Giant Love

Texas. Exhilarating, violent, charming, horrible, fascinating, shocking. Texas alive. A giant. –Edna Ferber

Y’allogy is 1836 percent pure bred, open range guide to the people, places, and past of the great Lone Star. We speak Texan here. Y’alloy is free of charge, but I’d be much obliged if you’d consider riding for the brand as a paid subscriber. (Annual subscribers of $50 receive, upon request, a special gift: an autographed copy of my literary western, Blood Touching Blood.)

She was not the first notable American female novelist, but she was, perhaps, the most prolific and celebrated American female novelist in the first half of the twentieth century. She was known for her strong female characters and the social conscience she brought to her stories. Other female novelists had shared similar traits—Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), Willa Cather’s O Pioneers (1913) and My Ántonia (1918), and Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind (1936). None before her and none of her contemporaries, however, had blended so seamlessly the indomitable spirit within female characters along with an unblinking eye at social injustices within the United States as had Edna Ferber.

Though not a historical novelist, Ferber’s most famous novels found inspiration in the everyday people and places she encountered on her travels. So Big (1924), based on the life of Antje Paarlberg and the Dutch farming community of South Holland, Illinois, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1925. Show Boat (1926), which has been turned into a movie musical more than once, came out of a comment from Winthrop Ames about chartering a boat and drifting down waterways to perform in riverside towns. Cimarron (1930) was conceived after a visit to Oklahoma. It wrestles with Native Americans in the wake of the Great Land Rush of what used to be Indian Territory of the late 1880s and early 1890s.

Then there was Giant (1952).

Texas haunted Ferber for years. “Texas of the 1930s and 1940s was constantly leaping out . . . from the pages of books, plays, magazines newspapers,” she wrote. “Motion pictures of Texas background were all cowboys and bang-bang. Texas oil, Texas jokes, Texas money billowed out of the enormous southwest commonwealth. The rest of the United States regarded it with a sort of fond consternation. It was the overgrown spoiled brat. . . . It was the crude uncle who had struck it rich.”

And yet, she couldn’t shake her fascination with the Lone Star state. There was only one thing to do: visit the “spoiled brat” and the “crude uncle.” She wrote, “In a brief interval of semi-idleness and mental vacuity that occurs now and then in the life of all writers I decided to go down and have a look at this southwest phenomenon as one might travel to gaze upon the Grand Canyon. This Texas represented a convulsion of nature, strange, dramatic, stupefying.”

Ferber’s Texas experience was like opening Pandora’s box or rubbing Aladdin’s lamp—the spirits of Texas escaped and couldn’t be put back in the bottle. They haunted and hounded her until she relented and put pen to paper. But the task overwhelmed her. “This assignment I had given myself was as difficult as the state of Texas is enormous and diverse,” she confessed. She tried to excise Texas by ignoring it—putting it behind her and locking it away in a drawer while she gave herself to other pursuits. But the ghost of Texas couldn’t be locked away and wasn’t through with Edna Ferber. “Giant, the novel, was the result of a haunt,” she wrote.

Like any other specter it had to be exorcised by the customary mumbo-jumbo before its victim could be free of it. There is only one method by which a writer can be rid of a haunting subject, no matter how stubbornly resistant. The ghostly nuisance must be trapped and firmly pinned down on paper so that its wails and moans concerning neglect are forever stilled, its clammy touch on the consciousness banished. . . .

Giant, in the guise of Texas, haunted me for a decade or more. I shrank from it, I shuddered to contemplate the grim task of wrestling with this vast subject. Finally I wrote it to be rid of it.

