrea two hundred and thirty four prisoners. . . . As the supreme government has ordered that all foreigners taken with arms in their hands, making war upon the nation, shall be treated as pirates, I have been surprised that the circular of the said government has not been fully complied with in this particular. I therefore order that you should give immediate effect to the said ordinance in respect to all those foreigners who have yielded to the force of arms, having had the audacity to come and insult the republic, to devastate with fire and sword, as has been the case in Goliad, causing vast detriment to our citizens, in a word, shedding the precious blood of Mexican citizens, whose only crime has been their fidelity to their country. I trust that, in reply to this, you will inform me that public vengeance has been satisfied by the punishment of such detestable delinquents.”

2 Lieutenant Colonel Portilla wrote in his diary: “March 26. At seven in the evening I received orders from General Santa Anna by special messenger, instructing me to execute at once all prisoners than by force of arms agreeable to the general orders on the subject. (I have the original order in my possession.) I kept the matter secret and no one knew of it except Col. Garay, to whom I communicated the order. At eight o’clock, on the same night, I received a communication from Gen. Urrea by special messenger in which among other things he says, “Treat the prisoners well, especially Fannin. Keep them busy rebuilding the town and erecting a fort. Feed them with the cattle you will receive from Refugio.” What a cruel contrast in these opposite instructions! I spent a restless night.

“March 27. At daybreak, I decided to carry out the orders of the general-in-chief because I considered them superior. I assembled the whole garrison and ordered the prisoners, who were still sleeping, to be awaked. There were 445. (The eighty that had just been taken at Cópano and had, consequently, not borne arms against the government, were set aside.) The prisoners were divided into three groups and each was placed in charge of an adequate guard, the first under Agustin Alcerrica, the second under Capt. Luis Balderas, and the third under Capt. Antonio Ramíez. I gave instructions to these officers to carry out the orders of the supreme government and general-in-chief. This was immediately done. There was a great contrast in the feelings of the officers and the men. Silence prevailed.”

✭ ✭ ✭

José de Urrea, in The Mexican Side of the Revolution, trans. Carlos E. Castañeda (Dallas: P. L. Turner Company, 1928), 233–7, emphasis in original.

✭ ✭ ✭

Support Y’allogy—

Much obliged, y’all.

Heartbreaking actions that sparked a republic and birthed an undying spirit. Very sad but without this Texan would likely have never meant anything today except Mexican.