A Texan in the Court of St. James

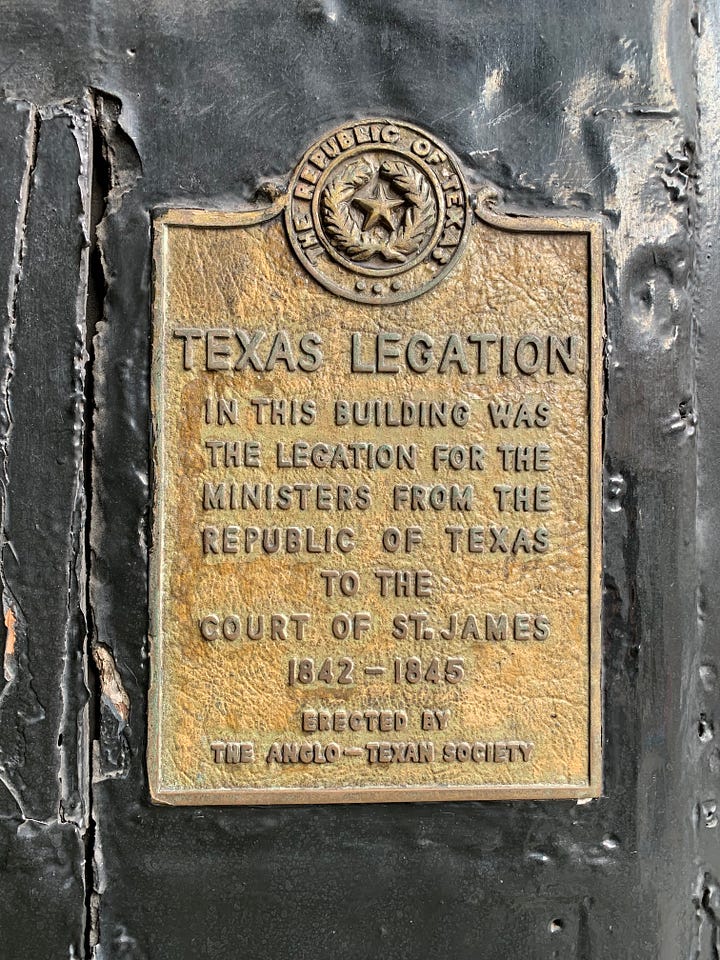

In this building was the legation for the ministers from the Republic of Texas to the Court of St James, 1842–1845.

Plaque at No. 3 St. James’s, London

When King William III made St. James’s Palace the primary residency for the English monarchy, after a fire destroyed Whitehall Palace, the Court of St. James became the center of the universe, not only for foreign dignitaries, but also for London’s foppish gentlemen who gathered to drink spirits, conduct business, and discuss politics at one of the gentlemen’s clubs located on St. James’s and Pell Mell—the streets intersecting the palace.

In the same year William III moved into St. James’s Palace, 1698, a Mrs. Bourne, opened a grocery story at No. 3 St. James’s, just a few doors from the palace’s front gate. From here, Widow Bourne and her two daughters operated a thriving business, catering to upper crush clientele with fresh produce, meats and fishes, and wine. Hidden away in the back, hemmed in on three sides by the store and residences, was a small courtyard—Stroud Court.

In time, Widow Bourne’s daughter Elizabeth married William Pickering, who assumed operation of the grocery store, to which he added a coffee mill, suppling St. James’s fashionable coffee houses with the latest blends. The mill soon became a cash boon. The store became so identified with the coffee mill, Pickering had a sign painted to represent their principle commodity. Today, if you visit No. 3 St. James’s you’ll see the “Sign of the Coffee Mill” hanging from the façade.

With coffee profits percolating, Pickering rebuilt Stroud Court (now Pickering Place) and No. 3 St. James’s into the Georgian-style building seen today. At his death, in 1734, Elizabeth ran the business alone, until their two sons, William Jr. and John, were old enough to undertake responsibility of the shop. They diversified the business to include the painting of heraldic coats-of-arms for the gentry who occupied the Court of St. James.

When John died in 1754, William Jr. formed a partnership with John Clarke, a relative. It was during their tenure, in 1760 that the shop supplied food stuffs to the Court of George III (the king who lost the American colonies). In 1765, the grocer’s weighing scale became a popular attraction. The shop’s well-heeled clientele, including royal princes, Lord Byron, Beau Brummel, and William Pitt the Younger, turned weighing themselves into a favorite pastime. Today, you can ask to be weighed on the same scale.

Within forty-five years, John Clarke’s grandson George Berry had taken over control, painting his name across No. 3. St. James’s. George wasn’t interested in groceries or coffee, but in wines and spirits. Under his influence, and that of his sons George Jr. and Henry, the business divested itself of groceries and coffee, and sold wine and spirits exclusively. From that time to the present-day, Berry Bros. & Rudd (a family which joined the business in the early twentieth century) has become merchants of fine wines and ardent spirits to the haut monde of London.

