Christmas 1887 in Palo Duro Canyon

There wasn’t a hill between us and the North Pole.

J.C. Tolman

In the winter of 1887, J.C. Tolman worked as a cowhand on the XIT Ranch in the Texas Panhandle. His father, Thomas, had been a Lieutenant in the Sixth Cavalry under the command of Major George Armstrong Custer. As J.C. told it, his father became gravely ill while the Sixth was stationed at Camp Sanders in Austin. A local woman, Jinnie Barret, asked Custer to allow Thomas to convalesce in her home. Fearing Thomas would die, Custer granted her request. But Thomas didn’t die. He was nursed back to health by Mrs. Barret and her daughter Corinne. When Thomas gained enough strength, he and Corinne would ride to Mount Bonnell, a 775 foot mound of rock overlooking Austin. Legend had it that a couple would fall in love on their first visit to the summit, become engaged on their second climb, and marry on their third. On Christmas Eve 1866, Thomas and Corinne were engaged—their second visit to Mount Bonnell. The couple soon married—presumable after their third visit to Mount Bonnell—and had J.C.

Prairie fires were common on the grasslands of the Panhandle in the 1880s—still are. While wildfires replenish nutrients for new growth, they are devastating to ranching operations, consuming fences, corrals, barns, homesteads, and cattle. To help control fires, a crew from the XIT’s Escarbada Division spent two years cutting firebreaks and surveying sections of the Panhandle. In December 1887, while surveying near Palo Duro Canyon an unexpected norther blew down the plains catching Tolman and the surveying crew in the open. “There’s nothing between Amarillo and the North Pole but a barbed-wire fence,” as the saying goes. If you’ve ever been in that part of the country when a norther blows though you know how quickly you can freeze. The only means of survival for the surveying crew was to make for the canyon.

What follows is a portion of the tale of that fridge flight to the Palo Duro on Christmas Eve and the night spent in the canyon.

. . . We . . . stopped on the brink of the Palo Duro Canyon.

To see the sight in front of us was enough to make the heart miss a beat. It could not be looked upon without causing the beholder to thrill with appreciation of the wonderful works of the Great Architect of the universe.

Here, the result of the slow erosive action of waters through hundreds of thousands—perhaps millions—of years, was a gash cut through the plains for fifty miles. In places over a thousand feet deep and five miles in width, it is one of the wonder spots of America. Along the rim we saw a band of yellow, where the plains grass dipped to the rim-rock. This rim-rock, a heavy band of gray, capped the canyon as far as the eye could reach. Below it the exposed strata showed as through some giant hand had drawn brushes, dipped in many colors, along the miles of the canyon walls. Pink, blue, red, gray, green yellow, purple, brown, blending in the distance into a lovely purple shade. At intervals were ledges clothed with the deep green of tall cedars. Diamond-like points of light were reflected from springs gushing out of the rocks to fall in terraced cascades and to be lost in the sand and gravel at the bottom of the gorge.

We gazed in silence for a long, long time. The air was like crystal in the canyon that crisp winter day. . . .

There had been no very severe weather. Rather warm days and cool delightful nights. The air was like fine wine. Work was a vast delight. Sleep under the stars was a dip into the fountains of perpetual youth.

One of the wagons had gone to town for supplies and returned two days before Christmas. On the morning of the twenty-fourth we broke camp and the heavy wagons started for a new camp site several miles to the east of where our first line had crossed the canyon. The line crew went several mile to the north and started to run a line south toward the new camp. All went well until about the middle of the afternoon.

Dave had just taken a front-sight and given the “O.K.” signal to come ahead, when we saw him wave his arms in a signal which meant “Look.” He seemed to point to the north. We looked, but could see nothing unusual. When we reached Dave and asked what was the matter, he answered, “Norther coming,” and loped off for another sight. There did seem to be a slight haze in the north—low down on the surface of the plains.

When we reached the next hub and looked back, there was a dun-colored arch distinct above the plain, far to the north. At the next stop we established a corner and dug four pits and built an earth mound. I remember we were quite warm from the work. By the time we were through this—hardly three-quarters of an hour from the time Dave’s sharp eye had seen the approaching norther—the dun-colored arch extended to the horizon from east to west and was almost upon us from the north. It did not extend very far above the plains. P.G. gave the order to quit work and make for the camp.

The outfit moved with celerity. The Major and [his mount] Old Sideways had gone south some time before. Dave and Martin let their ponies lope. Sebe shook the rains at his longlegs light-wagon team and they galloped madly away from the storm. But it caught us in a few minutes. With a rush of ice cold wind, a snarl like an angry beast, an awful roar, changing into a long drawn out wail which continued to rise and fall—the yellow norther of the plains struck and enveloped us.

The air was full of ice-needles that drove into the exposed flesh and stuck, but did not seem to melt. The snow seemed to parallel the ground in its flight; yet the plains grass was covered by it in a few minutes and it rolled along the ground with the wind. That wind didn’t turn aside. When it hit you it just kept right on through your body, as though your flesh offered no obstruction to it. There wasn’t a hill between us and the North Pole and that wind must have come all the way—and gathering power at every jump.

We had been sweating ten minutes before. Now we pulled the wagon sheet over us huddling under it. But the wind and cold were pitiless and cut and stung despite the cover.

Sebe let his mules run for several miles. They ran straight south and made no effort to turn. The norther attend to that.

We couldn’t see ten feet ahead of the team, but we knew that somewhere ahead of us was a thousand foot canyon with sides nearly straight down for several hundred feet. We knew we had gone a long way and we thought we were within a mile of the cap-rock, when those two Missouri mules suddenly stopped. Fortunately nothing broke, and we managed to stay in the wagon.

