Beautiful Violence

“[War] endures because young men love it and old men love it in them.”

The Judge, Blood Meridian, Cormac McCarthy

Artistic ugliness. Beautiful violence.

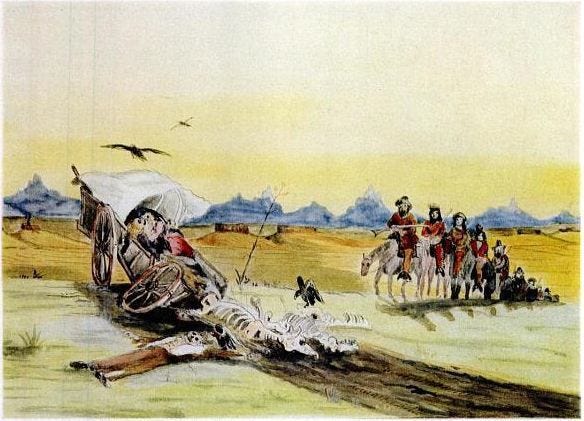

This is what I thought as I read Cormic McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. His brilliance as a stylist is unsurpassed as a modern American novelist. The rich beauty of his language in depicting ugly characters who lived during ugly times, engaging in ugly exploits is both engrossing and gross. His descriptions of violence and death are disturbing, but painted with such vibrant colors and intricate detail you are drawn to his narrative like a coyote to a dead body.

Blood Meridian is a simple story, staring a cast of complex characters. On the surface, the story is about a gang of cutthroats hired by the Mexican governor of the state of Chihuahua to track down and gather Apache scalps. Loosely based on real events recorded in Samuel Chamberlain’s My Confess: Recollections of a Rogue, McCarthy turns the bloody business of scalp hunting into a bloodlust. Violence begets violence until not even those in the gang are safe from passing under the guns and knives of their compadres. The worst of the worst of this sordid lot is the Judge.

As one of the most interesting and enigmatic characters ever to cross my path, the villainy of the Judge ranks with Herman Melville’s Ahab in Moby Dick, Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz in Heart of Darkness, and Colonel Kurtz in Frances Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (based on Conrad’s novella). The Judge is a fat, albino-like, hairless man who embodies evil. Intelligent, cool, and calculating, the Judge takes on a Satanic demeanor in his opposition to Christianity. Slandering Reverend Green as a child molester and pervert during a worship service in Nacogdoches, Texas leads to mod violence and a posse to track down Green to hang him. The Judge later admits that he had never seen or heard of Reverend Green before arriving in Nacogdoches.

But more than opposition to Christianity is at play in the Judge’s demonic character. He also presumes to rule the world order and is often depicted in pagan rituals, most vividly in his wild incantation to create gunpowder out of bat guano, charcoal, and human urine. Completely careless about decorum or morality, the Judge is often seen naked and McCarthy hints at homosexual activities with younger men and boys.

In one of the Judge’s speeches he discusses the human love of war. Summing up that violence will never abate because “young men love it and old men love it in them.” In the concluding paragraph McCarthy depicts this love of violence with almost ritual-like rhythm.

And they are dancing, the board floor slamming under the jackboots and the fiddlers grinning hideously over their canted pieces. Tower over them all is the judge and he is naked dancing, his small feet lively and quick and now in double time and bowing to the ladies, huge and pale and hairless, like an enormous infant. He never sleeps, he says. He says he’ll never die. He bows to the fiddlers and sashays backwards and throws back his head and laughs deep in his throat and he is a great favorite, the judge. He wafts his hat and the lunar dome of his skull passes palely under the lamps and he swings about and takes possession of one of the fiddles and he pirouettes and makes a pass, two passes, dancing and fiddling at once. His feet are light and nimble. He never sleeps. He says that he will never die. He dances in light and in shadow and he is a great favorite. He never sleeps, the judge. He is dancing, dancing. He says that he will never die.

Concluding as he does, McCarthy transforms the Judge from a mere human to a demon of violence to the embodiment of warfare itself. It is violence that dances through the ages, that never sleeps, that never dies.

McCarthy ends with an intriguing epilogue. A man makes holes in the ground. He is followed by other men who move in rhythm with him. Many theories have been offered as to the meaning of the epilogue. Here’s mine. The man digging holes is digging holes for fenceposts. The men following plant the posts and string barbed wire. McCarthy’s books is the story of the old, Old West—of a west of freedom, wide open spaces, and untamed violence. McCarthy’s epilogue is the story of the new, Old West—of a west of quarter section pastures, civilization, and tamed violence. What was will never be again, not in the age of barbed wire and civilization ... though violence and war never sleep and never die.