A Damned Amusing Sign

“That’s a damned amusing sign. . . . I never expected to meet Latin in this part of Texas.”

Wilbarger, Lonesome Dove

Larry McMurtry’s best known and most beloved novel Lonesome Dove is a story of friendship, love found and love lost, and adventure. It’s also about change—old ways giving way to new ways and the transformation of a timid boy into a confident man. I don’t know if McMurtry was familiar with the old cowboy proverb, but he certainly would approve of it: “A change of pasture sometimes makes the calf fatter.” Sometimes—that’s the key. Sometimes the calf refuses to fatten, and Lonesome Dove is about that too.

The theme of change, and the refusal to accept change, is summarized in the enigmatic sign Augustus McCrae paints for the Hat Creek Cattle Company. To the irritation of his partner, Woodrow F. Call, Gus ends his sign with “We Don’t Rent Pigs.” Satisfied with his handiwork, Gus grows dissatisfied a few years later and decides “it would add dignity to it all if the sign ended with a Latin motto.” Gus doesn’t know Latin but he carries in his saddlebag an old textbook that had belonged to his father. In the back was a collection of Latin phrases. That they aren’t translated doesn’t bother Gus none. “It was his view that Latin was mostly for looks.” Finding an attractive one, he paints it at the bottom of the sign: Uva uvam vivendo varia fit.

When Call notices he asks Gus, “Wasn’t the part about the pigs bad enough for you? What’s the last part say?” Unperturbed, Gus responds, “It says a little Latin.” “So what’s it say, that Latin?” Call wants to know. “It’s a motto. It just says itself.” Call scoffs, “You don’t know yourself. It could say anything. For all you know it invites people to rob us.” Gus laughs. “The first bandit that comes along who can read Latin is welcome to rob us, as far as I’m concerned. I’d risk a few nags for the opportunity of shooting at an educated man for a change.”

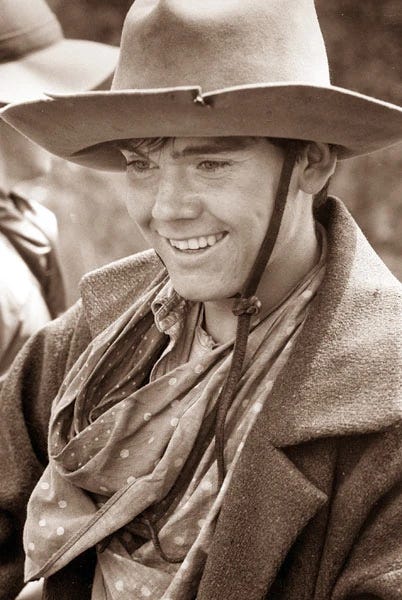

Such a man came by, not rob the Hat Creek outfit but to buy horses—as the sign said. He was the only one who appreciated Gus’s placard. “That’s a damned amusing sign,” he said. “I never expected to meet Latin in this part of Texas but I guess education has spread.” His name was Wilbarger.

After it’s publication, and despite the Pulitzer Prize, McMurtry was dismissive of Lonesome Dove. “It’s just a book,” he said in an interview. “The fact that people connect with it and make a fetish out of it is something I prefer to ignore. . . . I don’t think much about my books.” Be that as it may, he thought enough of his books, including Lonesome Dove, to speak and write about the background of the story, how he came upon the name for the novel, and how he developed the characters of Gus and Call in particular. And in a letter to Ernestine P. Sewell, an English professor at East Texas State University (now Texas A&M University-Commerce), McMurtry revealed that he found the Latin phrase in William Gurney Benham’s Putnam’s Complete Book of Quotations.