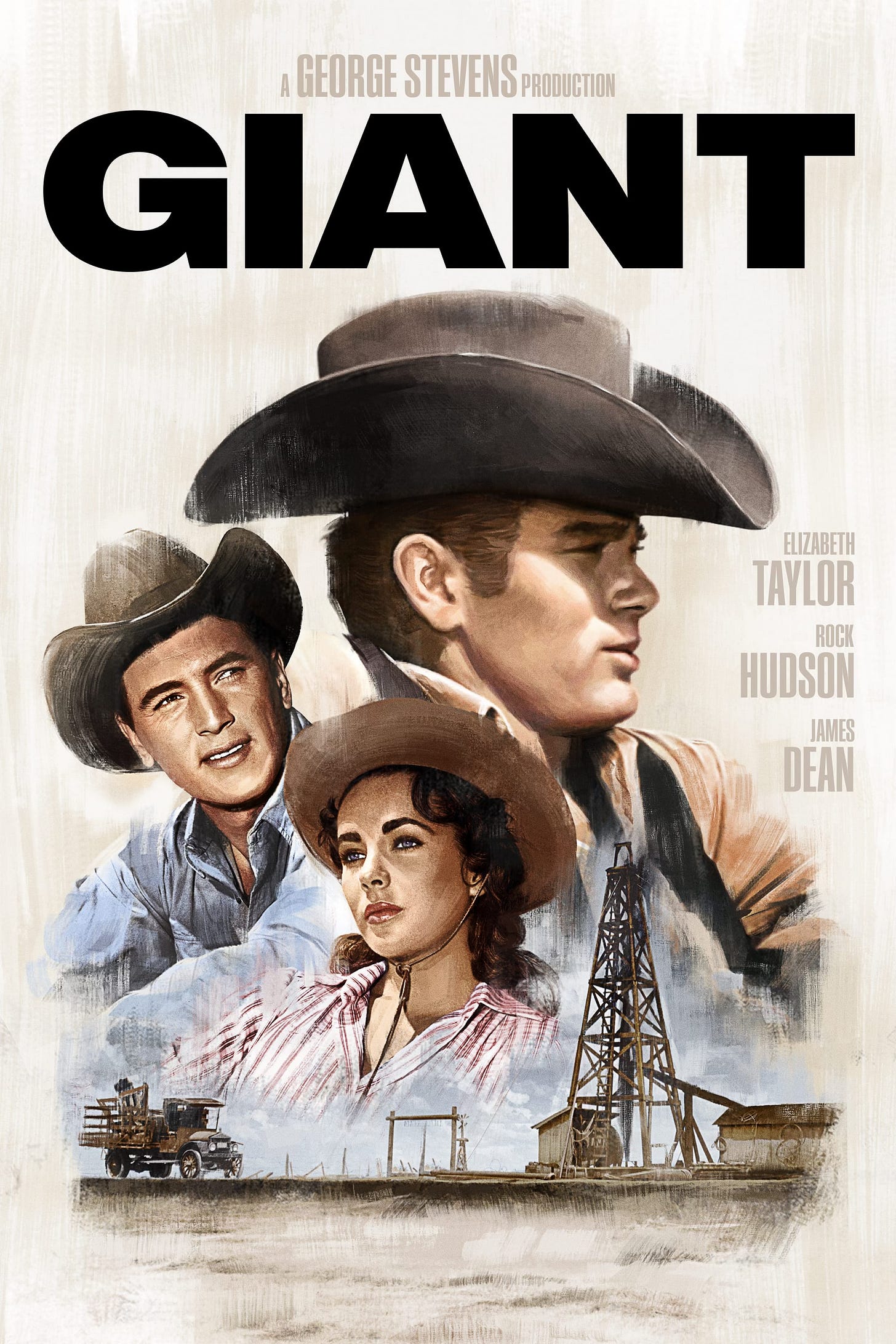

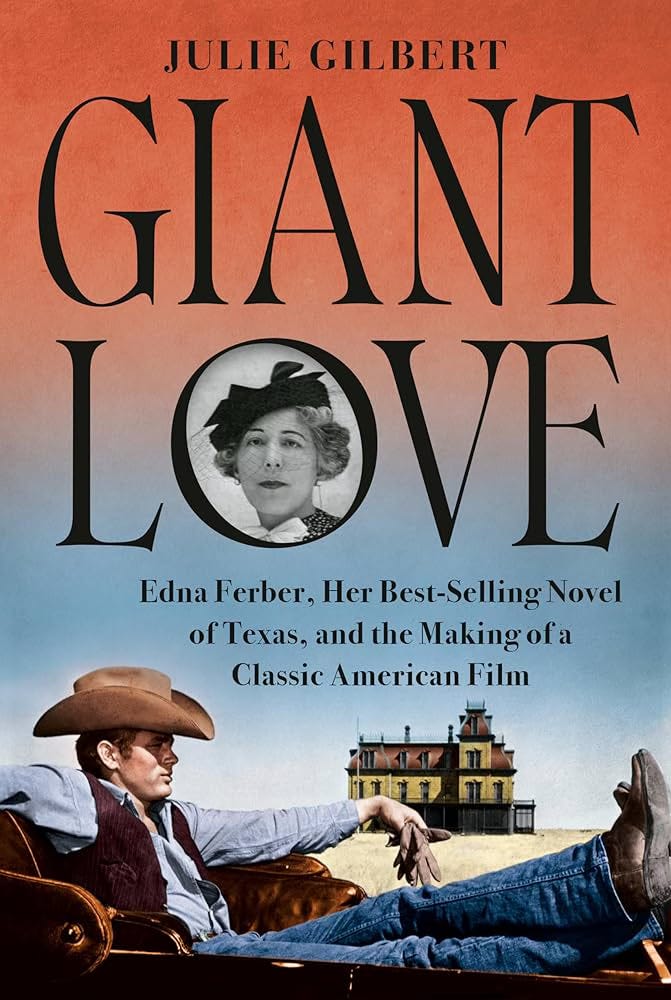

All of this is ably captured in Julie Gilbert’s Giant Love: Edna Ferber, Her Best-Selling Novel of Texas, and the Making of a Classic American Film (2024). Gilbert isn’t the first to write about the making of the 1956 movie of the same title. Don Graham’s Giant: Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, James Dean, Edna Ferber, and the Making of a Legendary American Film came out six year before Gilbert’s book, in 2018. However, what makes Gilbert’s treatise unique is that it possesses something Graham (or others) lack: a personal relationship with Ferber. Gilbert is Ferber’s great-niece. This relationship unlocks aspects into Ferber’s mind and character, especially when it comes to her tenacious and unbending demand that Leslie Benedict (Elizabeth Taylor) be represented just as she’s portrayed in the novel—always ladylike, but with a wicked tongue and uncompromising in improving the plight of the Mexican vaqueros who work for her husband Jordan “Bick” Benedict (Rock Hudson). All of this shows in Gilbert’s work.

Far from being a backstage pass to the making of Giant the film, Gilbert’s book puts us on the train and in the car with Ferber as she travels Texas and talks to folks. Giant Love plops us down at Ferber’s desk and typewriter as she plunked out the characters and plot of her Texas epic, of what, until Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove (1985), became the quintessential Texas novel—at least in the eyes of most