You might be thinking, This is interesting English history, Derrick, but isn’t Y’allogy a newsletter about the people, places, and past of Texas? Where does Texas fit into this story about No. 3 St. James’s and Berry Bros. & Rudd?

Well, I’m gonna tell y’all.

An arched and dark passageway at No. 3 St. James’s is the entrance to Pickering Place, the small courtyard formerly known as Stroud Court. Its own history is fascinating. Not only is it the smallest of London’s public squares, it was the location where gentleman once amused themselves with dice and card and bloodsports, betting on bear-baiting and cock-fighting. It was also the place where blood disputes were settled with swords. According to legend, Beau Brummel, a close friend of King George IV and inventor of the cravat, killed a man in a duel there. According to history, in 1812, it was the location of the last deadly duel in London. The names of the participants and the outcome, unfortunately, have been lost to time. Pickering Place was also the one time home of exiled Napoleon III (1838–1848), who used the cellars of Berry Brothers to hold secret meetings, as well as British novelist Graham Greene.

Down the dark corridor leading to Pickering Place is a lone door with a single sconce to illumine it—No. 4 St. James’s. It was behind this door and up the stairs, at least for a short time, from 1842–1845, that the adolescent Republic of Texas founded its legation (a diplomatic outpost ranking lower than an embassy), headed by a chargé d’affaires (a diplomat ranking lower than a full-fledged ambassador). While the United States recognized Texas’s independence in 1837, there was great reluctance to annex the fledgling republic. With invasion from Mexico an imminent and existential threat, Texas sought to mitigate that possibility, as well as bolster its depressed economy, by establishing legations in the capital cities of international powers: the United States, France, and England.

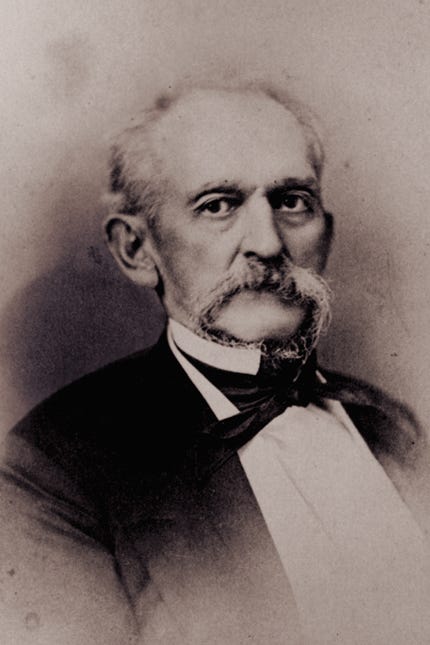

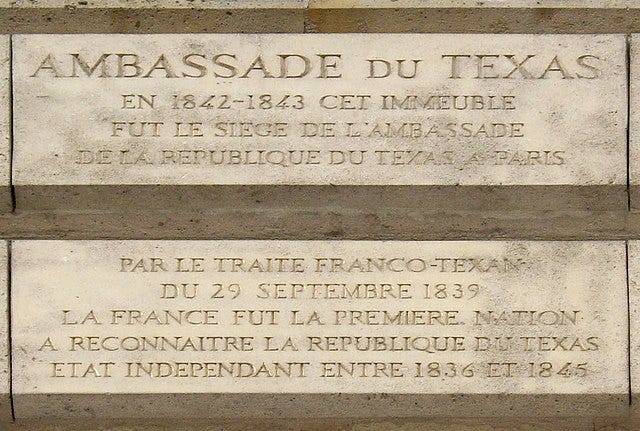

The Republic of Texas had two chargé d’affaires in London and Paris. President Sam Houston appointed George S. McIntosh secretary of the Texas Legation in England and France on June 20, 1837, though there was no official location for either legation at the time, nor at the time an official chargé d’affaires. In 1839, McIntosh was promoted to chargé d’affaires. He was replaced by Dr. Ashbel Smith in 1842, who established official locations for the Texas Legation in Paris (1 Place Vendôme, now the Hôtel Bataille de Francès where a commemorative plaque is carved into the façade of the building) and London (No. 4 St. James’s). Berry Brothers were no doubt happy to have the Texas Legation as a neighbor and tenant since their previous tenant had operated a notorious gambling den and whorehouse—one of the many “Hells,” as they were popularly known, within the city of London.