Benham doesn’t attribute the Latin phrase to the second-century Roman poet Juvenal, but his entry is exactly what Juvenal wrote in his critique of the moral decay in Rome: Uva uvam videndo varia fit—The grape changes its color (ripens) by looking at (touching) another grape (Satires, 2.81). McMurtry either incorrectly copied the word videndo or purposely misspelled it as a subtle wink to Gus’s ignorance of Latin since the Hat Creek sign reads vivendo. That’s just one mystery. The other mystery is whether McMurtry intended Gus’s motto to be merely a clever addition in keeping with Gus’s character (which it is), in that he found a phrase that looked good but doesn’t know what it means, or intended it to communicate something more significant about the narrative and the characters (which it does). Regardless, the underlying idea is change, forcing us to make one of three choices: we can change for the better, we can change for the worse, or we can resist change. Either way, character becomes destiny as we see in Lonesome Dove.

Newt and Lorena represent positive change. As Augustus put it: “It ain’t dying I’m talking about, it’s living.” Lorie, the young, beautiful whore, has one goal in life: to escape Lonesome Dove and escape to San Francisco. Former Texas Ranger and friend of Gus and Call, Jake Spoon gets her out of Lonesome Dove but abandons her on the trail. She tries to convince Gus to take her to California but Gus knows, “Life in San Francisco is still just life. If you want one thing too much it’s likely to be a disappointment. The healthy way is to learn to like the everyday things, like soft beds and buttermilk—and feisty gentlemen.”

San Francisco dreams are soon stripped away when Lorie is abducted by Blue Duck and abused by his gang. When Gus rescues her and takes her to Nebraska a new and better dream develops. There, in the home of Gus’s former love, Clara Allen, Lorie becomes content with a peaceful life on the Great Plains.

The orphan Newt’s dreams are more dusty. He longs to be accepted as a full-fledged hand in the Hat Creek outfit and to some day become a cowboy. When those hopes come true a new and more significant dream forms in his heart, especially after Gus tells him who his father is. Newt wants to be accepted by Call as his son. It’s a fool’s hope.

After arriving in Montana and surviving their first winter, with the coming spring Call has a last journey to make. Call puts Newt, now a confident young man, in charge of the ranch and gifts to him his prized horse, the Hell Bitch, his Henry Rifle, and his father’s pocket watch. Call doesn’t give Newt his name, however. Later, when confronted by Clara, she asks Call, “Does [Newt] know he’s your son?” Uncommitted, Call says, “I suppose he does—I give him my horse.” “Your horse but not your name?” “I put more value on the horse,” Call says and turns away.

Though Newt represents the greatest positive change in the novel, his last words are sad ones. The responsibility of the ranch and the gifts, even the gift of the Hell Bitch, is lost on him as to whether Call is his father or not. With a loneliness that lingers, Newt tells Pea Eye, “I ain’t kin to nobody in this world.”

Deets and Jake represent negative change. Again, as Gus put it: “Ride with an outlaw, die with [an outlaw].” The old proverbs fits here: “One bad apple spoils the whole bunch.” Or as the apostle Paul said, “Bad company corrupts good morals” (1 Corinthians 15:33).

These are true for Deets, the ever faithful companion and ever competent scout. He doesn’t cross the legal line as Jake does, but the upending of Deet’s life—of trailing cattle from his Texas home to faraway Montana—has tragic consequences. He seems to intuit he won’t survive the journey. He tells Call, “Don’t like this north. . . . The light’s too thin.” McMurtry then says, “Deets had a faraway look in his eyes . . . looking south, across the long miles they had come. . . . Call would catch him staring into the fire the way old animals stared before they died—as if looking across into the other place.” In the miniseries, Deets says to Augustus, “What are we doin’ up here, Captain? This ain’t our land. . . . A man ought not leave his land and his people.” Nor should a man be buried in foreign soil as Deets was.

Jake, whom Call says “just kind of drifts. Any wind can blow him,” fell in with a hard crew in Fort Worth after Lorena was abducted. He feigned a tough guy persona but soon realized he was overmatched in the toughness department by the Suggs brothers who kill cowboys and steal their horses, then murder two farmers, hang their corpses, and burn their bodies. It’s to Jake Gus says, “Ride with an outlaw, die with him. I admit it’s a harsh code. But you rode on the other side long enough to know how it works. I’m sorry you crossed the line.” And though Jake “liked a joke and didn’t like to work,” Gus and Call and the others hang their old compadre along side the Suggs brothers.

