Cowboy Character: Toughness

“I was bit worse by bedbugs down in Saltillo.”

Woodrow F. Call

If you look up the word cowboy and your dictionary doesn’t include a photo of Boots O’Neal, you need a new dictionary. The same goes for the word toughness.

Billy Milton “Boots” O’Neal was born in the Panhandle town of Clarendon, Texas in 1932. Except for a brief stint in the U.S. Army in the 1950s, Boots has been cowboying since 1947, when he stomped broncs for the RO Ranch. Since that time, he’s been a top hand at the JA Ranch, the Matador Ranch, the Waggoner Ranch, and the Four Sixes Ranch.

A true cowboy legend and gentleman, Boots is also one of the toughest men you’ll ever meet. He cowboys the old fashion way—on horseback, sleeping in teepees, and eating out of chuckwagons. Just before his ninetieth birthday, he was riding range on the Four Sixes when his mount spooked, went to bucking, and unhorsed him. The fall knocked him out. When he came to, his horse was nowhere in sight and he couldn’t find his phone. Spotting a butte in the distance, Boots decided to walk to it and climb to the top of the bluff. That’s when he discovered his leg was severely broken. Unable to get back to the bunkhouse, he figured the boys would miss him when he didn’t turn up for dinner, or his horse arrived at the barn without him. They’d be out to fetch him directly. The only thing to do was lay there and stay put. He then saw a glint on the ground—the sun reflecting off the glass of his phone. He crawled to it, called the boss, and waited for a truck to pull up.

When I first heard about Boots’s accident on the podcast Cowboy Stories he was recuperating, biting at the bit to get back into the saddle.

Howdy, y’all. Welcome to Y’allogy. Pull up a chair and put your boots up.

Before going on to enjoy a few more minutes of pure Texas goodness, I’d be obliged if you’d consider becoming a subscriber—either paid or free. If you sign up as a free subscriber I’ll send you a baker’s dozen of my favorite Texas quotations. If you sign up as a paid subscriber, or upgrade to paid, I’ll send you the same baker’s dozen of Texas quotations, as well as a chili recipe from the original Chili Queens of San Antonio. Either way, I appreciate your consideration.

Boots is the embodiment of the old-time cowboys, whom Philip Ashton Rollins praised: “The puncher rarely complained. He associated complaint with quitting, and he was no quitter.” Quoting one cowboy by the name of Andy Davis, Rollings passed on this bit of advice for toughening up: “The West demands you smile and swallow your personal troubles like your food. Nobody wants to hear about other men’s half-digested problems any more than he likes to watch a seasick person working.”

It was said of the foreman of the J. H. Ranch on the North Platte—a Mr. Miller—that “He hadn’t any use for a man who wasn’t dead tough under any condition.” Punchers in the old trailing days were a different breed of man than the ones we grow today. The average man today might pay good money for a double latte espresso or a Frappuccino, but the men who worked cattle horseback more than a century ago drank their coffee black. And if that wasn’t strong enough to keep them awake in the saddle, they would, if need be, rub tobacco juice in their eyes. “It was rubbing them with fire,” E. C. “Teddy Blue” Abbott wrote. “I have done that a few times, and I have often sat in my saddle sound asleep for just a few minutes.”

Toughness was (and is) an indispensable characteristic every cowboy possessed—or he didn’t last long as a cowboy. Working with large animals like horses and cattle, cowboys were (and are) guaranteed to get stepped on, bit, kicked, gorged, or thrown at some point. Working outdoors cowboys were (and are) guaranteed to sweat through shirt and chaps in the summer and freeze fingers and feet in the winter. Cowboys suffered through droughts and floods, dust and mud, biting and stinging critters, and the poking, scratching, and tearing of plants and trees. They still do.

