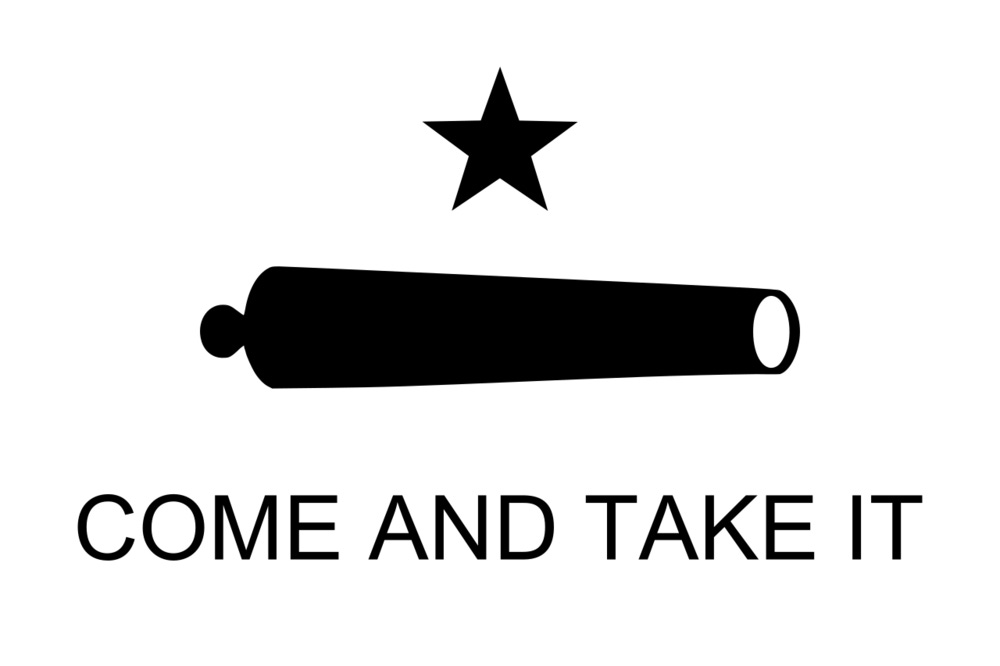

Come and Take It

It was our Lexington. . . . Not a man of us thought of receding from the position in which this bold act had placed us.

Noah Smithwick

Revolutions are often ignited with the tiniest of sparks. The American Revolution began in the spring of 1775 in an unlikely place when someone—soldier or citizen, no one knows for sure—discharged his musket. It was, in the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, “the shot heard ’round the world.” The revolution for Texas independence began in a similar vain, with a skirmish between well-armed soldiers and citizens standing for their rights in an unlikely corner of what would become the Republic of Texas.

Bankrolled by his wife’s sell of her Missouri land, Green DeWitt sought an empresario’s commission from the Mexican government to establish a colony in Texas. Awarded land along the Guadalupe, San Marcos, and Lavaca rivers in April 1825, DeWitt created a settlement for four hundred families just south of Austin’s colony. A veteran of the War of 1812, DeWitt was a shameless promotor of Texas, “as enthusiastic in praise of the country as the most energetic real estate dealer of boom towns” according to one acquaintance. The principle town of DeWitt Colony was Gonzales, named after the Governor of Coahuila. Established on the eastern bank of the Guadalupe, Gonzales boasted blockhouses and a small fort. When these proved ineffective against Indian raids DeWitt petitioned Mexican authorities in 1831 for a canon. The government complied. It sent a small-caliber cannon that fired a six-pound ball to Gonzales.

It wasn’t much of a cannon. According to one report, “it was practically useless, having been spiked and the spike driven out, leaving a touch-hole the size of a man’s thumb. Its principle merit as a weapon of defense, therefore, lay in its presence and the noise it could make, the Indians being very much afraid of cannon.”

With the ratification of the Constitution of 1824, Texians (Anglo Texans) and Tajanos (Mexican Texans) lived virtually unmolested by Mexican authorities. But when Antonio López de Santa Anna declared himself dictator in 1834, repealing the 1824 constitution and disbanding the Mexican government, life in Texas became more difficult. Many Texians and Tajanos rebelled, among them William Barret Travis who forced the surrender of a Mexican commander of the garrison at Anahuac. In September 1835, Santa Anna sent Martin Perfecto de Cos, the commander of Mexico’s Eastern Internal Provinces, to Texas to break up the state government, disarm citizens, and arrest men like Travis—to “let those ungrateful strangers know that the Govno. has sufficient power to repress them.” Cos landed with three hundred soldiers at Capano on the Texas coast and marched to San Antonio de Béxar.

