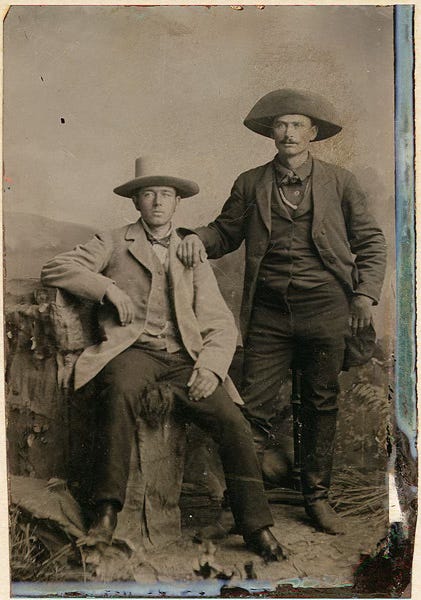

Cowboy Character: Loyalty

Loyalty to friends—that was our religion.

E. C. “Teddy Blue” Abbott

Cowboys are free. It’s one of the reasons why so many folks are attracted, at least viscerally, to the cowboy way of life. Cowboys are free not because they ride horses over open prairies (most of the time the mounts they ride and the grasslands they cross aren’t their own), but because they uphold a character trait that undergirds their freedom.

“Freedom isn’t free,” as the saying goes. Someone has to pay for it. When applied to the military, we say freedom is paid with blood and bone, literally with the bodies of those who fight on our behalf. Only mercenaries put their lives on the front lines for something as sublunary as money. And though soldiers, sailors, and Marines are paid to fight, they’re willing to risk their lives for something more transcendent. We typically call this something more patriotism—love of country. Patriotism, however, is merely a unique synonym for loyalty.

Ask any man who has been shot at and he’ll tell you, in that moment, “the land of the free and the home of the brave” isn’t the reason he fights. In that moment, he’ll tell you the reason he fights is for the man on the right and left of him, because, as Vietnam veteran Karl Marlantes put it, “Warriors deal with eternity.” Loyalty is the reason the soldier, sailor, and Marine enters the fray. Loyalty to their sweat soaked and blood covered buddies.

Cowboys exhibit that same kind of loyalty. With the cowboy in mind, Philip Ashton Rollins wrote that the spirit of the West “nurtured an undying pride in the country of the West, a devoted loyalty to its people as a class, [and] a fierce partisanship in favor of that country and its people.” Teddy Blue Abbott, who pushed cattle up the trail, said it best: “Loyalty to friends—that was our religion.”

Like courage, loyalty shines forth under stress. True loyalty doesn’t shy when faced with disappointment, shirk when faced with difficulty, or slink when faced with danger. Its motto is that of Proverbs 18:24: “There is a friend who sticks closer than a brother.” It stands firm to the end, just as Henry Adams said, “One walks with one’s friends squarely up to the portal of life, and bids goodbye with a smile.”

With his compañeros, a cowboy shared everything but his gal. “He was generous to a fault. Nothing he owned was too good to share with a fellow worker if that puncher needed it,” Ramon Adams wrote. He was loyal to a (near) fault. But there was a limit to his loyalty—he wasn’t slavish about it. His loyalty reined short if enlisted to eschew his ethics or violate the law. This applied to his fellow compadres and the outfit he worked for.

In the popular parlance, cowboys “ride for the brand.” He’s free to draw his wages and come and go, but when he throws his bedroll in an outfit’s wagon and turns out his horse into the outfit’s remuda he pledges his loyalty to that outfit for as long as his bedroll and horse remain in the outfit’s wagon and remuda. Nothing compels him to stay with an outfit other than his own character—his loyalty freely given. He need not be branded with the outfit’s brand to keep him loyal, as took place in the television series Yellowstone. He’s not a member of a gang, nor is he a made man. He need not prove his loyalty. Such notions belie the idea of loyalty freely given, of riding for the brand. They’re perversions of loyalty. Loyalty demanded under threat of damnation is not loyalty, it is slavery.

And the cowboy is nobody’s slave.

So when he says he rides for the brand he means he’s a proud hand for that outfit. His loyalty is given freely and generously accepted. He doesn’t have to be watched or managed. He needs no pocket watch to tell him when to saddle up or when to unsaddle. He’s doesn’t belong to a union nor work by the whistle. The nature of his job requires trust, and he receives it. As one old puncher said of the ranch boss, “Tom Moorhouse either trusts me or doesn’t like me, ’cause he doesn’t tell me me what to do.” In turn, he gives the outfit a day’s work for a day’s wage. He’s tireless in looking after the brand’s interest, and if need be is willing to fight for it, even laying down his life for it, as long as he chooses and rides for that brand.

Cowboy poet laureate Red Steagall captures the spirit of what it means to ride for the brand in these lines:

“Son, a man’s brand

Is his own special mark

That says this is mine, leave it alone.

You hire out to a man,

Ride for his brand

And protect it like it was your own.”

And when a cowboy chooses to strap his bedroll to the back of his saddle, gather up his horse, and ride away, he’s free to find another brand to ride for.

Russell Ronald Reno III, known as R. R. or Rusty, is the farthest thing from a cowboy as you could be. An East Coast intellectual, if he was ever spotted sporting cowboy boots and a hat an authentic puncher would call him a mail-order cowboy, someone advertising a leather shop. And yet, while Reno is no cowboy, he does understand cowboy character, at least the trait of loyalty and it’s link to freedom.

We need loyalty to sustain our liberty. The cowboy isn’t free because he’s free. He’s free because he cherishes his honor above his paycheck, his vocation above society’s fickle acclaim. The red-streaked sunset moves his heart more than calculation of self-interest; a higher loyalty gives him a place to stand. In order to be free we need a higher truth to serve.

I think Reno may have just won his spurs.

Henry Adams, The Education of Henry Adams (New York: The Modern Library, 1996), 503.

Ramon F. Adams, The Cowman & His Code of Ethics (Austin: The Encino Press, 1969), 5, 7.

E. C. “Teddy Blue” Abbott and Helena Huntington Smith, We Pointed Them North: Recollections of a Cowpuncher (New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1939; Chicago: R. R. Donnelley & Sons, 1991), 20, n. 10.

Karl Marlantes, What It Is Like To Go To War (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2011), 44.

R. R. Reno, Resurrecting the Idea of a Christian Society (Washington, D.C.: RegneryFaith, 2016), 36.

Philip Ashton Rollins, The Cowboy: An Unconventional History of Civilization on the Old-Time Cattle Range (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1936).

Red Steagall, “Ride for the Brand,” in Ride for the Brand: The Poetry and Songs of Red Steagall (Fort Worth: Bunkhouse Press, 1993), 13.

Fro Walden, as quoted in Robb Kendrick, Revealing Character: Texas Tintypes (Albany, TX: Bright Sky Press, 2005), 108.

Texan spoken here, y’all.

To support Y’allogy please click the “Like” button, share articles, leave a comment, and pass on a good word to family and friends. The best support, however, is to become a paying subscriber.

Well said. I often hear modern thinkers categorizing "rugged individualism" (who invented that phrase anyway? I'll bet it wasn't a cowboy) as selfishness and being out for one's own interests; but when I read firsthand accounts of Western life and older fiction from writers who knew the time and place, I see its defining characteristic as an independent spirit combined with a strong *voluntary* loyalty to friends and neighbors.

Really enjoyed this! I've been thinking a lot about 'loyalty' recently after discovering that the Greek word for 'faith' as used in the New Testament is 'pistis' which is better translated as 'loyalty'.