Sebe pulled to the left and urged the team. They didn’t want to turn sideways to the wind and sleet, but Sebe managed to make them move. Almost immediately we started down the grade and in less than half a minute were below the plains level.

Sebe turned the team to the right, and we scrambled down on to a bench, high above the bottom of the canyon, but two hundred feet below the top of a precipice of solid rock.

The wind roared far above us, but there was no gust that reached to our level. The snow fell in sheets about us, but dropped calmly straight down. And there, by our good luck, was the camp. The teamsters had pitched the tents—a courtesy extended only in times of stress—and Old Bill had a fire going and supper well on the way.

After we had thawed out and moved around a bit, one of the boys noticed a cleft in the face of the precipice about thirty feet above its base and in the cleft were three or four dead cedars. He threw a blazing pice of wood up into the dry limbs and it hung there and set fire to one of the trees. In a short time we had a roaring torch fifty or sixty feet tall. We ate supper by its light and shortly thereafter the trees burnt off from the stumps and a wonderful avalanche of flaming wood and coals piled itself at the base of the rock. It burnt for hours and warmed quite a large space around camp.

When we had finished “first smoke,” P.G. announced that he had a new novel by “The Duchess” and would read some to us. We helped Old Bill wash the dishes so that he could hear the story, he being naturally romantic and a great admirer of The Duchess.

The light from the great fire was sufficient and we gathered around P.G. and listened as he read of real high-toned society folk—even an occasional nobleman and titled lady—who entered the scenes with perfect grace and beauty and who made love in a most delicate and refined way. It was all so different from what we knew!

Late at night, while P.G. was reading a very tender passage, he was interrupted by a maniacal chorus of shrieks and howls—deep-throated, menacing, and terrifying. The reading ceased until the pack had yelled their way a long distance from our sheltering bank over the snow-covered plain. The lobo wolves were hungry and were hunting.

Again P.G.’s voice took us back to the tenderness and beauty of the Irish land and we thrilled with the hero and laughed with “Dickey Browne.”

The light from the fire died down; but the glowing coals still melted the snow around us. Old Bill lit a lantern and placed it on a tomato box by P.G’s shoulder.

The Duchess was no mean writer, and her descriptions of garden fetes, picnics, balls, and love-making gripped and held us. We were all young, in years at least, and each one saw himself the hero of the tale, and each made the delicate remarks at the proper time, and, at the end, each of us thrilled to the kiss of promise of the lovely heroine.

P.G. finished the tale and we sat awhile in blissful silence. Then Dave murmured: “That’s a hum-dinger of a love story!”

“Let’s go to Ireland on a cattle-boat,” suggested Martin.

“Sure! Let’s!”

P.G. looked at his watch. “Good gracious! It’s past one o’clock! Merry Christmas!”

We all shook hands all around. Old Bill sighed very deeply: “It sure started fine, Chief. I looked at my watch just at twelve, an’ that cuss was puttin’ his arm around that lady for the first time; and it was a Christmas Eve and she wished him, ‘Merry Christmas.’ Dogon the luck! G’night.”

Source & Notes:

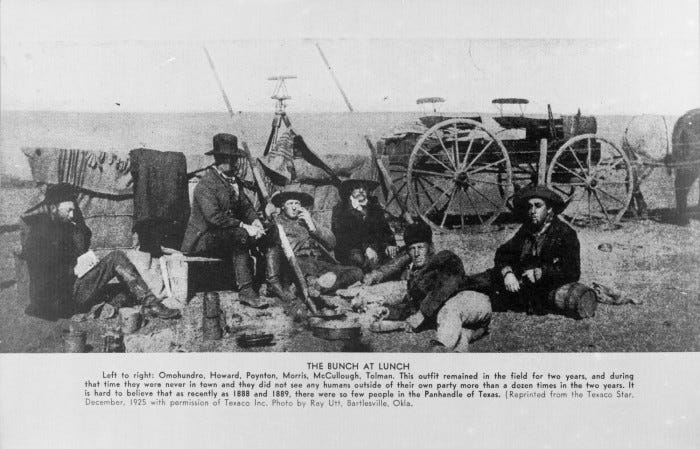

J.C. Tolman, “Christmas 1887 in Palo Duro Canyon,” in The Texaco Star, vol. 22, no. 12 (December 1925), 19–22.

P.G. is Philip Grymes Omohundro. Born in Charlottesville, Virginia, he moved to Texas in 1884. Whether he worked as a cowboy on the XIT in 1887 is unknown, but he was the surveying chief for the work crew in this story. Later in life, he worked as a surveyor for the Sun Oil Company.

The Duchess was the pen name of Margaret Wolfe Hungerford, Irish author of popular romantic fiction. The novel P.G. read to the crew was most likely Portia; or “The Passions Rocked,” published in 1883. (The character “Dickey Browne” is spelled Dicky in the novel.)

The article you just read was 1836% pure Texas. I hope you enjoyed it. If you did, show it by clicking the heart (♥︎) button, leaving a comment, creating a discussion thread on Chat, or posting this article to Notes and other social media platforms to let your Texas-loving friends know about Y’allogy.

As a one-horse operation, I depend on faithful and generous readers like you to support my endeavor to keep the people, places, and past of Texas alive. If you share those same passions, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. As a thank you, I’ll send you a free gift.

Find more Texas related topics on my Twitter page and a bit more about me on my website.

Dios y Tejas.