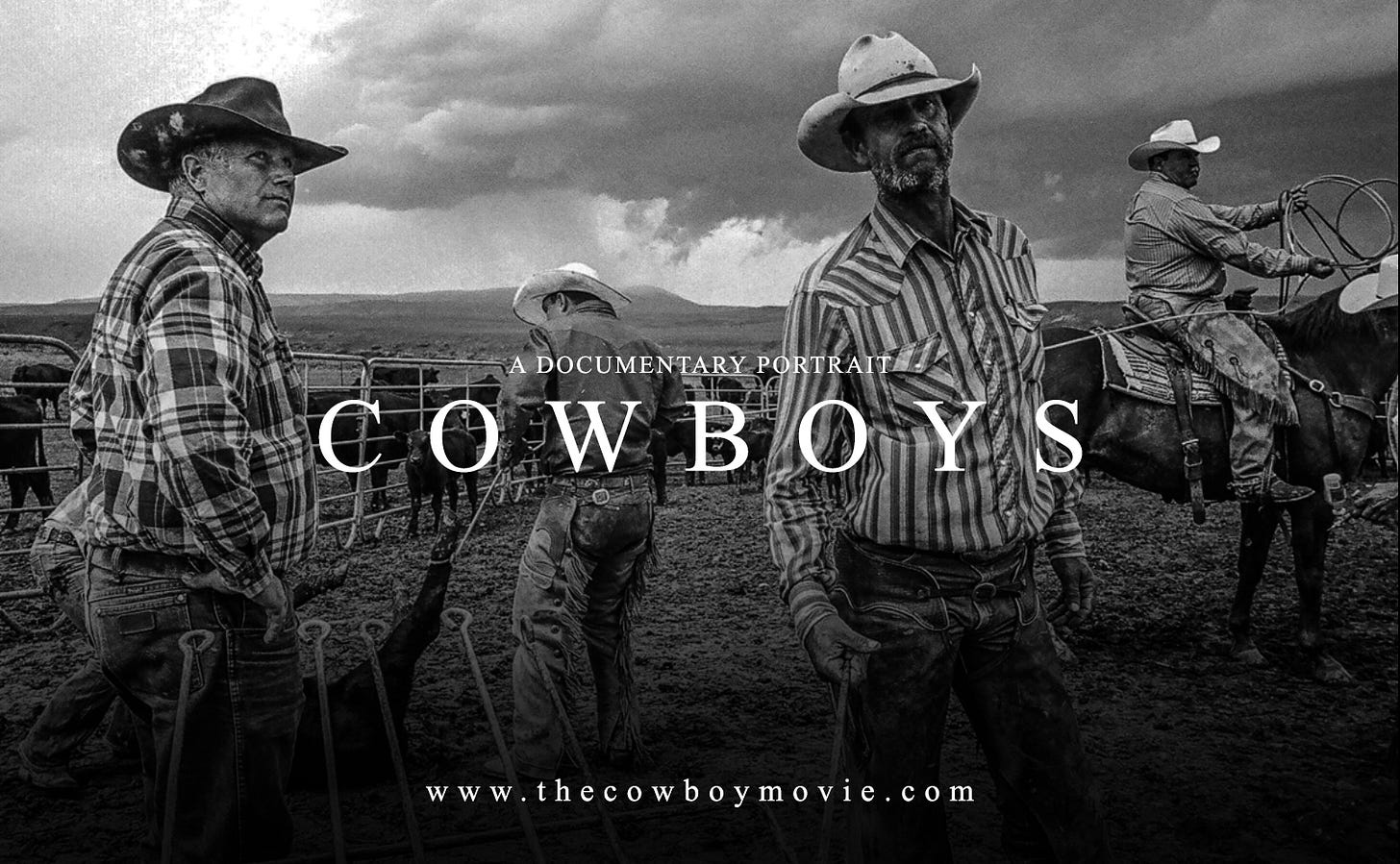

In Bub Force and John Langmore’s film Cowboys: A Documentary Portrait, Ira Wines, the buckaroo boss at the Spanish Ranch in Nevada, tells the story of a trucker from Missouri who didn’t know anything about cowboying, but his lifelong dream was to become one. So, this ol’ boy kept calling Wines asking for a job. Eventually, Wines said okay, if he would learn to shoe a horse, which he did. When the ol’ boy showed up at the ranch he had a brand-new saddle, boots, and hat. The next morning they lit out under the cover of darkness. Wines says that ol’ boy was “chattering like a howler monkey about how he’d found paradise.”

He didn’t chatter long. “We made a pretty big circle and come back up the river,” Wines said. “At two o’clock that afternoon, we’re still trotting and we trotted all day. We got back here to eat lunch, it’s about seven o’clock at night, he walked out of the cookhouse, and I wish I had a video of the way he was walking, ‘cause he didn’t want his pants to touch his legs because I’m pretty sure there was no hide left on them. He said, ‘I don’t know what you guys are made of, but I’m going back to Missouri.’”

Many confuse toughness with strength. They’re not the same. When applied to people (as opposed to objects), strength is the quality or state of being physically powerful. Toughness is the ability to function without flagging under adverse conditions, to withstand rough handling, and to cope with difficulties without complaint. Whereas strength almost always applies to our physical abilities, toughness touches upon the whole person: physically (the ability to endure hardship and injury), mentally (the ability to endure stress and setbacks), and emotionally (the ability to endure heartache and failure).

No one is born tough. But it can be acquired. All it takes is discipline and foregoing small pleasures and comforts. I call it, Eating the Cactus. The idea comes from Texas longhorns—the toughest of the bovine breeds. Next to buffalos, longhorns are perfectly suited to the rough country of South Texas where water is chancy and forge scarce. Longhorns are drought tolerant and, if necessary, can eat poison oak, the bark and leaves of mesquite trees, and prickly pear cactus—needles and all.

I call that tough.

In Larry McMurtry’s Pulitzer-prize winning novel Lonesome Dove, and the television mini-series of the same name, retired Texas Ranger Woodrow F. Call, along with his friend and business partner, former Ranger Augustus “Gus” McCrae, operate the Hat Creek Cattle Company. Early in the novel, Call loses a chunk of flesh from his back when the horse he’s working bites him. Gus thinks Call is crazy, trying to subdue “a Kiowa mare” that the other hands dubbed the “Hell Bitch.” “There’s plenty of gentle horses in this world,” Gus tells his friend. But Call is thickheaded and doesn’t want gentle.

Their old Mexican cook Bolivar, who doubles as the outfit’s doctor, slaps axle grease on the bite with a stick when Call comes in for dinner. The next morning, while watching over his sourdough biscuits baking in a Dutch oven and reading the book of Amos, Gus inspects the bite. “I oughta slop some more axle grease on it. It’s a nasty bite.”

“You tend your biscuits.”

“If you die of gangrene you’ll be sorry you didn’t let me dress that wound.”

“It ain’t a wound, it’s just a bite. I was bit worse by bedbugs down in Saltillo that time.”

That, my friends, is a man who ate the cactus.

Sources:

E. C. “Teddy Blue” Abbott and Helena Huntington Smith, We Pointed Them North (Chicago: R. R. Donnelley and Sons, Co., 1991).

Andy Adams, The Log of a Cowboy: A Narrative of the Old Trail Days (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1903).

J. Frank Dobie, The Longhorns (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990).

Bud Force and John Langmore, directors, Cowboys: A Documentary Portrait (Austin: 1922 Films, 2019), Blu-ray disc.

Larry McMurtry, Lonesome Dove (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1985).

Philip Ashton Rollins, The Cowboy: An Unconventional History of Civilization of the Old-Time Cattle Range (New York: Charles Scriber’s Sons, 1936).