Gus and Call represent resistance to change. Gus is like the blue pigs he keeps and the sentiment painted on his sign: “We Don’t Rent Pigs.” Winston Churchill wrote, “Dogs look up to you, cats look down on you. Give me a pig! He looks you in the eye and treats you as an equal.” Augustus would agree with that. Horses and cattle, which the outfit sells, are the two animals, next to dogs and cats, that undergo the greatest change to their nature by living with people. As a result, their destinies are exclusively in the hands of humans. Not so pigs. Their destinies might be the same as cattle—the slaughterhouse—but pigs are always true to themselves. They’re independent critters. As such, there’s no sense in renting pigs, they’ll not do what you want them to do.

Such was Gus. Call would work from sunup to sundown. Not Gus. And no amount of coaxing from Call could change Gus’s basic nature. Even when he’s laying one-legged in Miles City, with blood poisoning in his other leg, Call fails to alter his friend’s stubbornness. When Call suggests removing the blackened leg Gus cocks his pistol and says, “You don’t boss me, Woodrow. I’m the one man you don’t boss.” Call says to him, “I never took you for a suicide, Gus. Men have gotten by without legs. . . . You don’t like to do nothing but sit on the porch and drink whisky anyway. It don’t takes legs to do that.” Gus is quick to respond: “I might want to kick a pig if one aggravates me.” Later, Gus says, “I’ve walked the earth in my pride all these years. If that’s lost, then let the rest be lost with it. There’s certain things my vanity won’t abide.” Pigheaded—and true to himself to the end.

For all of Gus’s stubbornness, it’s Call’s intractableness we remember about his character. It primarily revolves around his relationship with Newt. Call tells Dr. Mobley after Gus’s death, “I’m told I don’t have a human nature.” This is set in a stark light while Gus lays dying. “I told Newt you was his pa,” Gus tells Call. “Well, you oughtn’t to,” Call says. “I oughtn’t to have had to,” is Gus’s reply. He goes on: “You ought to do better by that boy. He’s the only son you’ll ever have—I’ll bet my wad on that. . . . Give him your name, and you’ll have a son you can be proud of. And Newt will know you’re his pa.” “I don’t know it myself,” Call says. “I know it and you know it,” Gus says with exasperation in his voice. “You’re worse than me. I’m stubborn about legs, but what about you?” The question is a haunting one. When Call gets back to the Hat Creek boys and has an opportunity to tell Newt, he couldn’t. “His own son stood there—surely, it was true; after doubting it for years, his own mind told him over and over that it was true—yet he couldn’t call him a son. His honesty was lost, had long been lost, and he only wanted to leave.” And so he did.

Call leaves his son in Montana and, as Augustus requested, takes Gus’s body back to Texas for burial. Gus considered his sign as his “masterpiece” and asked Call to “Stick it over my grave.” And so Call does—or at least the portion that survives: Uva uvam vivendo varia fit.*

A Note and Sources:

* The bottom plank containing the Latin motto appears in the miniseries. In the novel, the only board to survive is the top plank: “Hat Creek Cattle Company and Livery Emporium.” That’s what marks Augustus’s grave.

W. Gurney Benham, Putnam’s Complete Book of Quotations (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1926), 678b.

Benjamin Hufbauer, “Lonesome Dove: Uva uvam vivendo varia fit and Tragic Elements in a Western Epic,” in Sue Matheson, ed. The Good, the Bad and the Ancient: Essays on the Greco-Roman Influence in Westerns (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2022), 158.

Larry McMurtry, Lonesome Dove (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985), 77, 78, 80, 89, 330, 338, 548, 554, 600, 627, 760, 761, 763, 764–5, 768, 801, 809.

John Spong, A Book on the Making of Lonesome Dove (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012), 30.

Y’allogy: Texan Spoken Here.

To support Y’allogy please click the “Like” button, share articles, leave a comment, and pass on a good word to family and friends. The best support, however, is to become a paying subscriber.

Damned good writeup, Derrick! Makes me want to watch Lonesome Dove again. I haven't watched it in years.