More important than finding a location to house the legation, Smith secured ratification of a treaty of amity and commerce with England and smoothed over relations with France after the Pig War incident, in which France’s chargé d’affaires to Texas, Alphonse Dubois de Saligny, accused his Austin landlord, Richard Bullock, of failing to control his pigs. According to Dubois de Saligny, Bullock’s pigs ate the corn the Frenchman fed to his horse and broke into his room, destroying state papers and linen. Bullock accused Dubois de Saligny of ordering his servants to kill several of Bullock’s pigs, resulting in a beating of Dubois de Saligny’s servants by Bullock, and a threat of physical violence on the Frenchman himself. Dubois de Saligny invoked the “Laws of Nations,” claiming diplomatic immunity, and demanded Bullock be punished by the Texas government. They refused. In protest, Dubois de Saligny, acting on his own according and without instructions from Paris, broke diplomatic relations with Texas. In May 1841, he left the country and retired to Louisiana, where he issued dire warnings to the Republic’s government that France would exact terrible retribution for the way he had been treated.

While the official French position supported its chargé d’affaires, the government privately resented Dubois de Saligny’s highhandedness and bold departure without consultation or permission. As such, they had no intention of squeezing the Republic of Texas. Instead, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, François Guizot, negotiated with Ashbel Smith to settle the matter.

More significant than resolving the so-called Pig War, however, Smith encouraged European immigration to Texas, thus enlisting friendly European powers to mediate with Mexico in order to temper their treats of a Texas invasion.

Smith’s tenure as chargé d’affaires in both London and Paris was short-lived. In 1844, talk of annexation found new footing in the John Tyler administration. After intense negotiations, and Mexico’s continued refusal to recognize the Lone Star Republic or quiet its sword, Texas chargé d’affaires in Washington, Isaac Van Zandt, and U.S. secretary of state, John C. Calhoun, signed a treaty of annexation on April 12, 1844. Ten days later, Tyler sent the treaty to the U.S. Senate for ratification. On June 8, they rejected the treaty by a vote of 35–16. By October, the British government washed its hands of trying to broker a deal between Mexico and Texas.

The presidential election of 1844 changed everything. James K. Polk resurrected the hopes of Texas annexation, but this time it would move forward as a joint resolution, requiring only a simply majority. Most agreed, even those opposed to annexation, that it was more a question of how and when rather than if Texas was admitted into the Union.

U.S. House representative Milton Brown of Tennessee figured out the how. He wrote the bill paving the way for Texas annexation. It passed the House on January 24, 1845. The Senate debated the bill throughout February, eventually voting on the twenty-seventh. The vote was a tie: 26-26, rendering the bill dead. But at the last minute Henry Johnson of Louisiana changed his vote and the measure was adopted 27–25.

There were formalities to be worked out in Texas—a vote by the Texas Congress to accept the U.S. offer, a public vote by the people, and the writing of a state constitution. When that was accomplished, the U.S. Congress formally voted to admit Texas into the Union and President Polk, on December 29, 1845, signed Texas annexation into law, making Texas the twenty-eighth state.

Once Texas joined the Union of States, it no longer needed its legations in London and Paris. Ashbel Smith locked the doors behind him for the last time and sailed home. When he left London, however, he forgot to pay the rent, stiffing Berry Brothers £160.

One hundred and eight years later, in 1953, Graham Greene—the same British novelist who lived at Pickering Place—along with British film producer John Sutro formed the Anglo-Texan Society in London. Green served as its first president. The idea of the Society was to develop friendly relations between Britons and Texans by sponsoring cultural exchanges, and for Britons to look after Texans traveling to jolly ole England. Membership was open “to persons of either sex who have some definite connections with both Texas and Great Britain.”

The Society’s first function was a barbecue, held in London on March 6, 1954—Alamo Day—to commemorate Texas independence (March 2). It was attended by 1,500 guests. On the menu was 2,800 pounds of beef, donated by the Houston Fat Stock Show.

In 1963, under the leadership of Sir Alfred Bossom, a former member of Parliament, who had extensive connections in Texas, the Anglo-Texan Society erected a brass plaque at No. 3 St. James’s, on the corridor leading to Pickering Place, to mark the location (at No. 4 St. James’s) of the Texas Legation to the Court of St. James. Governor Price Daniels Sr. was the guest of honor and unveiled the plaque. It reads:

TEXAS LEGATION

In this building was the legation for the ministers from the

Republic of Texas to the Court of St James

1842-1845

Erected by

The Anglo-Texan Society

The Anglo-Texas Society disbanded in May 1979.

Post Script: On the sesquicentennial of Texas independence, March 2, 1986, twenty-six Texans dressed in buckskin regalia showed up at the door of No. 3 St. James’s. They had come to pay the debt the Republic of Texas owned Berry Brothers. They paid the legation’s former landlords in Republic of Texas banknotes.

I was referring to the line in the 2023 piece:

"...and discuss politics at one of the gentlemen’s clubs located on St. James’s and Pell Mell—the streets intersecting the palace."

I thought perhaps clippy was still waging his spell check revenge.

I think that it is Pall Mall street. Pell-mell means something else

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pall_Mall,_London