Americans, if not in the eyes of most Texans. Whereas McMurtry’s novel was celebrated in Texas, by Texans, Ferber’s novel was, by and large, criticized in Texas, by Texans. Most Texans thought she portrayed them as shitkickers and racists. And those who had achieved wealth, either through wrangling cattle or drilling oil, were painted as wannabe sophisticates. They could wear tuxedos and sip champagne but they’d never get the smell of cow manure off their boots or the stain of oil from under their fingernails.

The novel was so unpopular in Texas George Stevens, the director of the film, halfway joked: “The story’s so hot and Texans object so hotly we’ll have to shoot it with a telephoto lens across the border from Oklahoma.”

All this changed when Stevens bucked-up and decided to shoot exteriors on the Ryan Ranch on the outskirts of the tiny West Texas hamlet of Marfa. He further ingratiated himself to Texans near and far when he opened the set to the citizens of Marfa and hired Robert Hinkle, a Texan, as the dialogue coach to work with the actors, including James Dean, who portrayed Jett Rink. These decisions by Stevens not only proved valuable when the film was shown in Texas, but it cast a new light on Edna Ferber and her novel.

Thanks to Julie Gilbert, all of us can take a fresh look at Giant—including this sticker of a Texan.

✭ ✭ ✭

Julie Gilbert, Giant Love: Edna Ferber, Her Best-Selling Novel of Texas, and the Making of a Classic American Film (New York: Pantheon, 2025), 384 pages, $35.00.

✭ ✭ ✭

Support Y’allogy—

Much obliged, y’all.