As part of Santa Anna’s disarmament policy Colonel Domingo de Ugartechea, the military commander of Béxar, ordered the Gonzales cannon returned and dispatched a small contingent of the presidial soldiers stationed at the Alamo to retrieve it. Unfortunately for Ugartechea, a Mexican soldier had recently injured a Gonzales townsman in a fight, leaving the citizens sour and uncooperative. The alcalde and other town officials refused Ugartechea’s order. The Colonel then dispatched a hundred dragoons to Gonzales. They reached the Guadalupe on September 29 and found the river swollen by recent rains. Crossings were submerged and ferries and other boats were tied up on Texian side of the river. A shouting match of diplomacy ensued over the torrent. Lieutenant Francisco de Castañeda, commander of the dragoons, said he had a message for the alcalde about the return of the cannon. When he was told the alcalde was away, Castañeda said he’d wait for the mayor’s return. Castañeda had his men pitch camp opposite the town.

While the negotiations between Castañeda and the townsfolk were being shouted across the river, others buried the cannon. A few days later, after word leaked that trouble was brewing in Gonzales, more than a hundred volunteers swarmed in from the surrounding settlements. The cannon was dug up and placed on a wooden carriage. The Texians now outnumbered the Mexican forces. They elected officers, selecting John Moore as colonel.

Though Lieutenant Castañeda was under orders to avoid violence if possible, Colonel Moore decided to force the issue. He and his Texians would cross down river and engage the Mexican dragoons. Before crossing, however, Sarah Seely DeWitt, the widow of Green DeWitt—he having died of cholera, probably, during a trip to Mexico in May 1835—hastily sowed a flag from her daughter’s wedding dress: a large cannon topped with a five pointed start and the defiant challenge COME AND TAKE IT emblazoned underneath. It was in all probably the first Lone Star flag. The men who fought at Gonzales called it the “Old Cannon Flag.”

During the night October 1, 1835, the Texians crossed the Guadalupe, carrying their cannon and war banner. Colonel Moore’s plan was to attack at first light and disperse the Mexicans. A heavy fog from the river shrouded the fields, obscuring their vision, but on the morning of October 2, the Texians approached the Mexican camp and opened fire. At first, Castañeda seemed bewildered. He had not come to start a fight, much less a war, but neither did he want to see his men decimated. Outnumbered, Castañeda withdrew to a more defensible position and offered to parlay. One Texian left an account of the negotiation:

The Mexican commander, Castañeda, demanded of Colonel Moore the cause of our troops attacking him, to which Colonel Moore replied that he had made a demand of our cannon, and threatened, in case of refusal to give it up, that he would take it by force; that this cannon had been presented to the citizens of Gonzales for the defense of themselves and of the Constitution and laws of the country; that he, Castañeda, was acting under the orders of the tyrant Santa Anna, who had broken down and trampled underfoot all the state and federal constitutions in Mexico, excepting that of Texas, and that we were determined to fight for our rights under the Constitution of 1824 until the last gasp.

Castañeda replied that he himself was a republican . . . that he did not wish to fight the Anglo-Americans of Texas; that his orders from his commander were simply to demand the cannon, and if refused, to take up a position near Gonzales until further orders.

Colonel Moore then demanded him to surrender with the troops under his command, or join our side, stating to him that he would be received with open arms, and that he might retain his rank, pay, and emoluments; or that he must fight instantly.

Castañeda answered that he would obey orders.

When Colonel Moore returned to the Texian lines, he fired the cannon, charged with metal scraps. Other Texian began firing Kentucky long rifles, shotguns, and fowling pieces as they advanced on the dragoons. Castañeda abandoned the field, suffering perhaps two men, and retreated back to San Antonio. He explained his withdrawal to Colonel Ugartechea: “Your Lordship’s orders were for me to retire without compromising the honor of Mexican arms.”

Though the battle of Gonzales was hardly a strategic victory, it was a tactical victory, and a fateful step in the revolution for independence, as Noah Smithwick explained in his often times too-colorful memoir:

It was our Lexington, though a bloodless one, save that a member of the “awkward squad” took a header from his horse, thereby bringing his nasal appendage into such intimate association with Mother Earth as to draw forth a copious stream of the sanguinary fluid. But the fight was on. Not a man of us thought of receding from the position in which this bold act had placed us.

And then, like John Adams who wrote after Lexington that the American colonists “We were about one third Tories, and [one] third timid, and one third true blue,” Smithwick wrote:

I can not remember there was any distinct understanding as to the position we were to assume toward Mexico. Some were for independence; some for the constitution of 1824; and some for anything, just so it was a row. But we were ready to fight.

And fight they did.

Texan spoken here, y’all.

To support Y’allogy please click the “Like” button, share articles, leave a comment, and pass on a good word to family and friends. The best support, however, is to become a paying subscriber.